A Case for the Futurist Interpretation of the Book of Revelation

Dr. Andy Woods

Introduction

While previous generations of dispensational interpreters may have enjoyed the luxury of the widespread assumption that the Book of Revelation primarily concerns future events, such a "golden age" has now come to an end. Today, many scholarly and popular commentators alike are aggressively challenging the futurist interpretation of Revelation. Perhaps the most vociferous challengers to the futurist position come from the works of partial preterists who contend that the futuristic section of the book (4-22) was mostly fulfilled in the events surrounding the fall of Jerusalem in A.D. 70.[1] They believe that the Book of Revelation was penned in the mid 60’s and predicts God’s divorce and A.D. 70 judgment upon harlotrous, national Israel due to her rejection of Christ. At that time, God was also at work creating the new universal, international church to permanently replace disgraced and judged Israel (John 4:21; Gal 3:9, 28-29; 6:16; Eph 2:14). However, partial preterists are quick to distinguish themselves from full preterists by still holding to a future bodily return of Christ and final judgment (20:7-15).[2]

The partial preterist relies upon several key texts in Revelation in order to portray the book as a prediction that was essentially fulfilled two thousand years ago. However, as this paper will show, these texts actually end up arguing for futurism rather than preterism. Although time constraints prevent an exhaustive study on how preterists handle the entirety of the book, this paper will highlight several textual arguments relied upon by partial preterist Kenneth Gentry in some of his recent material surveying the Book of Revelation.[3] While some futurists may believe that the preterist early date scheme ends the debate, this paper will attempt to show that the preterist system should be rejected regardless of whether one holds a Neronic (A.D. 65) or Domitianic date (A.D. 95) for the composition of the book since the text itself favors futurism over preterism.

Hermeneutics

As with most theological controversies, differences among competing viewpoints are rooted in different hermeneutical methodologies.[4] This principle holds true in the dispute between preterists and futurists. The futurist applies a consistently literal or normal[5] interpretive grid. This method attaches to every word the same meaning that it would have in normal usage, whether employed in speaking, writing, or thinking.[6] It also entails interpreting the Apocalypse according to the same hermeneutical rules that one employs when interpreting any other section of Scripture.[7]

Although its theological opponents often malign the normal hermeneutical method as a wooden and inflexible literalism that fails to consider Revelation’s symbolic character and multiple figures of speech,[8] such a characterization is erroneous. As in ordinary communication, the normal interpretive method recognizes symbolism and figures of speech when they are conspicuous in the text. Clues such as the adverb "spiritually" (11:8), the noun "sign" (12:1), the comparative words "like" or "as" (8:8), direct correspondence with Old Testament concepts (Rev 13:2; Dan 7), and interpretations of visions found within the same context (17:18) all alert the interpreter to the reality that symbolism and figures of speech are being employed. When the interpreter encounters such language he is assisted by either the immediate context (12:3, 9), the Old Testament (12:1; Gen 37:9-10), and the notion of comparison inherent in a simile (8:8) in order to discern the meaning of the figure of speech or symbol being used.

A consistent application of a literal approach to Revelation logically leads the interpreter away from viewing the book’s contents as being fulfilled in the past and instead leads to the futurist interpretation.[9] A relationship exists between literalism and futurism because the ordinary import of Revelation’s words and phrases make it impossible to argue that Revelation’s contents have already been fulfilled. The destruction of half of the world’s population (Rev 6:8; 9:15) and the greatest earthquake in human history (Rev 16:18) obviously have never taken place. In fact, we might ask how else God could have possibly communicated global, futuristic concepts if this language is not allowed to do so?

However, the preterist escapes the normal meaning of language by assuming that Revelation is part of the "apocalyptic genre." This classification presupposes that Revelation belongs to a special group of non-canonical writings that flourished from the intertestamental period into the first century[10] "where symbolism is the rule and literalism is the exception." [11] This categorization functions as a sort of "get out of jail for free card." Whenever the details of Revelation’s text do not square with the A.D. 70 events, the apocalyptic assumption allows the preterist to theorize that John is merely employing elevated apocalyptic hyperbole. Such a device allows the preterist to "cram" Revelation’s contents back into the first century regardless of the text’s global language.[12]

By way of analogy, during my law school days my professors used to say that the United States Constitution is a "living and breathing document." Such a genre categorization is popular among legal academics because it allows them to dispense with authorial intention and simultaneously gives them the literary license to read their own ideology into the text. Classifying Revelation as apocalyptic literature similarly allows the preterist to reach his theological conclusion of an A.D. 70 realization regardless of inconvenient textual details. However, the assumption that Revelation is part of the apocalyptic category can be countered by noting that any similarities it has with these non-canonical works are outweighed by notable differences between the two.[13]

Table 1[14]

|

Apocalyptic Genre |

Revelation |

|

Pseudonymous |

Not pseudonymous |

|

Pessimistic about the present |

Not pessimistic about the present |

|

No epistolary framework |

Epistolary framework |

|

Limited admonitions for moral compliance |

Repeated admonitions for moral compliance |

|

Messiah’s coming exclusively future |

Basis for Messiah’s future coming is His past coming (Rev 5:9) |

|

Does not call itself a prophecy |

Calls itself a prophecy |

|

Traces history under the guise of prophecy (vaticina ex eventu) |

Futuristic prediction |

|

Primarily concerns a future generation (1 Enoch 1:2) |

Concerns both the generation of the author (2-3) and a future generation (4-22) |

Revelation’s "Time Texts"

The argument most relied upon by preterists to contend for a first century fulfillment is Revelation’s so called "time texts." Because Revelation makes use of the words "shortly" or "quickly" or τάχος (Rev 1:1; 2:16; 3:11; 11:14; 22:6, 7, 12, 20), "near" or "at hand" or ἐγγύς (Rev 1:3; 22:10), and "about to" or μέλλω (1:19; 3:10), preterists believe that they have the literary license to locate the fulfillment of most of John’s prophecies in A.D. 70.[15] However, the preterist errs in assuming that these words are technical expressions that always have the same definition every time they are used. In fact, each of these terms has a broad semantic range and therefore its meaning must be determined by its context rather than through the imposition of an artificial "one size fits all" grid.

For example, besides always understanding these words chronologically indicating when Christ will return, it is also possible to understand them adverbially or qualitatively indicating the manner of Christ’s return. In other words, when the action comes it will come suddenly or with great rapidity.[16] The New Testament allows for such a usage. For example, while it is true that Scripture often uses "shortly" or "quickly" (τάχος) in a chronological sense to indicate "when" (1 Timothy 3:14), Scripture also uses the same word in a qualitative sense to indicate "how." For instance, Acts 22:18 uses tacos to indicate manner when it says, "Make haste, and get out of Jerusalem quickly, because they will not accept your testimony about me." The LXX also displays an adverbial use of these expressions by using them in prophetic contexts that would not be fulfilled for hundreds and sometimes thousands of years or more into the future (Isa 13:22; 51:5; Zeph 1:7, 14; Obad 15; cf. Isa 5:26; 13:6; 58:8; Joel 1:15; 2:1; 3:14).[17] Given the broad semantic range of these terms, "context is king" in determining whether the chronological or adverbial meaning is applicable. Because the context of Revelation involves global events that have not yet come to pass, an adverbial rather than a chronological meaning should be assigned to these words.[18]

While Revelation’s "timing texts" pose no obstacle to the futurist interpretation, these texts pose considerable problems for the preterist interpreter. Partial preterist interpretive problems are created by the fact that Revelation's "timing texts" are found at the end of the Book of Revelation as well as the beginning (Rev 22:6, 7, 10, 12, 20). The partial preterist system still wants to hold to a future bodily appearing and final judgment (Rev 20:7-15). However, the use of τάχος and ἐγγύς in Revelation 22 is injurious to the partial preterist system, because the existence of these words at the end of the book logically leads to the conclusion that the entire Book of Revelation was fulfilled in A.D. 70 rather than just most of it. If the use of τάχος and ἐγγύς in the early chapters of Revelation lead partial preterists to conclude that most of the book’s prophecies were fulfilled in A.D. 70, then surely these identical words found at the end of the book should also lead to the conclusion that the entire book was fulfilled in A.D. 70.

In essence, it is impossible to be a consistent partial preterist because the logical corollary of partial preterism is full preterism. In actuality, the designations "partial preterist" and "full preterist" are misnomers. Rather, partial preterists should be labeled "inconsistent preterists" while full preterists should be referred to as "consistent preterists." This inconsistency is evident even to some partial preterists, such as David Chilton, who abandoned his partial preterist system in favor of full preterism.

Because of the use of τάχος and ἐγγύς in Revelation 22, in order for partial preterists to be consistent, they also must believe that the Second Advent and final judgment have already taken place. Such a belief is at odds with the great ecumenical church creeds, which teach a future bodily appearing of Christ. Denying the Second Advent takes one outside the pale of orthodoxy and into the camp of heterodoxy or heresy. Thus, the partial preterist understanding of Revelation’s timing texts flirts dangerously with unorthodoxy.[19]

Theme of the Book of Revelation (Rev 1:7)

Rather than seeing Revelation 1:7 as speaking of Christ’s Second Advent, preterists believe this verse signals Revelation’s theme as God’s A.D. 70 judgment upon apostate Israel. The verse supposedly teaches that Christ came non-bodily through the Roman armies to judge Israel for her rejection of Him. Preterists attempt to make their case by appealing to Scripture’s frequent use of cloud imagery to depict non-bodily, divine judgment (Isa 19:1), the Jewish guilt borne by the Jews for crucifying Christ (Acts 2:22-23), associating "tribes" with Jews, and interpreting "earth" (gh') as the land of Israel.[20] However, there are at least two problems with this interpretation.[21]

First, the phrase "all the tribes of the earth" (pas phylē γη) always has a universal rather than local nuance whenever it is employed in the Old Testament (Gen. 12:3; 28:14; Ps 72:17; Zech 14:17). This phrase refers to all the nations in every one of its Septuagint occurrences and never refers to the Israelite tribes.[22] Second, the term "earth" (γῆ) most likely has a universal meaning rather than a local meaning in the context of Revelation 1:7. Although the term "earth" (γῆ) can have a local meaning by referring to the nation of Israel (1 Sam 13:19; Zech 12:12; Matt 2:6), it can also have a universal meaning by referring to all the earth (Gen 1:1; Matt 5:18). In fact the universal use of the word "earth" is found just a few verses earlier (1:5) as well as at the end of the book (21:1).

Thus, the meaning of the term depends upon the context in which it is used. Because of the global context of 1:7 ("every eye" and "all the tribes of the earth") as well as the rest of the book, the universal rather than local meaning of "earth" fits best. By interpreting the phrase "earth" (γῆ) in Revelation 1:7 to mean exactly the same thing that it means in a few other isolated contexts (1 Sam 13:19; Zech 12:12; Matt 2:6), preterists are guilty of committing a hermeneutical error known as "illegitimate totality transfer." This error arises when the meaning of a word as derived from its use elsewhere is then automatically read into the same word in a foreign context.[23]

Relevance to the Seven Churches of Asia Minor (Rev 2-3)

Preterists contend that interpreting Revelation’s prophecies as concerning the distant future is to make the book irrelevant to the seven churches, which were John’s original addressees. Preterists contend that interpreting Revelation in such a manner is to engage in a cruel "mockery" of the adverse circumstances of the seven churches.[24] Such a contention is without merit. It is quite common throughout the Old Testament prophetic material for God to comfort His people in the present by furnishing them with a vision of the distant future. The Book of Isaiah amply refutes the idea that the prophecy must relate to the writer’s original audience. Isaiah not only sought to address the needs of his own day (Isa 1-35) but also the needs of a future generation of Jews in Babylonian Captivity (Isa 40-55). Also, Isaiah’s futuristic prophecies as recorded in Isaiah 40-66 were designed to comfort Israel in her present adverse circumstances in 700 B.C.

This same pattern is seen in other Old Testament prophetic material (Ezek 34-48; Amos 9:11-15; Zech 12-14). Revelation simply follows this Old Testament pattern by providing the persecuted churches (Rev 2-3) with a futuristic vision communicating that God will ultimately conquer all forces oppressing the church at the end of history (Rev 4-22). In fact, even the partial preterist system recognizes this practice. While partial preterists hold to a future return and judgment in Revelation 20:7-15,[25] many of the exhortations that Christ gave to the seven churches are drawn from that section of Scripture (3:5 and 20:15; 2:11 and 20:14).

In actuality, it is the preterist interpretation that makes Revelation irrelevant to the seven churches. For example, although the preterist understands the persecution of the beast in Revelation 13 as the Neronian persecution, that persecution was confined to the city of Rome and consequently never reached Asia Minor.[26] Regarding the destruction of Jerusalem, "What does a localized judgment hundreds of miles away have to do with the seven churches of Asia?...the promise to shield the Philadelphia church from judgment is meaningless if that judgment occurs far beyond the borders of that city." [27]

Preterists attempt to overcome this relevance problem by appealing to local enemies taking advantage of the general anti-Christian sentiment ushered in by the emperor’s Roman persecution[28] as well as the "aftershocks" of Jerusalem’s destruction.[29] However, these solutions are unsatisfying since they fail to tightly connect the predicament of the churches with either the Neronian persecution or the A.D. 70 events. Also without merit is the notion that the destruction of Jerusalem was relevant to the churches by ridding them of their tendency to gravitate back toward Jewish customs.[30] The permanent rift between Judaism and Christianity did not begin until the 90’s and did not reach its final form until the events surrounding the Bar Cochba revolt in A.D. 135.[31]

God’s Divorce Decree (Rev 5)

Most dispensationalists understand the seven-sealed scroll as the title deed to the earth that will bring about first of all judgment and then the kingdom including Israel’s ultimate restoration. However, the preterist understands this scroll as "God’s divorce decree against his Old Testament wife for her spiritual adultery" and ultimate sin of rejecting Christ.[32] Gentry attempts to bolster his case by appealing to various Old Testament concepts. For example, he sees a connection between the seven-fold nature of the seal judgments and the seven-fold nature of Israel’s covenant curses (Lev 26:18, 24, 28). However, the rest of the chapter does not predict God’s permanent casting aside of Israel but rather her eventual restoration (Lev 26:40-46). Therefore, these covenant curses represent mere temporal discipline rather than a wholesale rejection.

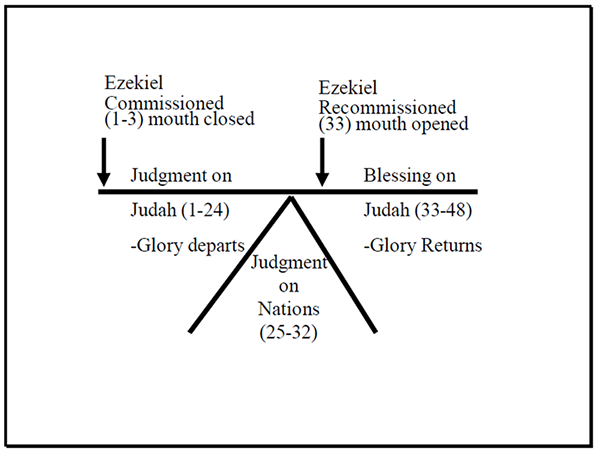

Moreover, Gentry parallels the scroll in Revelation 5 with the scroll of Ezekiel 2:8-3:3, which represents a message of judgment against Judah that was fulfilled in the Babylonian Captivity.[33] However, when the Book of Ezekiel is taken as a whole it does not teach a permanent divorce of Israel but rather a mere temporal discipline of God’s chosen people. As depicted on the following chart, the Book of Ezekiel contains three major sections.[34]

While the first two sections represent God’s judgment upon Judah and the surrounding nations, the final section represents God’s intention of ultimately restoring His elect nation physically and spiritually. Thus, the scroll of Ezekiel 2:8–3:3 represents only the discipline of the Babylonian Captivity rather than a permanent severance between God and Israel.

National discipline rather than divorce is also the theme of the Book of Revelation, which concludes with a portrayal of Israel’s restored state (Rev 20:9). There is little doubt that this "beloved city" that is featured prominently in the millennium is Jerusalem. The Old Testament often describes Jerusalem in the same manner (Ps 78:68; 87:2; Jer 12:7) and also predicts her future return to glory (Isa 2:2-4; Zech 14:17). Thomas explains Israel’s preeminence in the millennial age: "At the end of the Millennium that city will be Satan’s prime objective with his rebel army, because Israel will be leader again among the nations." [35] Thus, far from being a book about the divorce of Israel, Revelation is actually about Israel’s eventual restoration. The reason for the parallels between the scroll of Ezekiel 2:8-3:3 and the scroll of Revelation 5 is that the theme of temporal discipline leading to restoration is the theme of both books.

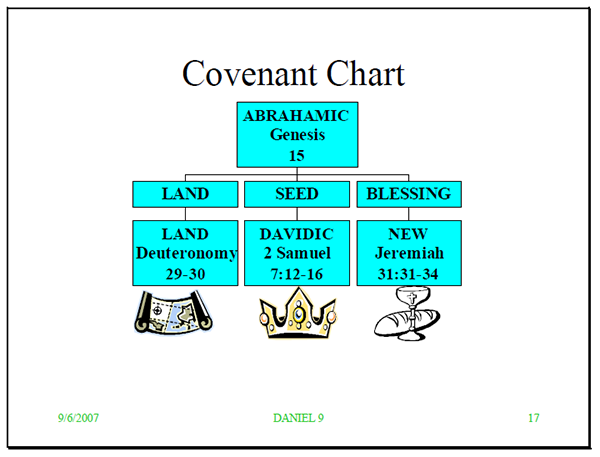

To contend that God divorced Israel in the events of A.D. 70 is to misunderstand the Abrahamic Covenant (Gen 15), which is the foundation of God’s subsequent covenants with Israel.

Not only is the covenant language unconditional but it also remains unfulfilled. The covenant’s unconditionality is evidenced by the fact that God alone passed through the animal pieces in the solemn ANE covenant ratification ceremony while Abraham remained asleep. Other evidence of unconditionality includes the lack of any stated conditions for Israel’s obedience in Genesis 15, the covenant’s subsequent designation as both eternal (Gen 17:7, 13, 19; 1 Chron 16:17; Ps 105:10) and immutable (Heb 6:13-18), and the covenant’s trans-generational reaffirmation to Israel throughout her national existence despite her perpetual disobedience.[36] This unconditional feature of Israel’s covenant structure explains why after the giving of the New Covenant, God stated that as long as the fixed order of the sun, moon, and stars remained, Israel would also continuously exist (Jer 31:35-37).

Preterists typically challenge the covenant’s unfulfilled aspects by contending that it was fulfilled either in the days of Joshua (Josh 11:23; 21:43-45) or during the prosperous portion of Solomon’s reign (1 Kings 4:20-21; 8:56).[37] However, several reasons make this interpretation suspect. First, the extended context indicates that the land promises were not completely satisfied in the days of Joshua (13:1-7; Judg 1). Second, the land that Israel attained in the conquest was only a fraction of what was found in the Abrahamic Covenant.[38] Third, the land promises could not have been fulfilled in Joshua’s day since Israel had not yet conquered Jerusalem (15:63). The conquest of Jerusalem would have to wait another four hundred years until the Davidic reign (2 Sam 5). Fourth, the Abrahamic Covenant promises that Israel would possess the land forever (Gen 17:8). This eternal promise has obviously never been fulfilled due to Israel’s subsequent eviction from the land after Solomon’s reign. Fifth, if the land promises were satisfied in Joshua’s or Solomon’s day, then why do subsequent prophets treat these promises as if they are yet to be fulfilled (Amos 9:11-15)?[39]

Because of the nation’s unconditional and unfulfilled covenant structure, a divine divorce of Israel is impossible. If God can cast aside His covenant promises to His elect nation, then His character is fickle and all of the promises He has made to His church are similarly untrustworthy. Thus, Paul expounds upon God’s covenant faithfulness to Israel (Rom 9-11) immediately after detailing the unconditional promises that He has made to the church age believer (Rom 8:18-39). In other words, because God cannot divorce Israel, we know that He will never divorce the church.

The 144,000 (Rev 7)

Most dispensationalists understand Revelation 7 as speaking of 144,000 Jews (Rev 7:1-8) who will evangelize the world in the future tribulation period (Rev 7:9-17). However, the preterist understands Revelation 7 as conveying a pause in the action involving Jerusalem’s A.D. 70 destruction when God begins to form "new Israel" or the church to permanently replace harlotrous Old Testament Israel.[40] However, the preterist must rely on several tenuous propositions in order to reach this conclusion. First, he must deliteralize the numbers 12,000 and 144,000. However, one wonders how God could have possibly communicated the idea of 144,000 Jews emanating from each of Israel’s twelve tribes if the language of Revelation 7:1-8 is insufficient for the task? Moreover, these numbers must be taken as specific numbers rather than as mere generalities since John was quite adept at expressing generalizations when it was his desire to do so. Even within this same chapter, John uses the phrase "a great multitude which no one could count" (Rev 7:9) to express a general figure. Yet in Revelation 7:4-8, John does not use a similar generality but rather provides specific numbers.

Second, the preterist understands those mentioned in Revelation 7:4-8 to also include non-Jews. While Gentry understands those in Revelation 7:4-8 as "Jewish converts in Israel" that "are the beginning of the new covenant phase of the church," [41] Hanegraaff sees the 144,000 as just another description of the innumerable multitude that appear later on in the same chapter.[42] However, this is a strange interpretation coming from someone who claims that "the background music of the Old Testament" informs his reading of Revelation.[43] The Old Testament itself presents the tribes as literal, historic entities (Gen 29-30). Furthermore, the 144,000 (7:1-8) and the innumerable multitude (7:9-17) should not be intermingled or confused as the chapter plainly presents them as two separate groups.[44]

| Revelation 7:1-8 |

Revelation 7:9-17 |

|

Numbered (144,000) |

Innumerable |

|

Jews |

All nations |

|

Sealed |

Slain |

|

Sealed before tribulation |

Converted out of tribulation |

Third, the preterist understands the 144,000 as the church. However, this assertion is made in spite of the fact that the word church or ekklēsia is not found within the chapter and is also virtually absent in Revelation’s third major section (4-22). While the word church is found 19 times in the book’s first three chapters (1-3), the word disappears almost entirely in chapters 4-22 and does not reappear until Revelation 22:16 when John concludes the book. Fourth, the preterist must understand the 144,000 and the innumerable multitude as the new or "true Israel." [45] This contention is made in spite of the fact that the New Testament uses the word Israel 73 times and never once is this word used as a synonym for the Gentiles or the church.[46]

Fifth, the preterist must ignore the global language of Revelation 7:9. Here, John uses four terms (nations, tribes, peoples, and tongues) to describe the innumerable multitude. Interestingly, John uses these identical words earlier to refer to those for whom Christ died (5:9). If these four terms connote universalism in 5:9, then surely these same four terms must also convey universality rather than locality just a few chapters later. Sixth, the preterist dismisses the futurist interpretation of Revelation 7 on the grounds that the tribes of Israel were lost after 722 B.C. and A.D. 70 and therefore could not be regathered as mandated by a futuristic interpretation of the chapter.[47] However, while these tribes may be lost to man they are not lost to God. To doubt an omnipotent God’s ability to preserve and regather Israel’s tribes is reminiscent of the Sadducees in Christ’s day that doubted God’s future ability to resurrect the dead (Matt 22:23, 29). Interestingly, a number of New Testament passages written long after 722 B.C. indicate that the tribes were not lost (Jas 1:1b; Acts 26:7).

The Temple (Rev 11)

Rather than seeing the temple of Revelation 11 as the third rebuilt Jewish temple that the antichrist will desecrate mid-way through the future tribulation period, the preterist interprets it as the second Herodian temple that was allegedly standing in John’s day.[48] However, this analysis suffers from at least four inadequacies.[49] First, it is entirely possible for a biblical writer to refer to a temple that is yet future from the perspective of the writer. Biblical writers at times describe future events that are divinely relayed to them in a vision.

For example, both Daniel and Ezekiel make reference to a temple (Daniel 8:11-14; 9:27; 11:31: 12:11; Ezekiel 40-48). Chronological information revealed in these books leads to the conclusion that these exilic prophets experienced their temple visions during a time when there was no physical temple standing in Jerusalem. For example, Daniel’s temple visions occurred in 551, 538, and 536 B.C. (Dan 8:1; 9:1; 10:1). Similarly, Ezekiel’s temple vision transpired in 573 B.C. (Ezek 40:1). Since the Jerusalem temple was destroyed in 586 B.C. (Ezek 33:21) and was not rebuilt until 515 B.C. (Ezra 6:15) both Ezekiel and Daniel are describing a future temple rather than an existing one. Why cannot John be doing the same thing in Revelation 11? The fact that Revelation constitutes such a futurist vision rather than merely a recounting of contemporary historical circumstances is evident from the repetitive use of the verbs "I saw" (ὁράω) and "I heard" (ἀκούω) found throughout the book.[50]

Second, how could John be expected to recount detailed information about the temple that was allegedly standing in Jerusalem when he was confined hundreds of miles away on Patmos at the time of writing? To argue that John recorded the information in Revelation 11 based upon memory (John 14:26) or a vision does not help the preterist cause since these sources of information do not require the contemporary existence of the Jerusalem temple. Third, even if it is assumed that Revelation 11:1-2 refers to Herod’s temple that was destroyed in A.D. 70, how is it possible to fit the rest of the contents of Revelation 11 into the events of A.D. 70? For example, much of the rest of Revelation 11 is devoted to a discussion of the two witnesses who perform miracles, are slain, are gazed upon by the world, lie dead for three and a half days, resurrect, and ascend to heaven. These events are not even hinted at in Josephus' detailed accounts that discuss the siege of Jerusalem.[51] Gentry explains that the two witnesses "probably represent a small body of Christians who remained in Jerusalem to testify against" the temple. "They are portrayed as two, in that they are legal witnesses to the covenant curses." [52] However, why should a literal hermeneutic be used to understand the temple and the 42 months in the early part of the chapter (Rev 11:1-2) while a spiritualizing hermeneutic is applied to interpret the two witnesses in the very next unit of the same chapter (Rev 11:3-14)?

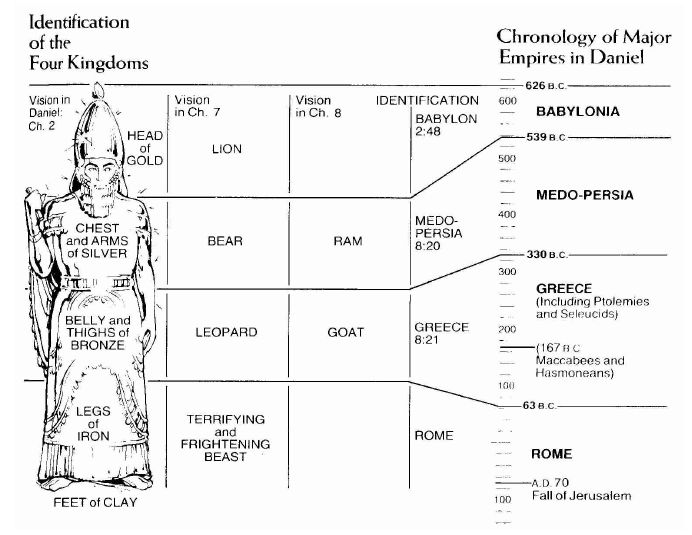

Fourth, Gentry contends that the trampling down of the temple by the Gentiles for 42 months (11:2) refers to the conclusion of the "Times of the Gentiles" from A.D. 67-70. According to this scenario, the "Times of the Gentiles" ended in A.D. 70. The temple’s destruction prevented the Gentiles from trampling any longer upon the material worship of God because now such worship was to be sourced in God’s international, universal kingdom/church (John 4:21).[53] However, this view requires an inconsistent hermeneutic in interpreting the statue portraying the "Times of the Gentiles" in Dan 2.[54]

While acknowledging that the four Gentile empires given in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream (Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, and Rome) were literal, geopolitical empires,[55] Gentry’s interpretation requires that the smiting stone recorded at the conclusion of the dream be given a spiritualized interpretation. In other words, most of the statue must be read with one hermeneutical lens while the statue’s feet, destruction, and replacement must be read with another hermeneutical lens. Furthermore, Pentecost notes inconsistencies associated with locating the fulfillment of the smiting stone aspect of the dream in the first century. At that time, "Christianity did not suddenly 'fill the whole earth' (Dan 2:35)," Rome was not destroyed, the Roman Empire did not consist of ten simultaneous kings, Christ was not a smiting stone, Christ did not put an end to all the kingdoms of the world, and Christ did not usher in a political kingdom.[56]

The Woman in the Wilderness (Rev 12)

While the dispensationalist understands the woman in Revelation 12 as Israel fleeing from Satan during the second half of Daniel’s 70th week, Gentry believes that this chapter represents the persecution of the mother Jerusalem church (the woman) by Satan. Gentry notes, "In Revelation 12 John backs up chronologically in order to show the 'mother' church in Jerusalem, which was being protected from Satan inspired resistance. This would cover the time frame from Christ’s ministry through the Book of Acts up until the destruction of Jerusalem." [57] However, equating the woman with the church is problematic because the word "church" or ekklēsia appears nowhere in the chapter, and, as previously stated, is virtually absent from the book’s third section (4-22). Equating the woman with the church also raises a chronological problem since Revelation 12:5 portrays the woman giving birth to Christ. However, it was Christ who gave birth to the church (Matt 16:18) not the church who gave birth to Christ. Thomas explains, "It would be impossible to regard the Jewish Messiah of 12:5 as a child of the Christian community, as he clearly is of the Jewish community." [58]

On account of the similarities between John’s description of the woman (Rev 12:1) and Joseph’s dream (Gen 37:9-10), viewing the woman as national Israel is better than viewing her as the Jerusalem church. John associates the woman with the sun, moon, and twelve stars (Rev 12:1) and Joseph’s dream interprets these respective luminaries as the patriarch (Jacob), matriarch (Rachel or Leah), and twelve tribes of Israel (Gen 37:9-10).[59] Interpreting the woman as Israel rather than the church is strengthened by the Jewish context of the immediately preceding chapter, which mentions the Jewish temple (11:1-2), witnesses (11:3-13), and Ark (11:19).[60] Furthermore, it is difficult to locate the events of this chapter in pre A.D. 70 history. Chilton believes "...the Woman’s flight into the wilderness is a picture of the flight of the Judean Christians from the destruction of Jerusalem..." [61] However, when did the miraculous preservation occur as recorded in Revelation 12:14-16? Also, the eagle’s wings imagery (12:14) is reminiscent of the Exodus event (Exod 19:4) where millions of Jews were preserved. Yet no miraculous preservation of similar magnitude transpired prior to A.D. 70.[62]

The Beast = Nero (Rev 13)

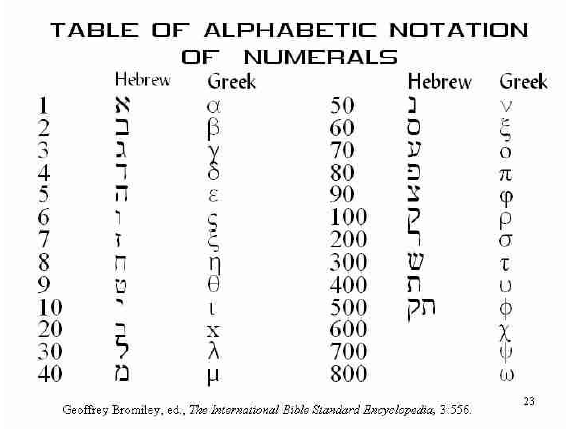

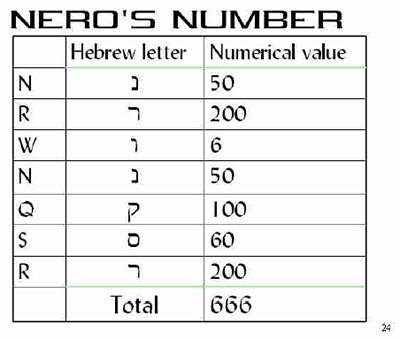

Rather than seeing the first beast as the antichrist, preterists interpret him as Nero.[63] The main selling point of this view is gematria, which is the reality that alphabets of the ancient world not only served a phonetic purpose but also served as numerals.

Thus, a person’s name could be converted into a number simply by adding up all of the mathematical values of the letters of their name. Transliterating the Greek title "Caesar Nero" into Hebrew yields the name rsq nwrn. The numerical sum of these letters yields the total 666 (Rev 13:18).

However, the Nero calculation is fraught with problems.[64] First, why do preterists treat Revelation’s other numbers (1,000; 12,000; 144,000; etc...) symbolically while simultaneously approaching 666 with such iron clad literalism that it supposedly yields a person’s name? Gentry’s explanation that Revelation’s large rounded numbers are symbolic while the shorter unrounded numbers are literal[65] is unsatisfying and leaves readers with the impression that he is inconsistently vacillating between hermeneutical methods in support of a predetermined theological outcome. Second, the transliteration from Greek into Hebrew is problematic given the fact that the Book of Revelation was written to a Greek speaking audience (Rev 2-3). Gentry attempts to counter this assertion by pointing out Revelation’s Hebraic character.[66] However, when John uses Hebrew words in Revelation, he makes a special note of it in order to bring it to his readers' attention (Rev 9:11; 16:16). Yet no similar special designation is even hinted at in Revelation 13:18 regarding the number 666.[67] Third, the Neronic calculation was never suggested as a solution by any of the ancient commentators[68] including Irenaeus, who was discipled by Polycarp who in turn was discipled by John.[69] Fourth, it appears that preterists have "cherry picked" a peculiar Neronic spelling in an attempt to reach an ordained result given the fact that Nero had many other names and titles[70] and that rsq can also be spelled with an additional yod (rsyq).[71]

Besides these problems, the rest of the events of Revelation 13 do not fit the known facts of history. For example, while arguing that the Neronic persecution lasted 42 months, Gentry tacitly admits that the persecution was not an exact 42 months through his use of the expression "but for a few days." [72] Such ambiguity contradicts prophecy’s track record of past literal fulfillment (Dan 9:24-26; Luke 19:42).[73] Also, Nero did not force the entire world to take a mark on their right hand or forehead in order to participate in the global economy (13:16-18), coerce the entire world to worship a singular image of him (13:15), resurrect from the dead (13:14), associate with the miracle working false prophet (13:13, 15), and receive veneration from the entire planet (13:8).[74]

The global nature of this chapter is undeniable. As is the case in 7:9, the same four terms that are used earlier by John to describe Christ’s universal atonement (Rev 5:9) are also used in 13:7 to depict the scope of the beast’s worldwide rule.[75] Even partial preterists recognize the global nature of the terms used in this chapter. Unfortunately, while recognizing the global nuance of the merism "great and small" in 20:11, they fail to appreciate the global significance of the nearly identical expression in 13:16. In sum, the Nero view is built upon a few commonalities between his reign and chapter 13 while ignoring the vast differences between the two. While futurists are sometimes guilty of forcing unwarranted biblical connections on the basis of recent headlines, preterists are no less guilty of such "newspaper exegesis" when they force the text of Revelation 13 to fit a predetermined scenario based upon the first century newspapers of Josephus and others.

The Babylonian Harlot = Jerusalem (Rev 17-18)

Rather than interpreting Babylon of Revelation 17-18 as something that will exist in the future, the preterist understands Babylon as the city of Jerusalem that was destroyed in A.D. 70. The Babylon = Jerusalem view forms the "epicenter" of the preterist interpretation since it represents the punishment of God’s harlotrous Old Testament wife Israel for her rejection of Christ thus liberating God to raise up his new bride or the universal, international church, in her place (Rev 20-22). The main rationale for the view is that earlier John describes Jerusalem as "the great city" (11:8). Since Babylon is also depicted as "the great city" (18:10) Babylon must be Jerusalem.[76]

However, this procedure represents a hermeneutical error known as "illegitimate totality transfer." This error arises when the meaning of a word or phrase as derived from its use elsewhere is then automatically read into the same word or phrase in a foreign context.[77] Jerusalem advocates commit such an error when they define "the great city" in Revelation 17-18 from how the same phrase is used in totally different contexts elsewhere in Revelation. Such a hermeneutical approach neglects the possibility that Revelation could be highlighting two "great cities," both Jerusalem and Babylon. The phrase "great city" does not uniquely identify Jerusalem since both Babylon (Dan 4:30) and Rome[78] were given the same designation. Another rationale behind the Babylon = Jerusalem view is that because national Israel is routinely portrayed as a harlot throughout the pages of the Old Testament (Jer 2-3; Ezek 16; 23; Hos 9:1), the harlot of Revelation 17-18 must also be Israel or Jerusalem.[79] However, the mere existence of harlot imagery does not uniquely identify Jerusalem since the Old Testament also uses harlot imagery in connection with the Gentile cities of Tyre (Isa 23:16-17) and Nineveh (Nah 3:4).[80]

The Jerusalem view suffers from at least three weaknesses. First, there is no reason why the word "Babylon" as used in chapters 17-18 cannot retain its ordinary meaning. Although not all names in Revelation are meant to be understood literally (Rev 2:20), it does seem to be a general rule that the names of cities and geographical regions are literal. For example, most interpreters typically understand the following places and cities in Revelation literally: Asia (1:4), Patmos (1:9), Ephesus (2:1), Smyrna (2:8), Pergamum (2:12), Thyatira (2:18), Sardis (3:1), Philadelphia (3:7), Laodicea (3:14), the Euphrates (Rev 9:14; 16:12) and Armageddon (16:16).[81] Why should the city of Babylon, depicted in Revelation 17-18, not be given the same literal interpretation?

Moreover, when John wants to communicate that he is using a city in a non-literal sense, he makes this explicit as in 11:8 where he says "the great city which is spiritually called Sodom and Egypt." [82] Because no similar formula is found in Revelation 17-18 to alert the reader to the reality that John is speaking of the city of Babylon figuratively, there is no reason that Babylon should be interpreted non-literally.[83] Interestingly, all the way through Scripture Babylon always means Babylon and Jerusalem always means Jerusalem. These two cities are even distinguished from one another as late as Revelation 16:19.[84] However, when interpreting Revelation 17-18, the preterist inverts the consistent and natural meaning of these words as "Babylon" abruptly takes on the new meaning "Jerusalem."

The preterist seeks to get around this problem by positing that Babylon is merely a code word for Jerusalem. However, to refer Jerusalem to Babylon is "unprecedented." [85] While Scripture typically relates Jerusalem to the people of God, it relates Babylon to the world.[86] Although Sodom and Egypt have precedent for being used as a metaphor for Jerusalem (11:8), Babylon is never used in this way. Also, there is no example in Jewish literature of the name "Babylon" ever being used as a code for Jerusalem.[87]

Moreover, preterists consistently quote Bible versions that portray the title on the harlot’s forehead as "Mystery Babylon the Great" (KJV, NIV).[88] They probably do so because this title conveys this meaning of non-literal, mystic, spiritual, or symbolic Babylon (11:8).[89] However, other versions read "mystery, Babylon the Great" (NASB) thus treating "mystery" in an appositional relationship to "name" rather than part of the harlot’s title. This latter translation favors viewing Babylon as a literal place rather than as a mere symbol and gives the impression that the title is simply a "mystery" or new truth.[90] The latter translation is preferred since John elsewhere always refers to Babylon as "Babylon the Great" rather than "Mystery Babylon the Great" (14:8, 16:19, 18:2, 10, 21)[91] and "the gender of both 'name' and 'mystery' are neuter while the gender of 'Babylon' is feminine." [92]

Second, if Babylon of Revelation 17-18 is really Jerusalem, then when were the prophecies predicting Babylon’s destruction fulfilled (Isa 13-14; Jer 50-51)?[93] It is common to also "preterize" these prophecies by arguing that they hyperbolically predict Babylon’s historic fall in 539 B.C.[94] However, it is difficult to similarly "preterize" the prediction of Babylon’s future found in Zechariah 5:5-11 since this prophecy was given in 519 B.C. (Zech 1:7) or 20 years after Babylon’s historic fall.

Third, the details of Revelation 17-18 bear little resemblance to first century Jerusalem. For example, Jerusalem did not sit on many waters (17:15), reign over the kings of the earth or even herself (17:18),[95] or resemble an economic power (18).[96] Furthermore, although the description of the harlot seems to communicate her heavy involvement with idolatry (" spiritual adultery," "unclean things," and "abominations" ) this is an odd description of first century Jerusalem in light of the fact that the city of that era was strictly monotheistic.[97] Also, how could Jerusalem be considered the "mother of harlots" or the source of all harlotry when harlotry existed (Gen 11:1-9)[98] long before the city of Jerusalem existed?[99] Thus, calling Jerusalem a daughter harlot rather than the "mother of harlots" seems a more appropriate designation.[100] Moreover, if the Babylon = Jerusalem hypothesis is correct then Jerusalem will never be rebuilt again (Rev 18:21). Yet, how can this be a description of Jerusalem when Scripture repeatedly speaks of this city’s return to prominence during the millennial reign (Isa 2:3; Zech 14:16; Rev 20:9)?[101] Finally, while the preterist attempts to argue that Babylon = Jerusalem based upon a few nebulous connections between Revelation 17-18 and Ezekiel 16,[102] he ignores the far more striking parallels between Revelation 17-18 and Jeremiah 50-51.[103]

Christ’s Thousand Year Reign (Rev 20:1-10)

Rather than understanding Rev 20:1-10 as describing the one thousand year earthly reign of Christ following His bodily return (premillennialism), Gentry sees these verses as speaking of a spiritual kingdom that began in the earthly ministry of Christ, was proved in the destruction of Jerusalem,[104] and progresses all the way until the Second Advent that is said to occur in 20:9 (postmillennialism). This spiritual kingdom also represents Christ’s new bride (Rev 21-22) that replaces harlotrous Israel (Rev 17-18).[105] Because Gentry believes that the millennium and the eternal state are spiritual realities that began in the first century and continue until the present day and beyond, by his own admission, he understands Revelation 20-22 more in the manner of an idealist than a preterist.[106] However, the assertion of a spiritualized millennium is built upon problematic assumptions.

First, the preterist ignores the chronological arrangement of Revelation’s last eight events. The repetition of the verb "I saw" in Revelation’s closing chapters yields the following chronology.[107]

| Order | Scripture | Description |

|

1 |

19:11-16 |

Second Advent |

|

2 |

19:17-18 |

Summoning of the birds of prey |

|

3 |

19:19-21 |

Destruction of Christ’s adversaries |

|

4 |

20:1-3 |

Satan’s confinement |

|

5 |

20:4-10 |

Satan’s release and defeat |

|

6 |

20:11 |

Great White Throne Judgment setting |

|

7 |

20:12-15 |

Sentencing to the lake of fire |

|

8 |

21:1-8 |

New Jerusalem |

The preterist ignores this chronology by placing Satan’s binding (Matt 12:28-29) and the believer’s resurrection before the events of Revelation 19:11-18, which supposedly represent the fall of Jerusalem. He has the same problem with his interpretation of the new bride (Rev 21-22). Since it is an alleged ongoing reality, he places it before Satan’s release and defeat (Rev 20:4-10) as well as the Great While Throne Judgment setting (Rev 20:11) and sentencing (Rev 20:12-15).

Second, the preterist must "deliteralize" the figure one thousand years that occurs six times in Revelation 20:1-10.[108] Yet this practice is questionable. When a specific number is used with the word "years" it always refers to a literal number throughout the entire New Testament.[109] Furthermore, although John is skilled at using indefinite concepts even within this same chapter, such as "a short time" (20:3), he instead gives a specific number when discussing the millennium’s length.[110] Thus, John could have just as easily used the expression "a long time" (Matt 25:19) if he wanted to communicate a general era rather than a concrete period of time.

While Revelation is a symbolic book not everything in the book is necessarily symbolic. A textual clue must be furnished before the interpreter has license to treat something symbolically (11:8; 17:18).[111] No such textual clue is apparent here regarding the millennium’s length. Thus, Thomas observes that, "no number in Revelation is verifiably a symbolic number." [112] Also, if 1000 is not meant to be interpreted literally, then the door suddenly opens for every other number in the Book of Revelation to also be construed non-literally, such as the 2 witnesses (Rev 11:3), 7000 people (Rev 11:13), 4 angels (Rev 7:1), 7 angels (Rev 8:6), and 144,000 Jews (Rev 7:4).[113]

Gentry’s citation of Psalm 50:10 to prove the symbolic nature of the phrase "the thousand years" [114] does little to bolster his argument since that context involves synonymous Hebrew parallelism. Thus, the phrase "cattle on a thousand hills" must be understood harmoniously with the preceding phrase "for every beast of the forest is mine." No similar parallelism is found involving the repetition of the phrase "the thousand years" in Revelation 20:1-10. Also, complaining that "only one place in all of Scripture limits Christ’s rule to a thousand years" [115] is unhelpful since the time limit actually appears six times in the chapter. Besides, how many times does God have to say something before it is taken seriously?

Third, while Gentry cites a series of celestial oriented passages as proof that the kingdom has begun (Eph 1:3; 2:6; Col 3:1-4),[116] Revelation is clear that the kingdom will take place "upon the earth" (Rev 1:6; 5:10). Also, Revelation nowhere portrays Christ as presently ruling from David’s throne but rather portrays Christ’s present position as emanating from the Father’s throne (Rev 12:5). In fact, decades after His Ascension,[117] Christ in Revelation 3:21 drew a sharp distinction between His present position on His Father’s celestial throne and His future, terrestrial Davidic Throne.[118] "Christ is here saying that, those who are spiritually victorious, will be rewarded (future tense of didomi) by joining Him in His earthly Messianic reign, just as He overcame (aorist tense) and sat down (aorist tense) with His Father on His throne." [119]

Fourth, regarding the two resurrections (Rev 20:4-5), Gentry says, "one is spiritual and present; the other is physical and future." [120] However, how can the first resurrection be spiritual (Rom 6:4-14; Eph 2:5-6; Col 3:1) when "resurrection" (anastasis) always refers to a physical resurrection in all of its New Testament occurrences?[121] Furthermore, how can the same verb "to come to life" (zaō) mean different things in consecutive verses?[122] Fifth, although Gentry associates Christ’s bodily return with the fiery judgment upon the rebels at the end of the millennium (20:9; 2 Thess 1:8),[123] the "verses contain no mention of a personal coming of Christ; they refer only to direct punishment from heaven..." [124]

The Eternal State and New Jerusalem (Rev 21-22)

Rather than understanding the final two chapters of the Apocalypse as the new creation that will follow the millennium (20:1-10) and final judgment (20:11-15), Gentry understands them as speaking of the new bride or the international church that replaces God’s previously destroyed unfaithful wife, racially based Israel.[125] Thus, Gentry sees Revelation 21-22 as beginning in the first century and extending into eternity.[126] In addition to the aforementioned chronological problems, Gentry must wildly allegorize these chapters in order to make them fit the present day.[127] Only by refusing to take the text at face value is it possible to argue that today there is no more Satan (Rev 20:10), sea (Rev 21:1), death, crying, pain (Rev 21:4), sun (Rev 22:5), moon (Rev 21:23), night (Rev 21:25), evil (Rev 21:27), or curse (Rev 22:23).[128] Such an allegorical approach is apparent in the way Gentry inconsistently interprets the word "sea" in Revelation 13:1 as a reference to the literal sea in between Patmos and Rome[129] while simultaneously interpreting the word "sea" in Revelation 21:1 as sin and internal discord.[130]

Gentry criticizes the literal view of the New Jerusalem on the grounds that it results in interpreting the city as reaching a height "1,200 miles higher than the space shuttle orbits." [131] However, this criticism reflects a uniformitarian perspective (2 Pet 3:3-7) that assumes that what is normative today will also be normative in the new creation. Thomas explains, "...the resources available to an infinite God to create such a city are beyond present comprehension. Far more materials are available to him than humans of the present era can possibly comprehend." [132]

Concluding Exhortation (Rev 22:10)

Preterists use the juxtaposition of the command given to Daniel to seal up the words of the vision (Dan 8:26; 12:4, 9) and the concluding command given to John to not seal up the words of the vision (22:10) to teach that the prophecy had to be fulfilled within John’s immediate lifespan.[133] However, this comparison involves reading more into these verses than what is actually there. "...John was not told to 'unseal the revelation he received.' Rather, he was told, 'Do not seal up the words of the prophecy of this book, for the time is near.' This does not mean that the prophecy was fulfilled in John’s day but that the words of the prophecy could be understood by those who read them in his day." [134]

Conclusion

In conclusion, the futurist interpretation of the Book of Revelation holds up under close scrutiny. The arguments relied upon by preterism, futurism’s closest rival, that the bulk of the book was fulfilled in the first century are specious and unconvincing. When examined closely, these arguments, far from making a convincing case for an A.D. 70 realization, actually end up favoring the futurist interpretation.

Bibliography

Barr, James. The Semantics of Biblical Language. London: Oxford University Press, 1961.

Beale, G. K. The Book of Revelation. New International Greek Testament Commentary, ed. I. Howard Marshall and Donald A. Hagner. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999.

Bullinger, E. W. The Apocalypse or "the Day of the Lord". Great Britain: Hollen Street, 1935. Reprint, London: Samuel Bagster & Sons, 1972.

Chilton, David. The Days of Vengeance: An Exposition of the Book of Revelation. Tyler, TX: Dominion Press, 1987.

Constable, Thomas L. "Notes on Numbers." Online: www.soniclight.com. Accessed 22 May 2006.

Couch, Mal. "Progressive Dispensationalism: Is Christ Now on the Throne of David?-Part I." Conservative Theological Journal 2, no. 4 (March 1998): 32-46.

Deere, Jack. "Premillennialism in Revelation 20:4-6." Bibliotheca Sacra 135 (January-March 1978): 58-73.

DeMar, Gary. Last Days Madness. 4th rev ed. Powder Springs, GA: American Vision, 1999.

________. End Times Fiction. Nashville, TN: Harvest House, 2001.

Dyer, Charles H. "Jeremiah." In Bible Knowledge Commentary, ed. John F. Walvoord and Roy B. Zuck. Colorado Springs, CO: Chariot Victor Publishing, 1983.

________. "The Identity of Babylon in Revelation 17-18 (Part 2)." Bibliotheca Sacra 144 (October-December 1987): 433-49.

__________. "Introduction to Ezekiel." Unpublished class notes in 304C Old Testament Prophets. Dallas Theological Seminary, Spring 2000.

Fruchtenbaum, Arnold G. Footsteps of the Messiah. rev ed. Tustin, CA: Ariel Ministries, 2003.

________. Hebrew Christianity: Its Theology, History, & Philosophy. Washington D.C.: Canon, 1974.

________. Israelology: The Missing Link in Systematic Theology. rev. ed. Tustin: Ariel Ministries, 1994.

Garland, Tony. A Testimony of Jesus Christ-Volume 1: A Commentary on the Book of Revelation. Camano Island, WA: SpiritAndTruth.org, 2004.

________. A Testimony of Jesus Christ-Volume 2: A Commentary on the Book of Revelation. Camano Island, WA: SpiritAndTruth.org, 2004.

Geisler, Norman L. "A Friendly Response to Hank Hanegraaff’s Book, The Last Disciple." Online: http://normangeisler.com/response-to-hanegraaffs-last-disciple/. Accessed 15 August 2018.

Gentry, Kenneth L. Before Jerusalem Fell. Tyler, TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1989.

________. He Shall Have Dominion. 2d and rev. ed. Tyler: TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1997.

________. "A Preterist View of Revelation." In Four Views on the Book of Revelation, ed. C. Marvin Pate. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1998.

________. The Beast of Revelation. Powder Springs, GA: American Vision, 2002.

Gregg, Steve, ed. Revelation: Four Views: A Parallel Commentary. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997.

Hanegraaff, Hank. The Apocalypse Code. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2007.

Hanegraaff, Hank, and Sigmund Brouwer. The Last Disciple. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 2004.

________. The Last Sacrifice. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 2005.

Hitchcock, Mark. The Second Coming of Babylon. Sisters, OR: Multnomah Publishers, 2003.

________. "A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation." Ph.D. diss., Dallas Theological Seminary, 2005.

Hitchcock, Mark, and Thomas Ice. The Truth Behind Left Behind. Sisters: OR: Multnomah, 2004.

Hoehner, Harold W. Chronological Aspects of the Life of Christ. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1977.

________. "Evidence from Revelation 20." In The Coming Millennial Kingdom, ed. Donald K. Campbell and Jeffrey L. Townsend. Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1997.

________. Ephesians: An Exegetical Commentary. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2002.

House, H. Wayne, and Thomas Ice. Dominion Theology: Blessing or Curse? Portland, OR: Multnomah, 1988.

Ice, Thomas. "Has Bible Prophecy Already Been Fulfilled? (Part 2)." . Conservative Theological Journal 4 (December 2000): 291-327.

Ice, Thomas, and Kenneth L. Gentry. The Great Tribulation: Past or Future? Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1999.

Johnson, S. Lewis. "Paul and the 'Israel of God': An Exegetical and Eschatological Case-Study." In Essays in Honor of J. Dwight Pentecost, ed. Stanley D. Toussaint and Charles H. Dyer. Chicago: Moody, 1986.

Morris, Henry. The Revelation Record. Wheaton, Ill: Tyndale, 1983.

Mounce, Robert H. The Book of Revelation. New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983.

Murphy, Frederick J. Early Judaism: The Exile to the Time of Jesus. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2002.

The NET Bible. Biblical Studies Press, 2001.

The NIV Study Bible. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1985.

Oepke, Albrecht. "Kalupto." In Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, ed. G. Kittel, trans. G.W. Bromiley. Grand Rapids, 1965.

Pate, C. Marvin. "A Progressive Dispensationalist View of Revelation." In Four Views on the Book of Revelation, ed. C. Marvin Pate. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1998.

Pentecost, J. Dwight. Things to Come: A Study in Biblical Eschatology. Findley, OH: Dunham Publishing Company, 1958.

________. "Daniel." In The Bible Knowledge Commentary, ed. John F. Walvoord and Roy B. Zuck. Colorado Springs, CO: Chariot Victor, 1985.

Pink, Arthur. The Antichrist. Swengel, PA: I. C. Herendeen, 1923.

Ramm, Bernard. Protestant Biblical Interpretation. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1970.

Robertson, Archibald Thomas. Word Pictures in the New Testament. 6 vols. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1933.

Ryrie, Charles C. Basic Theology. Wheaton: Victor Books, 1986.

________. The Ryrie Study Bible: New American Standard Bible. Chicago: Moody, 1995.

Smith, J. Ritchie. "The Date of the Apocalypse." Bibliotheca Sacra 45 (April-June 1888): 297-328.

Sproul, R. C. The Last Days According to Jesus. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1998.

Tenney, Merrill C. Interpreting Revelation. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1957.

Thomas, Robert L. Revelation 1 to 7: An Exegetical Commentary. Chicago: Moody Press, 1992.

________. Revelation 8 to 22: An Exegetical Commentary. Chicago: Moody Press, 1992.

________. "A Classical Dispensationalist View of Revelation." In Four Views on the Book of Revelation, ed. C. Marvin Pate. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1998.

________. Evangelical Hermeneutics: The New Versus the Old. Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2002.

Vine, W. E. Vine's Complete Expository Dictionary of the Old and New Testament Words. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1985.

Walvoord, John F. The Millennial Kingdom. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1959.

________. The Revelation of Jesus Christ. Chicago: Moody Press, 1966.

Woods, Andy. "Revelation 13 and the First Beast." In The End Times Controversy: The Second Coming under Attack, ed. Tim LaHaye and Thomas Ice. Eugene, OR: Harvest House, 2003.

Zuck, Roy. Basic Bible Interpretation: A Practical Guide to Discovering Biblical Truth. Colorado Springs: CO: Chariot Victor, 1991.

Endnotes

[1] Kenneth L. Gentry, Before Jerusalem Fell (Tyler, TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1989); idem, He Shall Have Dominion, 2d and rev. ed. (Tyler: TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1997); idem, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” in Four Views on the Book of Revelation, ed. C. Marvin Pate (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1998); R.C Sproul, The Last Days According to Jesus (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1998); Gary DeMar, Last Days Madness, 4th rev ed. (Powder Springs, GA: American Vision, 1999); idem, End Times Fiction (Nashville, TN: Harvest House, 2001); Hank Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2007); Hank Hanegraaff and Sigmund Brouwer, The Last Disciple (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 2004); idem, The Last Sacrifice (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 2005).

[2] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 86, 46, n.25..

[3] Gentry, He Shall Have Dominion, 407-34; idem, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 37-92.

[4] "Hermeneutics" may be defined as the science and art of biblical interpretation.

[5] Ryrie further explains that literal interpretation "...might also be called plain interpretation so that no one receives the mistaken notion that the literal principle rules out figures of speech." Charles C. Ryrie, Basic Theology (Wheaton: Victor Books, 1986), 86.

[6] Bernard Ramm, Protestant Biblical Interpretation (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1970), 89-92.

[7] Robert L. Thomas, Revelation 1 to 7: An Exegetical Commentary (Chicago: Moody Press, 1992), 38.

[8] Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code, 13-36.

[9] Merrill C. Tenney, Interpreting Revelation (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1957), 139, 142.

[10] Apocalyptic literature is an extra-biblical literary genre that flourished around the time of Revelation’s composition. The Book of Enoch, Apocalypse of Baruch, Book of Jubilees, Assumption of Moses, Psalms of Solomon, Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs, and Sibylline Oracles as well as Revelation are all considered to be part of this literary era. This genre is comprised of works sharing the following common cluster of characteristics: extensive use of symbolism, vision as the major means of revelation (Rev 1:10-11), angelic guides (Rev 1:1), activity of angels and demons (Rev 12:7-8), focus on the end of the current age and the inauguration of the age to come (Rev 1:3), urgent expectation of the end of earthly conditions in the immediate future (Rev 21:1), the end as a cosmic catastrophe, new salvation that is paradisal in character (Rev 21-22), manifestation of the kingdom of God (Rev 11:15), a mediator with royal functions (Rev 3:7), dualism with God and Satan as the leaders, spiritual order determining the flow of history, pessimism about man’s ability to change the course of events, periodization and determinism of human history (Rev 6:11), other worldly journeys (Rev 4:1-2), the catchword glory (Rev 4:11), and a final showdown between good and evil (Rev 19:11-21). The above citations from Revelation show that it has at least some affinities with these extra biblical works. This list was adapted from Frederick J. Murphy, Early Judaism: The Exile to the Time of Jesus (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2002), 130-33.

[11] Steve Gregg, ed., Revelation: Four Views: A Parallel Commentary (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1997), 11.

[12] This is a tactic that Gentry applies repeatedly in his survey of Revelation. See Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 38, 47, 56, 60, 64, 72, 81, 89.

[13] Thomas, Revelation 1 to 7: An Exegetical Commentary, 23-28.

[14] Adapted from Robert L. Thomas, Evangelical Hermeneutics: The New Versus the Old (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2002), 338. Oepke similarly notes, “[Revelation] has many affinities with literature to which we now refer [i.e. apocalyptic], though it cannot be simply classified with it.” Albrecht Oepke, “Kalupto,” in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, ed. G. Kittel, trans. G.W. Bromiley (Grand Rapids: 1965), 3:578.

[15] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 41-45.

[16] John F. Walvoord, The Revelation of Jesus Christ (Chicago: Moody Press, 1966), 35.

[17] Thomas Ice, “Has Bible Prophecy Already Been Fulfilled? (Part 2),” Conservative Theological Journal 4 (December 2000): 306.

[18] For a helpful survey of other views that futurists have adopted in an attempt to handle Revelation’s so called timing texts, see Mark Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation” (Ph.D. diss., Dallas Theological Seminary, 2005), 86-96.

[19] Thomas Ice and Kenneth L. Gentry, The Great Tribulation: Past or Future? (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1999), 162- 63. Here, I am not calling partial preterism unorthodox. I am simply saying that they must maintain an inconsistent position regarding their interpretation of Revelation’s “time texts” in order to remain orthodox.

[20] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 45-49.

[21] For more problems with this interpretation, see Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation,” 80-86.

[22] G. K. Beale, The Book of Revelation, New International Greek Testament Commentary, ed. I. Howard Marshall and Donald A. Hagner (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 26.

[23] James Barr, The Semantics of Biblical Language (London: Oxford University Press, 1961), 217-18.

[24] Gentry, Before Jerusalem Fell, 139-40; Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code, 110-11.

[25] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 86.

[26] Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation,” 147-48.

[27] Robert L. Thomas, “A Classical Dispensationalist View of Revelation,” in Four Views on the Book of Revelation, ed. C. Marvin Pate (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1998), 225. Preterists make much of the fact that the dictionary definition of oikoumene in 3:10 is “inhabited land.” However, this word can also have a global nuance in some contexts (Acts 17:31) and therefore need not be confined to a past local event. This universal understanding is buttressed through the accompanying adjective “whole.”

[28] Gregg, ed., Revelation: Four Views, a Parallel Commentary, 16.

[29] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 49.

[30] Ibid., 49, n. 33.

[31] Arnold G. Fruchtenbaum, Hebrew Christianity: Its Theology, History, & Philosophy (Washington D.C.: Canon, 1974), 41-44.

[32] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 51-52.

[33] Ibid., 51.

[34] Charles H. Dyer, "Introduction to Ezekiel," (unpublished class notes in 304C Old Testament Prophets, Dallas Theological Seminary, Spring 2000), 3.

[35] Thomas, “A Classical Dispensationalist View of Revelation,” 207.

[36] John F. Walvoord, The Millennial Kingdom (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1959), 149-52.

[37] Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code, 52-53, 178-79.

[38] See the helpful map showing what was promised in the Abrahamic Covenant in comparison to what was attained in the conquest in Thomas L. Constable, "Notes on Numbers," online: www.soniclight.com, accessed 22 May 2006, 99. Ryrie observes that the border to Egypt (4:21) is not the same thing as the river of Egypt (Gen 15:18). Charles C. Ryrie, The Ryrie Study Bible: New American Standard Bible (Chicago: Moody, 1995), 533.

[39] Arnold G. Fruchtenbaum, Israelology: The Missing Link in Systematic Theology, rev. ed. (Tustin: Ariel Ministries, 1994), 521-22, 631-32.

[40] Interpreters of all stripes recognized that the contents of Revelation 7 are largely given in order to answer the question posed at the end of the previous chapter, which is "Who can stand?" (Rev 6:17).

[41] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 57, n.49.

[42] Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code, 125-26.

[43] Ibid., 117.

[44] Mark Hitchcock and Thomas Ice, The Truth Behind Left Behind (Sisters: OR: Multnomah, 2004), 77.

[45] Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code, 125-27.

[46] Fruchtenbaum, Israelology: The Missing Link in Systematic Theology, 684-90. This rule holds true even with the oft cited Galatians 6:16. See S. Lewis Johnson, “Paul and the 'Israel of God': An Exegetical and Eschatological Case-Study,” in Essays in Honor of J. Dwight Pentecost, ed. Stanley D. Toussaint and Charles H. Dyer (Chicago: Moody, 1986), 181-96.

[47] Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code, 126.

[48] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 65-67.

[49] For a more detailed refutation of this position, see Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation,” 106-36.

[50] H. Wayne House and Thomas Ice, Dominion Theology: Blessing or Curse? (Portland, OR: Multnomah, 1988), 250.

[51] J. Ritchie Smith, “The Date of the Apocalypse,” Bibliotheca Sacra 45 (April-June 1888): 307-08.

[52] Gentry, He Shall Have Dominion, 421-22.

[53] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 66.

[54] The NIV Study Bible, (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1985), 1311.

[55] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 66.

[56] J. Dwight Pentecost, “Daniel,” in The Bible Knowledge Commentary, ed. John F. Walvoord and Roy B. Zuck (Colorado Springs, CO: Chariot Victor, 1985), 1335.

[57] Gentry, He Shall Have Dominion, 422.

[58] Thomas, “A Classical Dispensationalist View of Revelation,” 199.

[59] While most would understand the matriarch as Rachel, if the contents of Genesis 35-37 are given in chronological order, then the matriarch would have to be Leah since Rachel’s death is recorded in Genesis 35. Also, the reason that 37:9 only mentions eleven stars or tribes rather than twelve is because the twelfth star or tribe represents Joseph who is narrating the dream. He is the twelfth star that the other eleven stars bow down to.

[60] Thomas, “A Classical Dispensationalist View of Revelation,” 199.

[61] David Chilton, The Days of Vengeance: An Exposition of the Book of Revelation (Tyler, TX: Dominion Press, 1987), 309.

[62] Tony Garland, A Testimony of Jesus Christ-Volume 1: A Commentary on the Book of Revelation (Camano Island, WA: SpiritAndTruth.org, 2004), 482-83.

[63] Kenneth L. Gentry, The Beast of Revelation (Powder Springs, GA: American Vision, 2002).

[64] For a more extensive refutation of the Neronian hypothesis, see Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation,” 137-56; Andy Woods, “Revelation 13 and the First Beast,” in The End Times Controversy: The Second Coming under Attack, ed. Tim LaHaye and Thomas Ice (Eugene, OR: Harvest House, 2003), 237-50.

[65] Gentry, Before Jerusalem Fell, 163; Gentry, The Beast of Revelation, 181.

[66] Gentry, Before Jerusalem Fell, 209-12.

[67] Smith, “The Date of the Apocalypse,” 317.

[68] Robert H. Mounce, The Book of Revelation, New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983), 265; Smith, “The Date of the Apocalypse,” 318.

[69] Mounce, The Book of Revelation, 35.

[70] Beale, The Book of Revelation, 719.

[71] Ibid; Mounce, The Book of Revelation, 264, n.61.

[72] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 70.

[73] Harold W. Hoehner, Chronological Aspects of the Life of Christ (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1977), 115-39.

[74] Hitchcock and Ice, The Truth Behind Left Behind, 216-17.

[75] Robert L. Thomas, Revelation 8 to 22: An Exegetical Commentary (Chicago: Moody Press, 1992), 163.

[76] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 74.

[77] Barr, The Semantics of Biblical Language, 217-18.

[78] Josephus, Wars of the Jews 4. 11.5

[79] Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code, 118-24.

[80] Charles H. Dyer, “The Identity of Babylon in Revelation 17-18 (Part 2),” Bibliotheca Sacra 144 (October-December 1987): 434. Also, the harlot imagery (Rev 17:1, 5) need not automatically refer back to God’s accusations of Israel as an unfaithful harlot. Thomas notes that the angel describing the woman uses the term pornh (harlotry) rather than moiceia (adultery). The latter word is more restrictive “implying a previous marital relationship.” Although pornh can include adultery, it is broader. Thus, it is possible that the “woman represents all false religions of all time” rather than just the spiritual unfaithfulness of God’s covenant people Israel. Thomas, Revelation 8 to 22: An Exegetical Commentary, 283.

[81] Armageddon is an actual geographic area located in Northern Israel.

[82] Emphasis mine. A similar pattern is found in Galatians 4:24-25 where the text itself uses the word "allegorically" to explain that the city of Jerusalem is being figuratively used of Hagar, Mount Sinai, and the Old Covenant. These texts in no way deny Jerusalem as a literal city. Rather, they are simply saying that Jerusalem has a spiritual dimension in addition to being a literal city.

[83] Thomas, Revelation 8 to 22: An Exegetical Commentary, 206-07.

[84] Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation,” 177, n.3.

[85] Thomas, Revelation 8 to 22: An Exegetical Commentary, 307.

[86] Ibid., 206.

[87] Beale, The Book of Revelation, 25.

[88] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 77; Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code, 118.

[89] Archibald Thomas Robertson, Word Pictures in the New Testament, 6 vols. (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1933), 6:430.

[90] W. E. Vine, Vine's Complete Expository Dictionary of the Old and New Testament Words (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1985), 424; Harold W. Hoehner, Ephesians: An Exegetical Commentary (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2002), 428-34.

[91] Dyer, “The Identity of Babylon in Revelation 17-18 (Part 2),” 434-36; Walvoord, The Revelation of Jesus Christ, 246; Thomas, Revelation 8 to 22: An Exegetical Commentary, 289; Henry Morris, The Revelation Record (Wheaton, Ill: Tyndale, 1983), 324.

[92] The NET Bible, (Biblical Studies Press, 2001), 2336, n.2. Also, musthrion of Revelation 17:5 cannot be equated with “spiritually” (pneumatikws) of Revelation 11:8 to support the notion that Babylon of Revelation 17:5 deserves the same type of spiritual interpretation that is given to Jerusalem in Revelation 11:8 since “Musthrion is a noun, not an adverb like pneumatikws” and musthrion comes from a different root than pneumatikws. Thomas, Revelation 8 to 22: An Exegetical Commentary, 288-89.

[93] For an exposition of these prophecies demonstrating that they have never been fulfilled historically, see Dyer, “The Identity of Babylon in Revelation 17-18 (Part 2),” 443-49; Charles H. Dyer, “Jeremiah,” in Bible Knowledge Commentary, ed. John F. Walvoord and Roy B. Zuck (Colorado Springs, CO: Chariot Victor Publishing, 1983), 1199; Mark Hitchcock, The Second Coming of Babylon (Sisters, OR: Multnomah Publishers, 2003), 79-91; Morris, The Revelation Record, 348.

[94] Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code, 232-33. Arguing that these prophecies are simply hyperbolic is the only option for those who insist that they were fulfilled in 539 B.C. because they bear little resemblance to Babylon’s historic fall. This becomes apparent upon comparing the language of these prophecies with the historical record of Babylon’s fall as recorded in the writings of Herodotus, who wrote around 450 B.C. See Herodotus, Histories 1.191.

[95] Jerusalem was under the political control of Rome at the time John penned the Apocalypse.

[96] Hitchcock, “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation,” 177, n.3.

[97] Beale, The Book of Revelation, 885. First century Jews recognized idolatry had caused the Babylonian captivity. This recognition had the effect of curing the nation of that particular sin. Beale, The Book of Revelation, 887.

[98] Fruchtenbaum calls Babel “the mother of idolatry, for it was here that idolatry and false religion began (Genesis 11:1-9).” Arnold G. Fruchtenbaum, Footsteps of the Messiah, rev ed. (Tustin, CA: Ariel Ministries, 2003), 237-38.

[99] Jerusalem did not even fall into Jewish hands until the time of David (2 Sam 5) around 1004 B.C.

[100] Tony Garland, A Testimony of Jesus Christ-Volume 2: A Commentary on the Book of Revelation (Camano Island, WA: SpiritAndTruth.org, 2004), 203-4; E. W. Bullinger, The Apocalypse or "the Day of the Lord" (Great Britain: Hollen Street, 1935; reprint, London: Samuel Bagster & Sons, 1972), 506; Arthur Pink, The Antichrist (Swengel, PA: I. C. Herendeen, 1923), 258-59.

[101] C. Marvin Pate, “A Progressive Dispensationalist View of Revelation,” in Four Views on the Book of Revelation, ed. C. Marvin Pate (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1998), 169-70.

[102] Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code, 235.

[103] Both passages associate Babylon with a golden cup (Jer 51:7a; Rev 17:3-4; 18:6), dwelling on many waters (Jer 51:13; Rev 17:1), intoxicating the nations (Jer 51:7b; Rev 17:2), and having the same name (Jer 50:1; Rev 17:5; 18:10). Both passages analogize Babylon’s destruction to a stone sinking into the Euphrates (Jer 51:63-64; Rev 18:21) and depict Babylon’s destruction as sudden (Jer 51:8; Rev 18:8), caused by fire (Jer 51:30; Rev 17:16; 18:8), final (Jer 50:39; Rev 18:21), and deserved (Jer 50:29; Rev 18:6). Both passages describe the response to Babylon’s destruction in terms of God’s people fleeing (Jer 51:6, 45; Rev 18:4) and heaven rejoicing (Jer 51:48; Rev 18:20). Dyer, “The Identity of Babylon in Revelation 17-18 (Part 2),” 441-43.

[104] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 84.

[105] Ibid., 82-86.

[106] Ibid., 86; Gentry, He Shall Have Dominion, 426.

[107] Thomas, “A Classical Dispensationalist View of Revelation,” 204, 222; Thomas, Revelation 8 to 22: An Exegetical Commentary, 579-81.

[108] Gentry, He Shall Have Dominion, 347.

[109] Jack Deere, “Premillennialism in Revelation 20:4-6,”, Bibliotheca Sacra 135 (January-March 1978): 70.

[110] Harold W. Hoehner, “Evidence from Revelation 20,” in The Coming Millennial Kingdom, ed. Donald K. Campbell and Jeffrey L. Townsend (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1997), 249.

[111] Roy Zuck, Basic Bible Interpretation: A Practical Guide to Discovering Biblical Truth (Colorado Springs: CO: Chariot Victor, 1991), 242.

[112] Thomas, Revelation 8 to 22: An Exegetical Commentary, 408.

[113] Zuck, Basic Bible Interpretation: A Practical Guide to Discovering Biblical Truth, 244-45.

[114] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 82.

[115] Ibid.

[116] Ibid., 85.

[117] Even if the preterist early dating scenario is correct, Christ uttered these words over three decades after His Ascension. If the late date scenario is correct, then Christ made this statement six decades after His Ascension.

[118] Thomas, Revelation 1 to 7: An Exegetical Commentary, 325;Walvoord, The Revelation of Jesus Christ, 99. Bullinger, The Apocalypse or "the Day of the Lord", 209-10.

[119] Mal Couch, “Progressive Dispensationalism: Is Christ Now on the Throne of David?-Part I,” Conservative Theological Journal 2, no. 4 (March 1998): 43.

[120] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 85.

[121] The only possible exception to this rule is in Luke 2:34 where the word refers to a common rising.

[122] Thomas, Revelation 8 to 22: An Exegetical Commentary, 206.

[123] Gentry, He Shall Have Dominion, 431.

[124] Thomas, “A Classical Dispensationalist View of Revelation,” 205-6, n.50.

[125] Gentry, “A Preterist View of Revelation,” 89-90.

[126] Gentry, He Shall Have Dominion, 432.

[127] An allegorical approach is one that does not pay attention to what the text says but instead uses the text’s words as a basis for incorporating a higher spiritual meaning. For a discussion of weaknesses of the allegorical approach to Scripture, see J. Dwight Pentecost, Things to Come: A Study in Biblical Eschatology (Findley, OH: Dunham Publishing Company, 1958), 5-6.

[128] Ice and Gentry, The Great Tribulation: Past or Future?, 160.