The Prophetic Promise of the Land in the New Covenant

Dr. Randall Price

Pre-Trib Study Group Conference, December 1, 2013

Introduction

A critic of Israel once asked a Jew, “Why couldn’t you Jews just accept a country like Uganda? Why do you have to go back only to Israel? Equal to the question, the Jew replied, “Why do I go all the way across the country to see my grandmother, when there are plenty of old ladies nearby?” This rejoinder, in the style of rabbinic banter, reminds us that for the Jew, despite the cost and the controversy, there is no place in history to which he belongs except that one place that is his God-given earthy inheritance, the Land of Israel. This conviction, so unwelcomed by the politicians, has been a particular stumbling block for secularists:

What are we, finally, to make of this doctrine of The Land which gives theological significance—as it has been crudely put—“to a piece of real estate”? Many Jews, no less than Gentiles, have dismissed it as a bizarre and anachronistic superstition, unworthy of serious consideration. To many rationalists, and even humanists, especially since the Enlightenment, in a rational universe the doctrine is an affront. This response is generally coupled with the assumption that the doctrine is simply an aspect of that other doctrine of “choseness” or “election” that –so it is claimed—has irrationally and arrogantly afflicted (a verb chosen advisedly) the Jewish people, the particularism of The Land being, in fact, an especially primitive expression of the unacceptable particularism of the Jewish faith.”[1]

Yet, for the serious student of Scripture, the Land doctrine cannot be easily dismissed. It remains an undeniable fact of Holy Writ, a fact Old Testament theologian Walt Kaiser, Jr. reminds us of when he addresses this recognition within the Christian community:

Christian theologians are once again reclaiming the fact that “the land is central, if not the central theme of biblical faith,” and therefore, as W. D. Davies warned, “it will no longer do to talk about Yahweh and his people, but we must speak about Yahweh and his people and his land.” Likewise, Gehard von Rad summarized the situation by saying, “Of all the promises made to the patriarchs it was that of the land that was the most prominent and decisive.” In fact, few issues are as important as that of the promise of the land to the patriarchs and the nation of Israel: the Hebrew word ‘erets is the fourth most frequent substantive in the Hebrew Bible.[2]

These comments are generally accepted by both Jewish and Christian scholars as accurate with respect to the Old Testament or the Old Covenant. The Land of Israel was the stage for the great drama of salvation history and the Nation of Israel was at the center of this stage serving as the Chosen People for the LORD’s demonstration of His Presence and power in that history. However, everything changes when we move to the New Covenant, and for Christian scholars, to the New Testament. In the Old Testament, the language used for predicted events associated with the New Covenant, often within the same context as the language used to describe known historical events, is said to be hyperbolic or symbolic since the description portrays a surreal utopia for an Israel of the last days. In the New Testament, nothing like this is encountered, unless one includes the Apocalypse (which everyone knows is symbolic), and the New Covenant is seen as a distinctly Christian experience. The Old Covenant has been replaced by the New Covenant, Israel has been replaced by the Church, and the mission has moved from the limited territory of a place in the Middle East to the entire world. Reformed scholar O. Palmer Robertson says, “When the Christ actually came, the biblical perspective on the “land” experienced radical revision.”[3] Colin Chapman explains this revision as a result of a new Christocentric interpretation that he believes was taught by Jesus Himself:

Jesus seems to be silent about the subject of the land because for him the theme of the kingdom of God took the place of the theme of the land and everything else associated with it in the Old Testament. He used language from the Old Testament about the land, the ingathering of the exiles to the land and the redemption or restoration of the nation of Israel to describe his own ministry.”[4]

For those who have been taught to think that the final goal of the redemptive program is the Church and that all of the types and shadows of the Old Covenant were intended to yield this ideal, it is inherently wrong and patently absurd to not view everything under the New Covenant in terms of the church. Christ came to end the Old Covenant under which national Israel was the experiment, and the New Covenant and the Church is the final result. There is simply no possible concept of an Israel in the New Covenant that is not the Church. The primitive and earthly beginnings of ethnic distinctions and territorial boundaries have reached their ordained spiritual and heavenly goal in the Church. Its corporate unity can allow no ethnic distinctions (all its members are and only Christians) and its universal mission cannot be limited to a focus in the Middle East. Under this New Covenant, everyone is the chosen people and everywhere is the holy land.

Although an unbiased reading of the text would lead to a literal interpretation of a future kingdom for a spiritually restored Israel in the historical Land of Israel, no such unbiased reading is possible due to the constrains of hermeneutical approaches that have captivated and now control the thinking of the majority of contemporary scholarship and the pastors, teachers, apologists, and missionaries they educate in their classrooms and through their writings as well as all of the Christians under their influence who seek to understand the scriptures. This is also important for the reason offered by George Orwell in 1984: “Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.” Therefore, before coming to our own study, it is necessary to consider and critique the hermeneutical issues they put forth concerning the Land and the New Covenant.

Hermeneutical Issues Concerning the Land and the New Covenant

New Testament scholars and systematic theologians have the most trouble with the Land promises because they are not the focus of the New Testament and they tend to dismiss them as having any continuing significance in light of the New Covenant program they interpret as global and Christ-centered, not land-centered. However, since they recognize that the Old Testament is the foundation of the New, and the Scripture used by the founders of the Church, they must find a way to explain its New Covenant program that sees Israel’s restoration to the Land as essential the fulfillment. Old Testament scholars have a better understanding of these texts and also wrestle with how to reconcile them with the New Testament revelation. However, because of their academic training in higher criticism of the Bible and their need to conform to denominational creeds that are non-futurist, they typically view the prophetic texts as idyllic aspirations fulfilled historically under the Old Covenant or hyperbolic “restoration language” that was intended to find fulfillment in Christ and the Church. Consequently, the name given to their interpretive approach is the “New Covenant Perspective.”

The Literary Motivation Interpretation

Eugene March, Professor of Old Testament at the Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary, explains this perspective in contrast to the futurists school of interpretation:

The simplest version of the argument among Christians is that all the words of the prophets must be fulfilled because the prophets were predicting the future. Some prophecies have been fulfilled, but many have not. Among the latter is the prediction that at the end of time or at the beginning of the messianic age, the people of Israel—scattered abroad when their nation was destroyed as punishment from God—will be gathered and returned to their former land. Sometimes in this view, the return is seen as the beginning of a time when Jews will be converted to Christianity or at least will acknowledge that Jesus is the Messiah. For others, the ingathering of Jews is simply a sign of the end time, when Christians will be delivered from this evil world before final judgment falls on all nations.

On the surface, the argument is persuasive if the texts in question are read according to the presupposed theology. But a number of criticisms may rightly be lodged against this interpretation. First, the texts are taken out of their literary and historical contexts and understood as predictions, when in fact they were words of accusation and hope directed to particular audiences of real people. These were not mysterious words that would only be understood thousands of years after they were uttered. The whole notion is based on a misunderstanding of the character and intention of the biblical prophets and their work ...

Much more could be said in criticism of this position, which is vigorously advocated by some Christians known as “dispensationalists” and others known as “premillennialists” ... The fundamental error, however, is to read texts intended to engender hope and consolation too literally. The words were intended to assure God’s people of ongoing divine care and compassion. They may help us articulate a vision, but they do not constitute a deterministic program we can use to predict God’s time.”[5]

However, the literary contexts for these prophecies are concerned with desperate historical conditions (desecration, destruction and exile). Moderns can scarcely appreciate the degree of defilement the punishment of exile from the Land imposed on the Jewish People.[6] Could words designed to address such needs really engender hope and consolation if they could not be taken literally? The hope of the exilic and post-exilic communities was for a real restoration, whether in the near or far future. God’s promise for Israel’s future deliverance was often compared with His past deliverances (e.g., the exodus). If the Prophet’s audience interpreted divine intervention as real history, why should they not interpret the future promise of deliverance in the same manner? Hyperbolic rhetoric and literary devices may satisfy modern literary critics, but they did nothing for a people who needed to count on God for the future of their Nation. Can we seriously believe that the prophets’ (or worse, God’s) words to Israel never intended a historical fulfillment of restoration in the Land, but only a reassurance of the LORD’s care and compassion? If the promise was only meant to be words of encouragement, how was this encouragement to be realized? It could hardly have been realized in the 6th century B.C. return from exile since by the prophet’s own assessment this was disappointing on almost every level (nationally, politically, socially, and spiritually).[7]

The Cosmic Reinterpretation Interpretation

Others scholars who share a non-literal interpretation for these prophecies concede that the Prophets thought in literal terms, but that this was a misunderstanding later corrected by the New Testament’s transformation of the nationalistic concept of land to a cosmic scope under the New Covenant. This is explained by Lisa Loden, Director of Programs for the Caspari Center for Biblical and Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, when she asks:

How does this perspective affect an understanding of the return to the land described by Ezekiel and other prophets? In the nature of things Old Testament writers such as Ezekiel could only employ the images with which they and their hearers were familiar. In their case, the idea of restoration to the geographical land from which Israel had been deported represented the fulfillment of their fondest hopes. Yet in the context of the realities of the new covenant, this land must be understood in terms of the newly recreated cosmos about which the Apostle Paul speaks in Romans.”[8]

This viewpoint fails to observe that the Prophets also predicted the creation of a new heavens and earth (Isaiah 65:17; 66:22), but also, and like Paul, the deliverance from the curse imposed on the present earth (Zech. 14:11; Rom. 8:18-25). Hebrew University of Jerusalem Professor Moshe Greenberg makes the observation that a cosmic reinterpretation of the Old Testament hope in the Land cannot be maintained in light of the necessary bond of the Jewish People with the holy Land that defines them as a holy people:

Christians and Muslims, it is commonly said, differ from Jews in the nature of the holiness ascribed to the Land of Israel: the former have holy memories and holy places here, while for Jews the Land itself is holy. To Jews, every other land is an exile, but whatever happens here is significant, and the people living in the land are called to be a holy people. In general, human beings are not equally at home everywhere. To say that someone is equally at home everywhere is to say that he is not at home anywhere.”[9]

The consequence of such a view that forces a reinterpretation of the Old Testament, effectively nullifying its central promise of the Land to national Israel, is well stated by Menahem Benhayim, former Israel Secretary of the International Messianic Jewish Alliance of Israel of Israel:

In dealing with the theology of the Land in the context of Scripture, we must therefore not be tempted to do what the heretical Marcionites did—namely throwing out the earlier Scriptures as a relic from another ‘god’ and therefore quite irrelevant to Christians. Nor should we do what classical Christian theology has often done—namely transferring ‘Israel’ (the people and the Land) entirely to the spiritual realm. This may seem a more elegant way, but it still results in Israel being effectively irrelevant. (Unfortunately for such theology, the Jewish people and the biblical Land, have refused to accommodate to this scheme by becoming extinct or irrelevant.) Instead a realistic hermeneutic or ‘interpretation’ of the people and the land of Israel will relate, not just to the ‘extended’ meanings of Scripture, but also to its plain meaning.”[10]

Christological Transformation Interpretation

Another interpretive view, although one underlying all Christian non-literal views, is the position that the New Testament lens, which is focused on Christ, is the means to read and understand the Old Testament, which is focused on Israel and the Land. Representing this view as “the accepted and normative Christian interpretation,” religious ethicist Christopher Wright declares:

In New Testament theology the Christian Church, as the community of the Messiah, is the organic continuation of Israel. It is heir to the names and privileges of Israel, and therefore also falls under the same ethical responsibilities—though now transformed in Christ. Therefore the thrust of Old Testament social ethics, which in their own historical context were addressed to the redeemed community of God’s people, needs to be directed first of all at the equivalent community—the Church.”[11]

In response, it should be noted that the early Jewish Church did not possess this lens as they did not yet have a New Testament and nothing in the recorded teaching of Jesus, which was drawn from the Old Testament, offers a methodology for such a transformation. No where does Jesus declare that the Church will be the organic continuation of Israel, bear its titles and privileges, and fall under its ethical responsibilities. These were imbedded in the Mosaic Law that had been an exclusive conditional covenant with the Nation and which was largely rejected and replaced by throughout the history of the Church. Where then is this transformation except in the minds of those church fathers, who in seeking to distance themselves from the Jewish People who they regarded as apostate enemies to the Faith, sought to take their recorded blessings for themselves.

Present Fulfillment Interpretation

Swinging the hermeneutical pendulum the other direction, some in the Christian Zionist movement have attempted to find a literal fulfillment of this prophecy in the present-day events surrounding the formation of the modern State of Israel, finding the 1948 rebirth of the State fulfilling Isaiah 66:8, Israeli sovereignty over east Jerusalem in 1967 fulfilling Luke 21:24, and the reclamation of the Negev as fulfilling the blooming deserts of Isaiah 35:1 and 51:3. However, others in their own camp have countered that while such events may be significant in God’s preparation for future fulfillment,[12] they do not meet the conditions for present literal fulfillment:

From this perspective on Ezekiel’s prophecy, it would seem evident that the return of the Jews to the land in the twentieth century should not be regarded as a fulfillment of Ezekiel’s prophecy. Their re-formation as a state in 1948 involved no opening of graves, no resurrection of the body, no in-pouring of the Spirit of God, and no affirmation of Jesus Christ as the Lord of the covenant. However the restoration of the state of Israel may be viewed, it does not fulfill the expectation of Ezekiel as described in this most vivid prophecy. Instead, this picture of a people brought to newness of life by the Spirit of God naturally leads to a consideration of the role the land in the new covenant.”[13]

The gulf that divides the non-literal New Covenant perspective of the Reformed school and the literal futurist interpretation of the New Covenant in Dispensationalism is too wide for any hermeneutical bridge to cross. Reading the text christologically and transformationally so that every prophetic statement in the Old Testament about the Land is applied to the global mission of the Church is not spiritual, but anti-spiritual, for it robs God of the glory He has planned for Himself in history by a demonstration of His sovereign mercy in restoring national Israel (Ezek. 36:23, 36; Rom. 11:28-36). The New Covenant itself is stripped of its distinct features related to the Land, the allotment of Tribal inheritances, the Temple and the priesthood, and the witness of Israel to the nations of God’s reversal of Israel’s condition is nullified. How can these features be envisioned as even “spiritually fulfilled” by a marginal Jewish remnant within the predominately Gentile Church? However, the fact that God has preserved a remnant of national Israel in the Church according to His gracious choice is the present assurance of the fulfillment of His promised future work when the full number of the Gentiles has been added to the Church and the hardening of national Israel leads to national repentance and the full blessings of their New Covenant (Rom. 11:25-27).

Reasons Why the Land Must be Literally Restored to National Israel Under the New Covenant

In accordance with a dispensational hermeneutic that respects a consistent literal interpretation of prophecy within historic contexts, let us consider the historical and theological arguments for the necessary future restoration of national Israel to the Land under the New Covenant.

A. Historical Reasons

If literal fulfillment is expected of the New Covenant prophecies concerning Israel in the Land it is impossible to find precise fulfillment in any past possession, return or restoration experienced by the Nation. The primary texts related to this are at the time of the Conquest when Israel first possessed the Land promised to Abraham and the time of the return from the Babylonian exile.

Necessary to Realize Fully the Promised Boundaries of the Land

Despite the claim by the Reformed school that the full promise of the Land was fulfilled with the Conquest under Joshua (Josh. 21:43), National Israel never realized at any time in the past the possession and occupation of the entire Promised Land (Gen. 15:18-21; 17:8; Num. 34:1-15; Deut. 1:7-8). It is commonly argued that fulfillment came with the conquest of the Land under Joshua based on the statements in Joshua 21:43-45: “So the LORD gave Israel all the land which He had sworn to give to their fathers, and they possessed it and lived in it. And the LORD gave them rest on every side, according to all that He had sworn to their fathers, and no one of all their enemies stood before them; the LORD gave all their enemies into their hand. Not one of the good promises which the LORD had made to the house of Israel failed; all came to pass.” However, it is clear that much of the Land still remained to be possessed in Joshua’s day (13:1-6, 13) and even Jerusalem could not yet be totally possessed (15:63). Later statements in the book also state this fact (23:1-13; 24:1-28). But, though possession of the Land and rest was incomplete at that time, the Conquest had begun the process and this was assurance that God’s good word of promise to Abraham and his descendants would be fulfilled.

There was also a failure to possess the promised boundaries with the return of a Jewish remnant from Babylon to Judah in 538 B.C. First, a paltry return of less than 50,000 from one place, though noble and a evidence of faith in God’s promised deliverance through the Persians at the conclusion of the 70 year exile, cannot seriously merit the scale of regathering from the four points of the compass predicted for the new Covenant return (Isa. 11:12; 56:8; Ezek. 36:22; Zeph. 3:10; Zech. 8:7; 10:8-12). Second, “the enemies,” the “people of the land” (Samaritans) possessed the boundaries of Samaria (Ezra 4:2-5) and the Persians had hegemony over the entire country (Ezra 4:6, 12-13, 16, 20-22; 5:3). This was followed by a succession of foreign occupiers and rulers from the Greeks to the Romans, in fulfillment of Daniel’s vision of Gentile domination (Dan. 2:37-43) from the time of the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem until the advent of Messiah and the establishment of the messianic kingdom (Dan. 2:44-45; 7:13, 26-27; 8:19-25). The fulfillment of national Israel’s possession of the original boundaries promised to Abraham require Israel’s regaining independent rule over the entire country beyond what they have ever historically occupied (including the present modern State) since the country is free from enemies on every side and is paradoxically the head of all nations on earth.

Necessary to Realize the Full Promise of Rest in the Land (Deut.; Ezekiel 38)

The divine promise was also of “rest” in the Land. This “rest” was freedom from the threat of attack by enemies and translated to a security that permitted Israel to function offensively in its witness of holiness to the nations (Deut. 14:2), rather than defensively. Such uninterrupted rest in the Land was not realized at the time of Joshua’s Conquest since in the later time of David and Solomon the same claim is made to have given Israel another temporary rest from its enemies (2 Sam. 7:1, 11; 1 Kings 8:56; 1 Chron. 22:9).[14] The promise had been conditioned upon obedience to the covenant stipulations and this was repeatedly set before the people in Moses’ final instructions to the Nation (Deut. 4:40; 5:33; 6:18; 7:12-15; 8:6-10; et.al.). So long as it was possible for Israel to defile the Land by its sin (Ezekiel 36:22), divine discipline would use Gentile nations to threaten the Land and remove the condition of rest. Worse, judicial exile meant a postponement of rest until the people could return to the Land (the promised place of rest).

The return from exile, though a return to the Land, was not a return to rest in the Land. It has already been noted that foreign enemies had occupied parts of the Land during the time of the Babylonian Captivity, and that the entire boundaries of the Land were under the control of the Persian government. The efforts of Zerubbabel, Ezra, and Nehemiah were to afford some measure of rest (security) in Judah, but, this came at the cost of constant diligence and preparation to wage war (Neh. 4:11-20). This has continued to be the state of affairs for Israel during the times of the Gentiles until the present day.

Therefore, in order to fully fulfill this promised provision of the Land Covenant, it will be necessary for National Israel to live in the Land as a righteous Nation with no fear of future interruption of rest from its own actions or that of enemies. The New Covenant with national Israel promises such fulfillment. War will be abolished and all possibility of waging war removed (by the destruction of weapons of war), Isaiah 2:4. Israel will be unable to repeat its act of national disobedience because the entire Nation will experience spiritual regeneration and be enabled to fulfill their Chosen status as a holy people (Isa. 61:6; Jer. 31:33-34; 33:8; Ezek. 36:25-29a; 37:14). Moreover, there will be no enemies for Israel (Ezek. 39:26), for all of the nations that once threatened the capital of Jerusalem with war will now come to Jerusalem for worship (Isa. 2:3; 27:13; 60:3, 7, 14; 62:2, 7-9; 65:25; 66:18-22; Jer. 33:9-11, 16; Zech. 14:16). These conditions have no correspondence, even by analogy, in the Church Age, for under this phase of the New Covenant its people have reason to be disciplined (1 Pet. 4:15-17) and have enemies on every side (2 Cor. 12:10; Eph. 6:10-12; 1 Pet. 4:12-14; 5:8-10; 5:9), even from among the Jews (Rom. 11:28). For this reason, the next phase of the new Covenant will complete the promise with permanent, unhindered, and uninterrupted rest in the Land.

B. Theological Reasons

Since the New Covenant is one of the four unconditional covenants made by God with national Israel, it is necessary to set forth the arguments at this point why the New Covenant remains national Israel’s New Covenant and its promised fulfillment has not been transferred to the Church. The summary of these arguments has been well made by Arnold Fructenbaum:

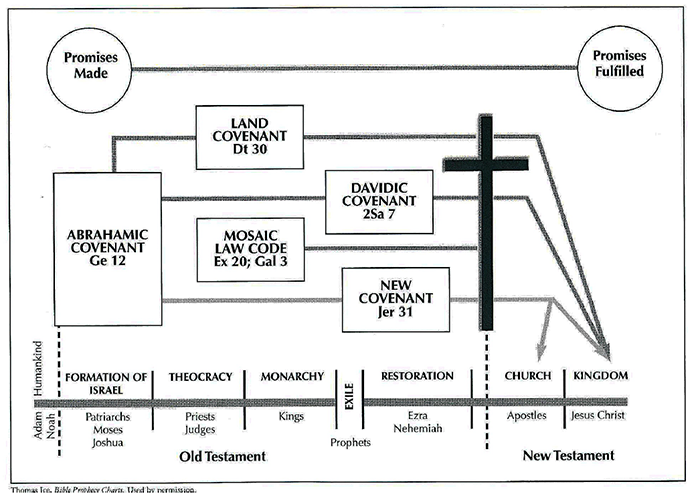

First, they are literal covenants and their contents must be interpreted literally as well. Second, the covenants God made with Israel are eternal and are not conditioned by time. Third, it is necessary to re-emphasize that these are unconditional covenants, which were not abrogated because of Israel's disobedience. Because these covenants are unconditional and totally dependent upon God for fulfillment, they can be expected to have an ultimate fulfillment. The fourth thing to note is that these covenants were made with a specific people: Israel. This is brought out by Paul in Romans 9:4: . . . who are Israelites; whose is the adoption, and the glory, and the covenants, and the giving of the law, and the service of God, and the promises ...This passage clearly points out that these covenants were made with the covenanted people and are Israel's possession. This is brought out again in Ephesians 2:11-12: Wherefore remember, that once ye, the Gentiles in the flesh, who are called Uncircumcision by that which is called Circumcision, in the flesh, made by hands; that ye were at that time separate from Christ, alienated from the commonwealth of Israel, and strangers from the covenants of the promise, having no hope and without God in the world. The four unconditional covenants belong to the people of Israel and, as this passage notes, Gentiles were considered strangers from the covenants. Fifth, while a covenant is made at a specific point of time, not all of the provisions go immediately into effect. At the time a covenant is signed or sealed, three things happen: some do go immediately into effect; some go into effect in the near future; and some go into effect only in the distant or prophetic future.[15]

With an understanding of the continuing active status of the New Covenant as national Israel’s promised covenant, we may consider some of the theological reasons why it is necessary for national Israel, not the Church, to fulfill the New Covenant only in the Land, not throughout the world, as this covenant stipulates.

Necessary for Theocratic Theodicy (Vindication of God’s Sovereignty over the Land)

The shameful situation of national Israel as rejected by God and scattered among the nations requires an ultimate explanation. For the Jewish People, enduring savagery, despoilment, and worse: forced defilement in foreign lands through persecution, pogrom, and holocaust, one answer to their suffering has been the fact that they were “Chosen.” This, of course, has only strengthened the feeling that something is not right with God. Another answer might be that they agreed to a covenant and failing to obey its stipulations received what they deserved. However, if God chose them and made unconditional promises to them for blessing and prosperity in the Land, how can He be vindicated in light of the reality that most of their existence has been outside of the Land? The Prophets especially focused on this problem because their prophetic messages dealt in large measure with the historical contexts of the Assyrian deportation of Israel and the Babylonian destruction of Judah and Jerusalem and the exile of the people.[16]

The answer given by the Prophets was theocratic theodicy[17] under the New Covenant. A proleptic preview of this has been demonstrated with a remnant of national Israel and a remnant of the Gentile nations in the Church.

The relationship of the Jewish and Gentile remnants as part of the “all Israel” (Rom. 11:26) and “all the families of the earth” (Gen. 12:3) is explained as a necessary (though unexpected) part of the divine program in Acts 15:16-18 based in part on the prophecy of Amos 9:11. It was already understood that Messiah would not return and bring the promised restoration until national Israel repented (Acts 3:19-21). Now, it is understood that Messiah will not return until “after” (vs. 16) the remnant of Gentiles (“the full number,” Rom. 11:25) have been brought to faith. For that reason national Israel has been partially and temporarily hardened and experienced rejection that the Gentiles might be included in the program of salvation (Rom. 11:11-15, 25).[18] Therefore the normative situation for the Church Age will be national Israel in a hardened condition (Acts 28:25-27; Rom. 11:25; cf. Jn. 12:37-40 based on Isa. 6:9-13), a remnant of Israel saved (Acts 28:24; Rom. 11:5; cf. Jn. 12:42), and a remnant of the Gentiles saved (Acts 28:28). During Israel’s time in the Land a remnant of national Israelites had salvific priority and comparatively few Gentiles were saved and brought into national Israel. During the Church Age this is reversed, with salvific priority extended to the Gentiles and comparatively few Jews saved and brought into the Church. However, Gentile inclusion serves a greater purpose in the divine plan in provoking national Israel to jealousy and thereby causing them to seek this salvation first extended to them (Rom. 11:11, 14; cf. Acts 15:11). Therefore, Gentile conversion during the present Intercalation helps prepare national Israel (and the Gentile nations) for the greater inclusion under the future New Covenant. Salvation has been recognized as a key element of the coming Kingdom by as diverse theologians as Ladd: “The Kingdom of God stands as a comprehensive term for all that the messianic salvation included”[19] and Kaiser: “The kingdom of God is both a soteriological as well as an eschatological concept.”[20]

The spiritual inclusion in the present era will find the addition of the national and physical inclusion in the future era. However, this mediatorial role performed by the remnant of the nations during the Church Age, within the period of Gentile dominion over national Israel, will be reversed in the Mediatorial Kingdom, with national Israel having the dominion and serving in a mediatorial role for the nations. Those that were formerly excluded are now included as the times of the Gentiles give way to the time of Israel’s restoration. Though not as clear, it appears that the transitional period during the Tribulation that prepares Israel and the nations for the messianic advent and the Millennial government will see a partial experience of the coming mediatorial role for Israel as the Gentile nations are judged with respect to their relationship during this time with the believing remnant of national Israel (Matt. 25:32-46), see chart below:

Israel and the Land Under the New Covenant

| Times of the Gentiles | Time of Israel's Restoration | ||

| Church Age | Tribulation | Millennium | |

| National Israel | Presently excluded Remnant included |

Provisionally included via Remnant of national Israel (Jer. 30:7b; Zech. 12:10–13:1) |

Included (as head) Deut. 28:13; Isa. 12:6; 60:14–16; 62:2 |

| Gentile nations | Presently excluded Remnant included |

Provisionally included via Remnant of national Israel (Matt. 25:32–46) |

Included (as tail) Isa. 2:3; 60:10–12; Zech. 8:23 |

| Land | Under divine discipline (Daniel 8:19; Luke 21:24) |

Under divine wrath (Rev. 6–19) |

Restored and Renewed (Isa. 27:6; 60:21; 62:4; Ezek. 36:34–36) |

While only the spiritual provisions of the Abrahamic Covenant have been enjoyed in implementation of the New Covenant since Pentecost, the full provisions of all of the biblical covenants will be experienced by national Israel and mediated to the nations in the Millennial Kingdom. The vindication of God’s relationship with national Israel and the Land will require a reversal of their ritually defiled status caused by Israel’s sin that polluted the Land and the negative witness in their being exiled from the Land and the Land becoming unclean due to both Israel’s idolatry and the presence of foreign occupation that furthered the idolatrous contamination.

Reversal of Ritual Defilement in the Land (Ezekiel 36:21-22, 36-38; 37:25-26)

The status of the Land as holy and the fact that it could be de-sanctified by the actions of the nation of Israel and the resultant discipline from foreign invasion threatened the recognition of God’s theocratic status. For example, Jeremiah records God’s verdict concerning Judah’s actions: “And I brought you into the fruitful land, To eat its fruit and its good things. But you came and defiled My land, And My inheritance you made an abomination” (Jeremiah 2:7). Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion (New York) Professor of Bible Harry Orlinsky, explains the reason this relationship between God and the Land:

There is the aspect of holiness that was associated in the Bible with the Land, and the exclusive status of Jerusalem as the only Holy City—a status that Jerusalem never lost among the Jewish people ... To the biblical writers, the holiness of the Land derived immediately and directly from the holiness of God Himself, that is to say, God is holy and His presence [kavod, “glory”] and abode are holy, and they generate holiness; and so the Land (as His people) is holy and must be maintained unmarred and undefiled by wrongdoing.”[21]

The Prophet Ezekiel makes this clear when he records the LORD’s own explanation of the theological dilemma created by national Israel’s violations of the covenants: “But I had concern for My holy name, which the house of Israel had profaned among the nations where they went. “Therefore, say to the house of Israel, ‘Thus says the Lord GOD, “It is not for your sake, O house of Israel, that I am about to act, but for My holy name, which you have profaned among the nations where you went. “And I will vindicate the holiness of My great name which has been profaned among the nations, which you have profaned in their midst. Then the nations will know that I am the LORD,” declares the Lord GOD, “when I prove Myself holy among you in their sight” (Ezekiel 36:21–24).

National Israel’s actions required divine discipline in accordance with the stipulated covenantal punishment of exile (Lev. 26:23-25, 31-33; Deut. 3:25-27; 2 Chr. 36:16-17; Jer. 5:14-15; et. al.). Yet this necessary judicial action allowed the nations to falsely assume that God was like their local deities. The conquest of his land and the exile of his people implied he was powerless to prevent either. Habel links the LORD’s rule over the Land with the demonstration of His sovereignty, noting:

“The allocation of a piece of YHWH’s universal domain to Israel and the establishment of Israel as a people in that land are crucial steps in the public demonstration of YHWH’s sovereignty over all lands. In Deuteronomy, the text presents YHWH as a deity seeking to prove these claims to universal dominion.”[22]

On the day that the LORD restores the Land to national Israel He will, in the Land, effect ritual purification for the Nation to reverse their unclean condition so both He and they may dwell in holiness in the Holy Land.[23]

The review of Israel’s sinful history in Ezekiel 36:16-17 is brief and to the point: “when Israel was living on their own Land, they defiled it by their ways and their deeds” (vs. 17a). The purpose of this summary is to exonerate God for the judgment of exile, but also to demonstrate that the ground for national Israel’s salvation and restoration can only be based on God’s sovereign grace. Verse 17 to reveals the condition of the people is “defilement” (Hebrew tame’).[24] Verses 18-21 explain that the nation had specifically defiled the Land by idolatry (verse 18).[25] As a result, “the Land became defiled and God punished it and it expelled its its inhabitants” (cf. Leviticus 18:25). Israel’s unholy character caused it to be removed from the "holy" land. This retributive judgment broke the covenantal triad that existed between God, the people, and the land, and resulted in the profanation of the Lord’s Holy Name by the nations (vss. 20-21), a situation requiring both restoration (for Israel and the Land) and vindication (for the LORD). This will be achieved in a reversal of the condition, emphasized in the original text by opposing synonyms of exile that correspond in thought and rhyme to the wording used for the promise of return and restoration in verses 19 and 24. This correspondence reveals the divine intervention that characterizes the restoration of Israel under the New Covenant in vss. 25-28:

I scattered them among the nations (19a), I will take you from the nations (24a)

I dispersed them among the lands (19b), I will gather you from all the lands (24b)

From Israel’s perspective, the exile threatened the prophetic fulfillment of the historical covenants that depend on Israel’s possession of the Land. From the divine perspective, the necessity of divine judgment by exile resulted in God’s holy Name being profaned by Israel in the midst of the nations by which and to which the Nation was exiled (verses 20-21). Israel’s exile made the nations think Israel’s God was impotent resulting in a "profanation" of God’s holy Name. The seriousness of this offense can be seen in the meaning of the verb “profane” (Hebrew chalal), which means, "to pollute, defile, profane, violate, desecrate, make common."[26] In the ancient Near East the fortunes of a nation and its deity were inseparable and the relationship between a god, a people, and a land was intimate. A god who did not vindicate himself in the arena of history was no god at all. Israel’s exile had made the nations view Israel’s God as only a local deity that could be derided just as his people. W. F. Lofthouse explained this problem by noting that "sin is not only evil in itself, but it compels God to do what men are bound to misunderstand."[27] The exile was interpreted by the nations as stemming from God’s impotence, inferiority, inability, abandonment, or unfaithfulness to protect His people and Land. Therefore, instead of Israel's history moving towards the prophetic goal of the nations’ recognition of Israel’s Sovereign LORD, the exile had taken matters in the opposite direction and ruined Israel, and especially God’s, reputation among the nations.

Before the restoration of national Israel can be accomplished (verses 33-38) the problem of divine profanation must be resolved through divine sanctification (verses 22-23) by bringing national Israel under the New Covenant (verses 24-32). This will reverse the nation’s opinion about the nature of Israel’s God through the worldwide regathering and unparalleled restoration of Israel and the Land. Anything less would only confirm Israel’s God as a powerful local deity, but that He must be acknowledged by the nations as the only and true Sovereign (verse 23b). This requires a supernatural restoration physically and spiritually, which is initiated by a return to Israel’s “own Land” (verse 24). This confirms that there can be no fulfillment of any of the prophetic promises of the past unless Israel is restored to her Promised Land. The next verses (25-27) describing Israel’s national regeneration and restoration under the New Covenant, reveals that this spiritual fulfillment cannot take place apart from the physical return to the Land. Likewise, the inward renewal of the people in these verses results in outward renewal of the Land of Israel (verses 29-30).

It is also important to remember that the New Covenant was to be made with “the house of Israel and the house of Judah” (Jeremiah 31:31) not with the Church. While the Church partakes of the spiritual blessings of this covenant through the Gentile inclusion made that “all of the families of the earth” would be blessed “in Israel” (Genesis 12:3; cf. Amos 9:11-12; Acts 15:16-18) only Israel possesses the covenant and fulfills it. For this reason, the experience of the indwelling Spirit in the Church Age (Acts 2:4; 15:8-9) is not a replacement of Israel by the Church, but the token of promise made to the Jewish Remnant within the Church (Romans 11:1-5) alongside Gentiles who are in Israel’s Messiah (and therefore share the spiritual aspects of the Abrahamic Covenant, Romans 4:16; 11:17-18; Galatians 3:7-9, 29) and the foreshadowing of both national Israel’s and the nations’ universal experience under the New Covenant in the Millennial Kingdom (Joel 2:28-32; cf. Psalm 22:27; Isaiah 11:9b/Habakkuk 2:14).

The restoration of Israel takes place in stages, with an initial regathering from the nations and a return to the Land of Israel as the first stage (vs. 24), followed in verses 25-27 by a second stage. The first stage is physical: restoration to the Land, the second stage is spiritual: restoration to the Lord. These stages can again be distinguished in the next chapter in the process of restoration in the vision of the dry bones (37:1-14) and the reuniting of the Nation (37:15-28). This fulfillment can take place progressively through time with national spiritual regeneration (verses 25-27) and repentance (verse 31) taking place at the end of the Tribulation (cf. Rom. 11:25-27), which will result in the full and final regathering of Israel into the Land for the Millennial Kingdom (Matthew 24:31/Mark 13:27).[28]

The spiritual regeneration of Israel as the second stage of restoration is seen in verses 25-27. Pure water is sprinkled upon national Israel ritual cleansing at the start of the New Covenant so that they may “live in the Land I gave to your forefathers” (vs. 28). The nature of this spiritual renewal is both individual and national, as it is both cleansing from ceremonial defilement and a purging from idolatry.[29] To accomplish such a national purification requires a forensic act (implied by the use of the verb tahar in the Piel perfect), which means, "to declare ceremonially clean." This creation of Israel as a ceremonially clean community is part of the vindication of God’s holy Name since this condition is necessary for the restoration of the Lord’s Presence to Israel. However, restoration to a state of ritual purity does not guarantee the maintenance of this condition, so an individual spiritual regeneration will be necessary to preserve the restoration in perpetuity. Verses 26-27 describe this spiritual regeneration as a radical change in the inner disposition by the removal of that which caused ritual defilement and the implantation of a new nature.[30] The theological expression of “new” (“new heart” and “new spirit”) is one of the more recognizable spiritual blessings of the New Covenant (Jer. 31:33-34), chiefly because it is the blessing that has been available to the Church in this dispensation (Jn. 3:5-7; Tit. 3:5-6). The remainder of verse 26 reveals the change in national Israel from a hardened condition ("the heart of stone") to one that is receptive to Messiah ("a heart of flesh”).[31]

This language symbolizes Israel’s national repentance (Zech. 12:10-13:1; Rom. 11:25-26) and the bestowal of a new nature will qualifies the renewed Nation to live under the New Covenant. In addition, God’s own [Holy] Spirit indwells the Nation individually and corporately (as it does the Church today) so that Israel will be enabled to live under the New Covenant (vs. 27b) and so that no future reversal of fortune will occur because of repeated acts of defilement.[32] This new condition insures Israel’s permanent residence in the Land and guarantee that God’s Name will never again be profaned among the nations. This blessing of the New Covenant results in a re-establishment of Israel in its ancestral Land (vs. 28), fulfilling the promise in the Abrahamic Covenant that the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob would possess the Land “forever” as an “everlasting possession” (Genesis 13:15; 17:8; 48:4; Joshua 14:9; 1 Chronicles 28:8; 2 Chronicles 20:7; Psalm 37:29; Isaiah 37:14; 60:21; Jeremiah 7:7; 25:5). The verse closes with the covenant-oath formula (first stated in complete form in Leviticus 26:12): “you will be My people and I will be your God.” This oath throughout the Old Testament defines and describes a relationship of obedience and fidelity between God and His people and is figuratively a type of wedding metaphor depicting the intimacy of the relationship promised for the New Covenant (Isa. 62:4).

With the physical implementation of the blessings of the New Covenant the establishment of National Israel in the Land demonstrates the LORD’s universal sovereignty, not because the Land of Israel is part of the earth, but because gaining dominion over this place at the center of Satanic control through the Antichrist and the world’s armies, demonstrates His putting down universal opposition (Rev. 19:20-20:2-3). For this reason Psalm 2:6 and Zechariah 14:9 conclude their depiction of the final battle with King Messiah as the universal sovereign. However, the reason the Land is at the center of this end time drama is because in the divine program it was destined to be the throne of Messiah and the focal point of divine rule over the earth (Rev. 21:24).

Necessary to Fulfill the Messianic Program (Rule as King in Zion)

While there is continuity between NC1 and NC2 because of the shared spiritual blessings by the remnants of Jews and Gentiles in the Church, when it comes to the issue of direct Messianic rule there is significant discontinuity (as the chart below illustrates):

Discontinuity in the Church and Israel in the New Covenant

| New Covenant (NC1) | New Covenant (NC2) |

| Church participates | National Israel fulfills |

| National Israel rejects Messiah | National Israel accepts Messiah |

| Remnant of national Israel receives partial blessings | Remnant of national Israel receives promised blessings |

| Gentile remnant included in partial blessings of New Covenant | National Israel mediates to Gentiles full blessings of New Covenant |

| Land under divine discipline | Land under divine blessing |

| Part of national Israel outside land | All of national Israel in the land |

| Partial possession of partial land | Full possession of Promised Land |

| Spiritual temple and spiritual priesthood | Functioning temple and Levitical priesthood |

| Spiritual temple indwelt by Messiah | Physical temple is throne of Messiah |

| Provisional atonement by spiritual confession | Provisional atonement by ritual sacrifice |

| God's name profaned by the nations | God's name glorified by the nations |

From the above chart it can be seen that national Israel’s position in the Church Age (NC1) is rejected because of their rejection of Messiah while in the Kingdom (NC2) national Israel is accepted because it has accepted its Messiah. This discontinuity makes it impossible for the promised New Covenant blessings related to the Land, the Temple and priesthood (Jer. 33:17-26), and the Davidic rule to find literal fulfillment during the Church Age. It is beyond the scope of this paper to engage the New Covenant Perspective (shared in part by Progressive Dispensationalism) that Christ’s session as Lord in heaven has fulfilled the promise of a seed of David (2 Sam. 7:16; Ps. 89:35-36) ruling Israel (Acts 2:30-36). However, it should be evident, as David Olander has stated, “to depart from this promise of the Davidic covenant in any way is to depart from the defined covenanted kingdom program God has established. God had made it very clear to David that his seed זַרְעֲךָ֙ (literally your seed masc. sing.) would be heir to the throne and kingdom (2 Sam. 7:12-13).”[33] The throne of David (and his descendants) is on earth and in Israel and therefore this can only be fulfilled literally by the Davidic Messiah physically returning to the Land of Israel and ruling over the Nation. Under the New Covenant this rule will be universal, but it will still be from a fixed point, a throne in Israel (“My kingdom”) and within the Temple (“My house”), 1 Chr. 17:11-14. The Land under the New Covenant becomes the place of the Messianic government centered in Jerusalem (Jer. 3:17), to which all of the nations come to bring their wealth in tribute to the LORD at the Temple (Isa. 60:5-7, 10-14; Rev. 21:24). This is affirmed with respect to the Messianic rule in Psalm 2:6: “But as for Me, I have installed My King Upon Zion, My holy mountain.”

Necessary to Fulfill the Explicit Provisions of the Unconditional Covenants

Under the New Covenant the provisions of the unconditional covenants will find fulfillment once and for all (see chart below). For this reason Isaiah declares, “Then all your people will be righteous; They will possess the land forever, the branch of My planting, the work of My hands, that I may be glorified” (Isaiah 60:21). The provisions in these covenants are all Land-based and

therefore first require national Israel’s regathering, return and restoration in the Land in order for fulfillment to take place. Even those non-Land-based provisions, such as spiritual regeneration, are to be enacted for the nation after it has been brought back to the Land. The nature of Israel’s New Covenant (see chart below) completes the national promises made in the Abrahamic, Land, and Davidic covenants that could not be fulfilled in Israel’s past history due to covenant violations and divine judgment (exile).

| The Nature of Israel’s New Covenant “Behold, the days are coming, says the LORD, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah ...” Jer. 31:31 “I will not treat the remnant of this people as in the former days ...” Zech. 8:11 |

|

| National Israel regathered to land | Isa. 11:11–12; Ezek. 36:24; 37:21, 25; Matt 24:31 |

| Nation and land boundaries increased | Isa. 26:15; Ezek. 36:37–38; 47:13–48:34 |

| Twelve tribes reunited as one nation | Isa. 66:8; Ezek. 37:19–22 |

| Rule by King Messiah (Davidic reign) | Jer. 23:5–6; 33:17; Ezek. 37:22a, 24; Zech. 9:10; 14:9 |

| Idolatry, transgression, defilements removed | Ezek. 36:25; 37:23 |

| National Israel spiritually regenerate | Jer. 31:33–34; Ezek. 36:26–27; 37:14 |

| No war, covenant of peace | Isa. 2:4; Ezek. 37:26; Zech. 9:10 |

| Curse removed | Zech. 14:11 |

| Renewal of nature and harmony within creation | Isa. 11:6–9; 27:6; 65:20–25; Zech. 8:12; Rom. 8:21 |

| Israel recognized by nations as blessed | Isa. 62:2; 66:18; Ezek. 36:23, 36; 37:38; Mal. 3:12 |

| Jerusalem re-sanctified, center of Earth | Isa. 2:3; 4:3–6; 65:18; Jer. 3:17; 33:9, 16; Zech. 8:3–8 |

| Nations subservient to national Israel | Isa. 49:7; 60:5, 10, 12–16; 61:6; Zech. 8:22-23; Micah 4:2 |

| Temple rebuilt and indwelt by Divine presence | Isa. 2:2; 56:6; Ezek. 37:26–28; 40–48; 43:1–7; 48:35 |

| Levitical priesthood and sacrificial system restored | Isa. 60:7; 66:20–21; Jer. 33:18, 22; Ezek. 44–45 |

| Eternal (five-fold repetition of “forever”) | Isa. 24:5; 61:8; Jer. 31:36, 40; 32:40; 50:5 |

The Land under the New Covenant becomes the place in which the divine drama comes to completion, including the end time Satanic assault on Jerusalem and final divine deliverance (Rev. 20:7-10). For this reason Lawrence Hoffman can say:

Throughout, he presents the Land as not simply one central idea among many that the Bible offers us, but another facet of the primary motif without which, he says, the entire biblical corpus cannot be comprehended accurately: “the Land as covenant” itself.][34]

The Restoration of the Land under the New Covenant

In the remaining chapters of Ezekiel’s vision (47:1-48:35) the restoration of the Land in the under the New Covenant is given center stage. Topographical changes will have created the mountain of the house of the Lord with its sacred district and holy portion containing the Millennial Temple. From beneath the Temple there will spring forth a renewing river that transforms the formerly barren and unfruitful lands of the Judean lowlands and the Dead Sea region (47:1-12).[35] Briefer accounts of this prophetic event were made before Ezekiel’s time by Joel (3:18) and after by Zechariah (14:8). The changes effected by this river of life, which produces “all kinds of trees” growing on each side of the Dead Sea, whose “fruit is for food and leaves for healing” serve as a constant witness throughout the Millennium to both national Israel and the nations that the New Covenant is a continual source of restoration blessing for the Land, as Isaiah’s prophecy had stated: “In the days to come Jacob will take root, Israel will blossom and sprout; and they will fill the whole world with fruit” (Isaiah 27:6).

As an interesting aside, Tom Meyer sought to see if the sites given in Ezekiel’s “prophetic geography” could be located within the modern Land. He found that if he measured between these sites using the royal cubit the first station is directly across from the Eastern Gate in the Kidron, the next station 1,000 cubits distant is exactly at the Gihon Spring, the next station another 1,000 cubits away is exactly at the junction of the Kidron and Ghenna, the next is exactly at the Kidron and Wadi Yasoul (sometimes called Wadi Azal (Zechariah 14:5) in the Silwan Village, and the final station is at the intersection of the Kidron and the first view of the southern end of the Mt. of Olives. At every station there is a natural intersection of the wadis with the river coming from the Temple, hence the increase in water level (Joel 3:18) flowing to the Dead Sea (47:10).[36] If correct, this provides additional evidence that the “prophetic geography” is to be literally fulfilled in the same place (today the modern State of Israel).

The Distribution of Land under the New Covenant (Ezekiel 47:13-23)

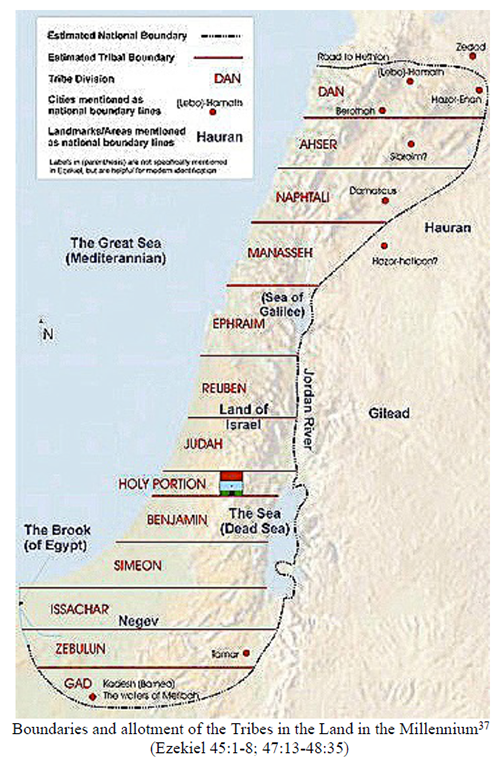

Under the New Covenant the Land will be distributed into twelve tribal divisions (verses 13-14). God had sworn, i.e., promised by oath (Ezekiel 20:5, 15, 23, 42; 36:7; 44:12; cf. Exodus 6:8; Nehemiah 9:15; Psalm 106:26) to Israel’s forefathers the Land as “an inheritance” (verse 14), which was, as in the past, a defining feature of His covenant with His people (Deuteronomy 32:9). Therefore the historical covenants (Abrahamic, Land, and Davidic) all preserved this unconditional promise of the Land, not simply as a place of occupation, but as an inheritance (something passed on within the tribe to their descendants). Even though the tribal divisions were allocated, the promised boundaries given to Abraham (Genesis 15:18-21) and reconfirmed to Moses (Numbers 34:1-12) never were completely realized. This time of fulfillment awaited the New Covenant (Ezek. 37:25). That the fulfillment is in this eschatological period can be seen from the fact that the tribal divisions in Ezekiel are different from that in the past (Joshua 11:23; 13:7-33; 14:1-19:51; 22:1-34; 23:4; cf. Judges 18:1-31), although the boundaries of the Millennial Land of Israel (47:15-20) generally follow the boundaries as originally given in the Abrahamic Covenant (see map below).

The Land delineated by these boundaries[38] will be distributed to the twelve tribes for their inheritance (Ezek. 48:21) but also for the alien (non-Israelite) who desires to settle permanently and have children in the Land. Under the Mosaic Law resident aliens were to be protected and allowed specific privileges among the native Israelites (cf. Leviticus 19:33-36; 24:22; Numbers 15:29; Deuteronomy 14:29; 26:11) based on the fact that Israel had also once been strangers in a strange land (Egypt). However, this depended on the alien submitting to the Law, since was to be “one [the same] statute for the Israelite and alien” (Deuteronomy 10:18-19; 21:12-13; 24:17; 27:19). This required resident aliens to have proselyte status (cf. Exodus 12:19; 16:29; Leviticus 17:12, 15; 18:26; Numbers 9:14; 15:15-16; Ruth 1:16-17). Moreover, they were excluded from having any inheritance among the sons of Israel (Numbers 26:53-55). By contrast, in the Land under the New Covenant national Israel will treat resident aliens like those born in the Land allot them an inheritance among the twelve tribes (Ezek. 48:22-23). Moreover, there is no longer a condition of proselytism, since under the New Covenant Jews and Gentiles alike will begin the Millennium as believers indwelt by the Spirit.[39] Only under the New Covenant, when restoration conditions have been attained, universal peace has been attained, a national regeneration has occurred, the promised boundaries achieved, and the tribes can again be identified and allotted their inheritance, can Israel be expected to fulfill the responsibility toward residents from the nations.

The Division of the Land under the New Covenant (48:1-35)

The twelve tribes of Israel, having been regathered, re-identified, reunited, and restored to the Lord and to the Land will be re-distributed by tribes within the boundaries of the Land. The seven northern tribes will be separated from the five southern tribes by the holy portion upon the Millennial mountain which contains the city of Jerusalem and the Temple.[40]

This holy portion (verses 12-15) contains the Millennial Jerusalem in the southern division that will be laid out as a square of 4,500 cubits (7,875 feet) covering an area of 2.2 square miles (verse 16). The Millennial Jerusalem will have lands around it under the control of workers (who live in Jerusalem but who come from all of the tribes), which is designated for agricultural purposes in order to feed the working population (verses 18-19). This description of cultivation, production and consumption (cf. 36:9-11, 29-30, 34-36; 47:12) indicates that this is very much an earthly reality. The pietistic and allegorical mindset of the church fathers (most famously in Augustine) could not the concept of a literal Millennial Kingdom (Revelation 20:6) and cited against this Paul’s words in Romans 14:17: “for the kingdom of God is not eating and drinking, but righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy Spirit.” However, under the New Covenant where the curse has been removed, there is nothing carnal in this necessary activity, but its Land-based character counters the symbolic school’s attempt to harmonize it with the heavenly New Jerusalem.

The Land-based Role of the Levitical Priesthood

Under Israel New Covenant, the Levitical priesthood and the sacrificial system will be renewed to function at the Messianic Temple and to reside in the Priest’s Portion in the Land (Ezek. 48:9-14). Jeremiah 33:18 announces the permanency of this New Covenant priesthood and sacrificial system: “and the Levitical priests shall never lack a man before Me to offer burnt offerings, to burn grain offerings, and to prepare sacrifices continually.” Other prophetic texts provide details of both the priestly duties and of the various sacrifices and of the atonement they render for the Temple furniture (Ezek. 43:20, 26) and for national Israel (Ezek. 45:15, 17, 20) and probably for the Gentile nations who come to Jerusalem to learn the ways of the LORD (Isa. 2:3) or make an annual ascent to Jerusalem to worship the LORD at the Millennial Temple, (possibly through a present offerings on behalf of their national entities) and to celebrate the Feast of Booths (Zech. 14:16-19). Isaiah 66:19-21 predicts that the priests and Levites will not only come from the tribe of Levi as required under the Mosaic Covenant, but also from believing Jews who were left in distant Gentile nations (vs. 19).[41] Priestly emissaries from the Land will form an envoy and transport them to “My holy mountain Jerusalem” (vs. 20) where those selected for priestly service will apparently be trained in the sacrificial system (vs. 21).[42] In addition, a choice piece of the Land will be designated as an holy allotment for the Zadokite priests who historically did not go astray as did the the Levites (Ezekiel 48:9–14).

The Land-based Mediatoral Blessings to the Gentile Nations

Under the New Covenant the blessings received by national Israel will be mediated to the Gentile nations (Isa. 2:3; Zech. 8:21-23, et. al). As a result the nations will gladly serve in the rebuilding of the Temple and resettlement of Israel in the Land. This is best exemplified in Isaiah 60:10-13: “The glory of Lebanon will come to you, The juniper, the box tree, and the cypress together, To beautify the place of My sanctuary; And I shall make the place of My feet glorious. “And the sons of those who afflicted you will come bowing to you, And all those who despised you will bow themselves at the soles of your feet; And they will call you the city of the LORD, The Zion of the Holy One of Israel. “Whereas you have been forsaken and hated With no one passing through, I will make you an everlasting pride, A joy from generation to generation. “You will also suck the milk of nations, And will suck the breast of kings; Then you will know that I, the LORD, am your Savior, And your Redeemer, the Mighty One of Jacob.”

Biblical Texts Affirming the Prophetic Promise of the Land in the New Covenant

The scope of this study cannot deal with the extensive Old Testament texts that treat the fulfillment of national Israel’s new Covenant. However, selected texts from this corpus will be considered, while concentrating on the New Testament where references and allusions to the Land under the New Covenant are few and more stringently debated.

Old Testament Texts Affirming the Prophetic Promise of the Land in the New Covenant

When we follow the history of Christian interpretation to those Old Testament texts and contexts treating the subject of the New Covenant we come to a long deserted field where the weeds of misunderstanding have grown tall for many centuries of the professing Christian Church. W.D. Davis, who has helped cultivate this crop, notes this history saying,

Beginning with the New Testament, and certainly since St. Augustine, Christianity in its major expressions has substituted for the holiness of place—The Land, Jerusalem, the Temple—the holiness of Christ. The Land—although called Holy in Christianity—is ultimately incidental in Christian affection and faith. Life “in Christ” replaces life “in The Land” as the highest blessing, so that the traditional Jewish doctrine of the unseverability of Land, people, and God is not upheld.[43]

However, it is impossible to substitute or marginalize the Land in a study of the concept of the New Covenant because of the inseparable divine triad of the LORD, the People, and the Land. This union requires that the New Covenant cannot take place only between God and the Nation; the Land must be involved in this relationship and everything it entails since it belongs to the LORD and is the inheritance (Heb. naḥalah) of national Israel. This foundational understanding for the New Covenant in the Old Testament has been noticed by Old Testament scholar Norman Habel:

Any new beginning with YHWH will include YHWH’s personal naḥalah. This beginning will involve a “new planting” in the land and a “new heart” in the people of the land to re-establish the intimacy and purity of the original relationship. Any new order will involve all YHWH’s people, from the least to the greatest, knowing YHWH in a personal way that was once reserved for priests and prophets. And the greatest, under YHWH the shepherd, will know how to execute justice in the land and for the land.”[44]

Therefore, any discussion of the New Covenant, which has its first referent and intended fulfillment with national Israel, must include how the Land of Israel is a part of this fulfillment.

Israel’s New Covenant in the Old Testament

The foremost fact about the New Covenant in the Old Testament is that it was made exclusively with national Israel and will be ultimately fulfilled only by national Israel. This is the essential truth missed by the Reformed school and others who seek to read the Old Testament in light of the New Testament and only see “Christians” in New Covenant passages. As one recovered New Covenant Perspective scholar confessed:

“I had once thought that Jesus came to unveil the New Covenant in what we call the New Testament and that it was entirely ‘Christian’. I had thought that Jewish people could accept their part of the book, but that this New Covenant was the Christian part. As with so much before, I now saw that the New Covenant was made first with the people of Israel, with both the house of Israel and the house of Judah, and it appears first in the Hebrew Scriptures.”[45]

Once it is recognized that the blessings of the New Covenant described in the Old Testament concern national Israel in its Land, all of the details in these blessings become easy to interpret literally and make sense both in the context of Israel’s history and the messianic redemptive plan. It is amusing to read commentaries by scholars, who do not accept this definitive understanding of the New Covenant, ply their imagination and abuse New Testament passages in an effort to conjure a meaning their “New Covenant Perspective” for these texts!

Preparing National Israel in the Land for the New Covenant

The divine intervention that is instrumental in bringing Israel the New Covenant is centered in the LORD’s defense of the Land (Ezek. 38:18-39:6; Zech. 12:4, 8-9; 14:3, 12-15) in a “last days” invasion.[46] The consequent rescue of His People in the Land is part of a series of rescues that take place throughout the Tribulation and ultimately provoke Israel’s national repentance (Ezek. 39:22, 29; Zech. 12:8-13:1) resulting in its experiencing the spiritual blessings of the New Covenant, and secures the Land for the establishment of the Millennial Kingdom (Ezek. 39:7-20, 23-28; Zech. 14:9-11) resulting in the realization of the physical blessings of the New Covenant.

Reunification of National Israel the Land (Ezekiel 37:21-25)

Only under the New Covenant can there peacefully and securely be “one Land for two peoples” and only then when the peoples are “the sons of Israel.” Verse 21 identifies these two sticks with “the sons of Israel” that had been dispersed among the nations and will be regathered into their own Land. Verse 22 speaks of the historic division into “two kingdoms,” while verse 25 speaks of them and their Land in continuity with “Jacob” and “[their] fathers.” Both of these references could apply to none but the historic Jewish people descended from the Patriarchs to whom the Land of Israel was given. Clearly, it is the same Jewish tribes (and only those tribes) that had been divided that would be reunited. Judah was the larger of the two tribes that gave the Southern Kingdom its dynastic ruler (“the house of David)” and its name (1 Kings 12:22-24), just as the Northern Kingdom was called by its most prominent tribe from the house of Joseph, Ephraim (cf. Hosea 5:3, 5, 11-14).

The stages of regathering and reuniting are progressive and sequential with verses 21-22 being the physical regathering to Israel from the nations and verses 23-25 the spiritual regathering and reunification under the Davidic King in the Millennial Kingdom. Prophetically, this pictures Israel’s return to the Land and constitution again as a nation, followed by a national repentance and regeneration at the time of Christ’s second advent. The purpose and result of the national rebirth (cf. Isaiah 66:7-9; Zechariah 12:10-14; Romans 11:26) will be a spiritually cleansed Israel (cf. Zechariah 13:1-2; Romans 11:27) with a new nature incapable of repeating the sins of the past that brought against them the curses of the Mosaic Covenant (verse 23). Under the New Covenant they will finally fulfill their unique calling as people in special relationship to God (verse 24). The singular shepherding of the Davidic King in verses 24-25 has already been discussed in 34:23-24, however, verse 25 adds a familiar feature of the unconditional covenant with its promise of possession of the Land “forever” (Genesis 13:15-18; 2 Chronicles 20:7).

The word “forever” in verse is the first occurrence of a five-fold use of this term in verses 25-26, 28. The repetition of the term is meant to affirm in the strongest way the eternality of God’s renewal and restoration and requires an eschatological projection of the divine program beyond the Millennial Kingdom. The word “forever” translates the Hebrew term ‘olam which denotes “an indefinite period of time;” the duration often defined by the context. For example, in Exodus 21:6 it is used of an Israelite slave who has his ear pierced in token of his pledge to serve his master “forever.” In this case the duration of “forever” is until his service is terminated by his or his master’s death or by the year of Jubilee. However, David Friedman in his doctoral dissertation examined the use of more than 80 biblical uses of ‘olam and concluded that it expresses the time element of “as long as the present heaven and earth exists.”[47] This understanding of the term also takes into account duration for a period of time but reveals that the time is until this present world has run its course. On this basis the Land promise is extended to Israel for “all time” which in context would mean only until the end of the Millennial Kingdom, at which time the present earth will be destroyed and a new earth created (Isaiah 65:17; 66:22; 2 Peter 3:10-13).

The Land as Sanctuary (Ezekiel 37:25-28)

The return of Israel to the Land and to the Lord is now climaxed by the return of the Lord to Israel and the Land (verses 26-28). After this return the New Covenant will be enacted with Israel (Jeremiah 31:31-34) just as the old covenant had been put into effect when the Lord returned to Israel at Mount Sinai (Exodus 19:9-25). The New Covenant is here called both a “covenant of peace” (cf. Isaiah 54:10) and an “everlasting covenant” (cf. Isaiah 55:3; 61:8; Jeremiah 32:40; Ezekiel 16:60-63). As in Ezekiel 34:25-30 where the list of Millennial blessings under the New Covenant is based on the terms of the Mosaic Covenant (Leviticus 26:4-13), here the promise of “peace” for the Land and the “perpetuity” of provision is drawn from Leviticus 26:4, 6. The first synonym “covenant of peace” (verse 26a) is appropriate to describe the restored conditions of the Millennial age since the Hebrew word shalom (“peace”) denotes a comprehensive peace (“security, welfare, health, prosperity, harmony”). The second “everlasting” or “eternal covenant” (verse 26b) describes the nature of God’s enduring promise and the inviolability of His commitment to Israel demonstrated by the historic covenants of the past that have now been fulfilled. The term “everlasting covenant” was used of the Noahic Covenant (Genesis 9:12-16), the Abrahamic Covenant (Genesis 17:7, 13, 19; 1 Chronicles 16:17; Psalm 105:10), and the Davidic Covenant (2 Samuel 23:5; cf. Psalm 89:34-37; Jeremiah 33:21, 26) and the Sabbath and priestly service (Exodus 31:16; Leviticus 24:8; Numbers 18:19; cf. Jeremiah 33:17-26). As proof of the new relationship between God and Israel, verse 26d-28 announces the building of the Millennial Temple and the return of the Divine Presence to Israel. Both Hebrew terms for the “Sanctuary” are used in verses 26d-27a: “and I will set My Sanctuary (Hebrew, miqdash) in their midst forever. My dwelling place (Hebrew, mishkan) also will be over them; and I will be their God, and they will be My people. And the nations will know that I am the Lord who sanctifies Israel, when My Sanctuary (Hebrew, miqdash) is in their midst forever.”

New Testament Texts Affirming the Prophetic Promise of the Land in the New Covenant

When we move from the Old Testament to the New Testament, we remain historically and theologically in the Land of Israel with national Israelites, whether the focus is in the Land or from the Land to other nations. In every case, it is national Israelites taking the Gospel to the Gentiles under the administrative charge of the central apostolic authority in Jerusalem (Acts 15:4). Paul was under this authority (Acts 15:22-29; 21:18-19) and frequently reminded his foreign audience that he was a national Israelite (Acts 26:4), a Pharisee (Acts 26:5), and held to the national promise given by the Prophets, the same promise that was commonly held by all Israel (Acts 26:6-7). Moreover, he asserted he remained loyal to the Temple and the customs of national Israel (Acts 23:1; 24:12, 18; 25:8; cf. Acts 20:16; 21:26), and used the Law of Moses and the Prophets in his preaching to the nations, which he believed was consistent with the message of Jesus (Acts 28:23). Given these historical facts, it is strange to hear Gary Burge declare:

At no point do the earliest Christians view the Holy Land as a locus of divine activity to which the people of the Roman empire must be drawn. They do not promote the Holy Land either for the Jew or for the Christian as a vital aspect of faith. No Diaspora Jew or pagan Roman is converted and then reminded of the importance of the Holy Land. The early Christians possessed no territorial theology. Early Christian preaching is utterly uninterested in a Jewish eschatology devoted to the restoration of the land. The kingdom of Christ began in Judea and is historically anchored there but it is not tethered to a political realization of that kingdom in the Holy Land. Echoing the message of the Gospels, the praxis of the Church betrays its theological commitments: Christians will find in Christ what Judaism had sought in the land.[48]

“This hope is not redefined or clarified in the new era in a way that old promises are lost. It is the hope of the ages for the nation. It is the restoration of order with Israel having a central role. It is, to match the language of Acts 1:6 to which the terminology here alludes, the restoration of the kingdom to Israel. What Gabriel promised to Mary, what Mary hoped for, and what Zacharias predicted of Jesus in Luke 1-2 is what Peter hoped for here. There is a kingdom hope that applies to Israel and that is explained in what is now called the OT. The existence of the church has not canceled that hope for Israel.”[49]

The Land in the New Testament

We should not be surprised that there is no concerned mention for the Land in the New Testament because the time its events record, as well as the time of its writing, national Israel was still in the Land. It is true though that independent rule had been lost with the Roman invasion under Pompey (63 B.C.), and this concern is stated in the disciples’ question to the Lord concerning “restoring the kingdom to Israel” (Acts 1:6). However, restoration to the Land was not at issue since Jesus entire ministry was Land-based and the first church was centered in Jerusalem (Acts 1:12, 15; 2:14, 46; 3:1, 11; 4:27; 5:12, 16, 22, 28, 42; 6:7; 7:58; 8:1; 13:13; 15:4). The Lord’s commission in Acts 1:8 was certainly to take His witness to “the remotest parts of the earth,” but it was to begin in the capital city of “Jerusalem” and continue to the whole Land of Israel (“Judea and Samaria”). Even the Book of Revelation, though written to diaspora communities after the Roman destruction of the Temple, appears to have its prophetic events centered in the Land.[50] Before the Temple’s destruction, the diaspora communities felt connected to the Land via their contributions to the Temple, and it is only after the Hadrianic ban on Jews Jerusalem after the second Jewish revolt that exile (galut) from the Land becomes a voiced concern. This, of course, was well after the orthodox New Testament canon had been completed. Taking this into account, we should not expect the epistolary concern to be Israel’s restoration, but the church’s relationship. Moreover, the Bible of the early church already offered a complete manual on the subject of the Land and its future restoration. S. Lewis Johnson, Jr. makes this point when he writes:

What about the land promises? They are not mentioned in the NT. Are they, therefore, canceled?” In my opinion the apostles and the early church would have regarded the question as singularly strange, if not perverse. To them the Scriptures consisted of our OT, and they considered the Scriptures to be living and valid as they wrote and transmitted the NT literature. The apostles used the Scriptures as if they were living, vital oracles of the living God, applicable to them in their time. And these same Scriptures were filled with promises regarding the land and an earthly kingdom. On what basis should the Abrahamic promises be divided into those to be fulfilled and those to remain unfulfilled? Finally, there is no need to repeat what is copiously spread over the pages of the Scriptures. There seems to be lurking behind the demand a false principle, namely, that we should not give heed to the OT unless its content is repeated in the New.[51]