The Messianic Interpretation of Genesis 3:15

Randall Price

Pre-Trib Research Center Annual Conference

Sheraton Grand Hotel, Irving, TX

December 11, 2019

וְאֵיבָה ׀ אָשִׁית בֵּינְךָ וּבֵ֣ין הָאִשָּׁה וּבֵין זַרְעֲךָ וּבֵ֣ין זַרְעָ֑הּ

הוּ֚א יְשׁוּפְךָ רֹ֔אשׁ וְאַתָּה תְּשׁוּפֶנּוּ עָקֵֽב׃ בראשית ג׳ ט״

“And I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your seed and her seed; He shall crush your head, and you shall crush his heel.” Genesis 3:15

Introduction

Following the Fall, the LORD confronted Adam and Eve about their guilt and responsibility for the Fall (Genesis 3:8-13) but judgment is pronounced first on the Serpent[1] The Serpent instigated Eve’s deception that led to Adam’s willful decision to sin (Genesis 3:14-15; cf. 1 Timothy 2:4). Within this pronouncement of judgment on the Serpent is a prophecy concerning the conflict that would exist between the woman and the Serpent and between their respective "seed" until a climax was reached in which the woman's "seed" would crush the Serpent's head, despite the Serpent dealing a crushing blow to her seed's heel (Genesis 3:15). Because the Hebrew term אֵיבָה (‘eba) is always used of “enmity” between moral agents (Numbers 35:21-22; Ezekiel 25:15; 35:5) and who in this context are the progenitors of future historical figures, this verse has been traditionally interpreted as the conflict between Satan and the Savior resulting in the triumph of salvation. For this reason it has been called the “Gospel in the Garden” or the Protoevangelium ("first gospel"). As such, it has been said that “This is the root idea, of which all others are but shoots and branches and fruit … it is the beginning of the circular rings that mark the several periods of growth of the beautiful tree which was planted in the paradise of God.”[2] Although the earliest interpretation of this text was messianic, modern scholarship, including evangelical scholarship, has departed from seeing this as nothing more than the etiology of mankind’s fear of snakes or as an allegory of the human struggle between good and evil.[3] “However, it is understood,” writes the authors of Jesus the Messiah, “- it is not an explicitly messianic text.”[4] Yet, these same authors admit “In many ways, Genesis 3:15 represents a litmus test to one’s hermeneutical approach to the interpretation of messianic prophecy in the Hebrew Scriptures.”[5]

Victor Hamilton has emphatically stated, “I believe that any reflection on Genesis 3:15 that fails to underscore the messianic emphasis of the verse is guilty of a serious exegetical error.”[6] I would be so bold to say that Genesis 3:15 does not simply have a messianic emphasis, but it is the messianic prophecy, since all of the messianic predictions that are progressively revealed in the Old Testament have some point of reference with this initial prophecy. While one could have a messianic emphasis via an allegorical interpretation, I will argue that Genesis 3:15 is a direct (explicit) messianic prophecy with an eschatological focus and that this interpretation is supported by Hebrew grammar, the literary context, inner and inter-biblical interpretation, the New Testament and biblical theology.

- Hebrew Grammar Supports a Messianic Interpretation

The Hebrew text of Genesis 3:15 appears to be free of textual variants. The oldest extant fragments of the text are from a cave at Wadi Murabba’at (early second-century B.C.) with two other fragments (1Q1Gen; 4QGenk) coming from caves at Qumran. The text they witness to is identical to our present Masoretic Text. However, the problem has not been with the text, but its interpretation. Even though early Jewish targumim (Aramaic paraphrases of the Hebrew Scriptures), such as Targum Yerushalmi, refer this passage to "the days of the King, Messiah," and Rabbi Yohanan uttered “Every prophet prophesied only for the days of the Messiah” (b. Ber. 34b),” it has been the trend in the academy to distance itself from messianic interpretation and especially the traditional interpretation of Genesis 3:15. For example, the NET Bible, the product of evangelical academics, once stated: “Many Christian theologians (going back to Irenaeus) understand v. 15 as the so-called protevangelium, supposedly prophesying Christ’s victory over Satan. . . . In this allegorical approach, the woman’s offspring is initially Cain, then the whole human race, and ultimately Jesus Christ, the offspring (Heb “seed”) of the woman (see Gal 4:4) … However, the grammatical structure of Gn 3:15b does not suggest this view.”[7] Let us examine this claim for ourselves.

Single or Collective “Seed”?

The first grammatical issue to be resolved in Genesis 3:15 is to determine the precise referent of the "seed" of the woman. The Hebrew word translated "seed" or "offspring" (זרע) is grammatically singular but can have either have a singular or plural referent. Therefore, while not properly a collective noun, because it does not always refer to a group, it can have a collective sense when referring to an individual’s line (i.e., descendants). This inherent flexibility in meaning can be seen in Isaiah 6:13 where even though the collective “seed,” the Davidic dynasty has been felled, there remains the singular “holy seed” (זֶרַע קֹ֖דֶשׁ) to fulfill the messianic promise (Genesis 3:15). This ambiguity allows for the interpretation that it is the offspring of the woman collectively (human posterity) who will defeat the serpent, not an individual (i.e., the Messiah). That is to say, the word זרע, zera‘ (‘seed’) is taken as a collective, and the pronoun הוא hû’ is a collective masculine singular to match its antecedent zer‘āh (‘her seed’) and is better rendered “they.”[8] Thus, we read in the Jewish Publication Society’s version of the Tanakh: “I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; They shall strike at your head, and you shall strike at their heel.” This has become the accepted view in academic circles because it is thought only a collective understanding of זרע zera‘ and הוא hû’is syntactically possible.[9]

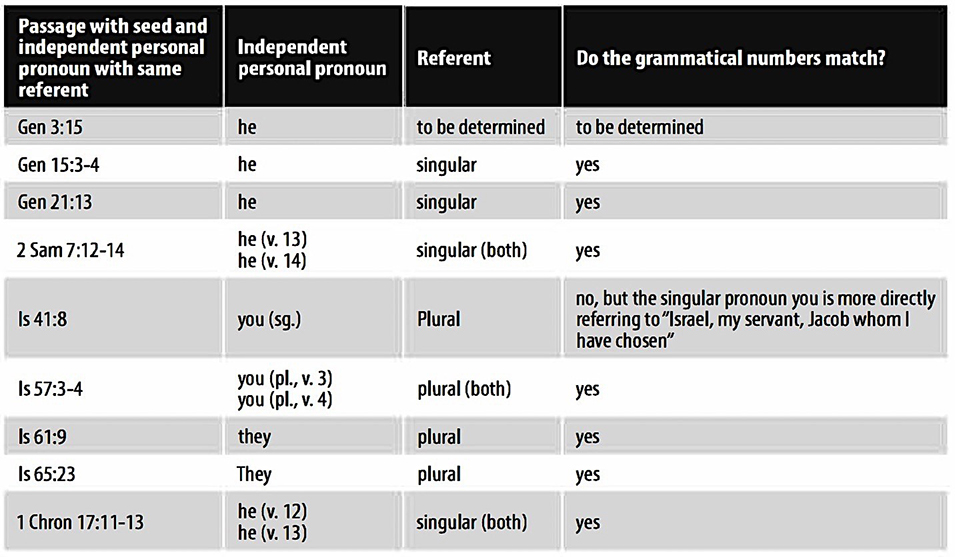

While the term may have flexibility, it needs to be examined throughout the Bible to see when and where this applies. Jack Collins did an empirical study of how Biblical Hebrew used its pronouns and verb inflections when they are associated with זרע zera‘, “seed,” when it has the nuance “offspring.” His data showed that when a biblical author has a collective sense for “seed” in mind that he consistently uses plural pronouns and verbal forms. By contrast, when an individual is in view, he uses singular pronouns and verbal forms. Kevin Chen cites some examples that use independent personal pronouns whose grammatical number (i.e., singular or plural) corresponds to whether the referent of “seed” is singular or plural (see chart below).[10]

The use of seed with independent personal pronouns

These parallels demonstrate that a singular independent personal pronoun is normally used to refer to an individual seed, not to a collective seed and argues in favor of interpreting the woman’s “seed” as an individual in Genesis 3:15. This would read as God’s threat to the snake (or the power behind it) of an individual who will engage it in combat and win. Chen observes, “the only way for a both-and is for "her seed" to be collective, but then it would not be the referent of "he" because "he" must refer only to an individual. In that case, the pronoun he would not have a proper referent in the preceding context. This is not the way pronouns function typically, nor does it cohere with Messianic passages that use the word seed.”[11]

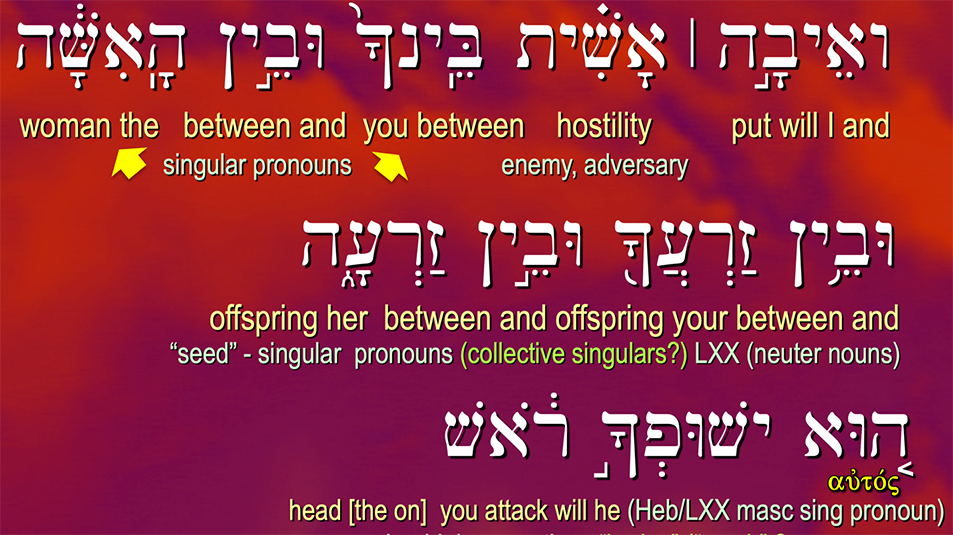

This introduces the second grammatical issue of how to interpret the masculine singular pronoun הוא, hû’ (“he”) in remainder of the verse. If the first half of the passage has a collective sense of the descendants of the woman versus those of the Serpent (rebellious seed versus righteous seed), why would there be a shift to an individual in the second half? However, the explicit use here of the singular independent personal pronoun to refer to the woman’s seed requires that an individual seed is to be understood. This can be seen in the LXX where its translators used αὐτός, autos (“he”), masculine, even though the antecedant σπέρματος, spermatos (“seed”) is neuter. One might have expected grammatical agreement: αυτό, auto (“it”) instead of αὐτός, autos (“he”), for though the Hebrew independent personal pronoun הוא, hû’ (“he”) occurs more than 100X, this is the only instance in which the LXX translates literally with αὐτός, autos instead of the neuter required by the Greek idiom (see chart below):

The best explanation for this grammatical mismatch in gender between pronoun and antecedent is that the LXX translator saw this as a prophecy of a specific individual and understood the Hebrew grammar to connote a messianic interpretation. Collins argues this point saying, “it becomes clear that, on the syntactical level, the singular pronoun הוא hû’ in Genesis 3:15 is quite consistent with the pattern where a single individual is in view. In fact, since the subject pronouns are not normally necessary for the meaning, we might wonder if the singular הוא hû’ in Genesis 3:15 is used precisely in order to make it plain that an individual is being promised, who will win a victory over the snake at cost to himself. The evidence of the Greek translators makes it beyond question that the translator of Genesis 3:15 meant to convey that an individual was promised; this study indicates that his interpretation is consistent with Hebrew syntax elsewhere in the Bible.”[12] It should be further noted, as will be discussed under inner-biblical usage, that other texts not only use the singular pronoun הוא (“he”) to refer to an individual seed but contain related content that argues for an intentional intertextual connection to Genesis 3:15.

- Literary Context Supports a Messianic Interpretation

As Seth Postell observes: “Context is king. This axiom expresses a foundational rule in biblical interpretation. This axiom is crucial for interpreting a verse that has all the appearance of being programmatic for the ensuing plot of the book as a whole.”[13] Considering only the early section of Genesis Steve Kempf has argued that Genesis 3 is a coherent discourse with its climax at vss. 14-19, which has a relation to ‘the “spread of sin” theme in the macrostructure of Genesis 1-11.[14] He observes special grammatical signals that mark Genesis 3:14-19 as the grammatical peak of the narrative discourse in Genesis 2-3.[15] John Sailhamer expands this to the greater context asking, “Who is the ‘seed’ of the woman?” and then stating “The purpose of this verse is not to answer that question but to raise it. The remainder of the book of Genesis and the Pentateuch gives the author’s answer.”[16] If this is the case, then despite the tragedy of deception and discipline, Genesis 3:15 is a word of hope and a promise of deliverance. In Genesis 1-2 Adam served as a king-priest in a prototypical Sanctuary and as God’s representative for the human race he was to populate the earth and rule (Genesis 1:26-28).[17]

This is also seen in a literary irony wherein Eve, even in her fallen state, will ultimately bring forth the One who will redeem her sin and reverse the curse. Moreover, the union of Eve with her husband will result in the production of an Heir who, in the end, will destroy the one who deceived her and after her the whole world (Rev. 12:9; 13:14, cf. 2 Jn. 7).[18] There is also judgment for the woman. Giving birth to the saving seed will be painful (3:16a); and her relationship with her husband, which is necessary for the seed to be born, will be strained (3:16b). Nevertheless, the “seed” from the “woman” (not the woman and the man), will be the agent of her future salvation. And it is the woman whom the man names חַוָּה )Chavvah), a wordplay on the Hebrew word for “life” (הַי), because not only will she produce life, but that life (i.e., the promised “seed”) will restore the life that has been lost as a result of the Fall. There may be an echo of this in 1 Timothy 2:15 where in the context of comparing Eve and her experience in the Garden to the women in Ephesus, Paul writes σωθήσεται (‘she will be saved”) in the future, and that “through childbearing” (δὲ διὰ τῆς τεκνογονίας). As Eve would be saved from the penalty of the Fall through her future seed, so the Ephesian women would be saved from the judgment in the Fall (namely subordination due to deception) through having children that can be taught.

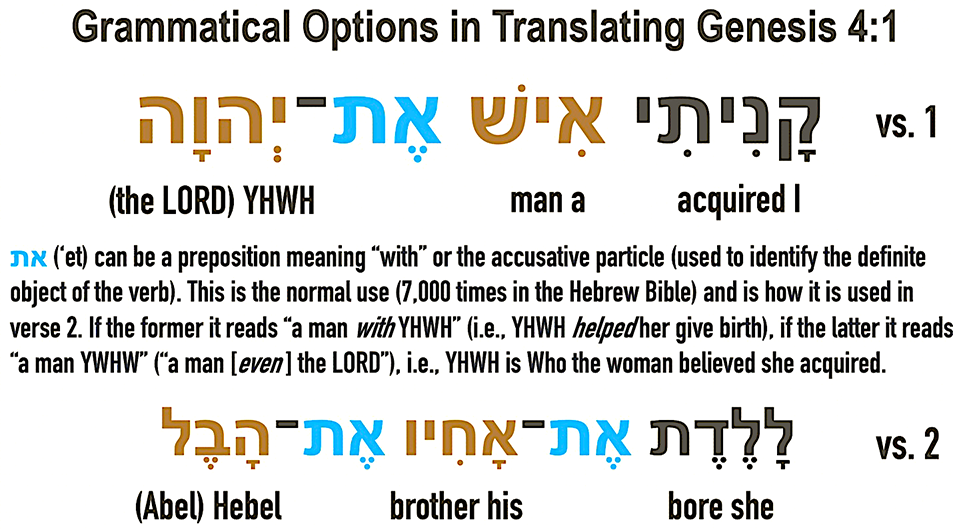

If Genesis 3:15 contained the promise of a savior/deliverer who would end enmity and reverse the curse, it would be expected that some reflection of this would be present elsewhere in the text. In the verses following vs. 15, God has announced that the woman will bring forth children in pain (vs. 16), that the ground will be cursed requiring painful labor (vss. 17-19), that the woman would be given a meaningful name, Chavah (“life”), vs. 20, clothed by God (implying forgiveness of their sin, since the skins used for their garments cost the life of an animal), vs. 21, and to prevent the perpetuation of man in a sinful state, God drove them out of Eden (vss. 22-24). In this context, it could be assumed that what was on Adam and Eve’s minds was how long they would be exiled and experience pain until deliverance was effected. After all, if God had restored them spiritually, why not physically? The solution that had been offered was the “seed of the woman,” so again, it may be assumed that they understood childbearing to be linked to their future redemption and restoration. If we come to the next verse (Genesis 4:1) with this understanding, we have a basis for interpreting a traditionally difficult text in a way that fits the context and supports a messianic interpretation of Genesis 3:15.

The Hebrew text reads: וְהָ֣אָדָם יָדַע אֶת־חַוָּ֣ה אִשְׁתּ֑וֹ וַתַּהַר וַתֵּ֣לֶד אֶת־קַיִן וַתֹּאמֶר קָנִיתִי אִ֖ישׁ אֶת־יְהוָֽה׃ (“Now the man had relations with his wife Chavah/Eve, and she conceived and gave birth to Qayin/Cain, and she said, ‘I have gotten a man: ‘Adonai/the LORD’”). The Hebrew text allows for two possible (the only two possible among all uses) of options for understanding the term את (‘et) as a preposition meaning “with” or the accusative particle (used to identify the definite object of the verb), as seen in the chart below:

The normal use (7,000 times in the Hebrew Bible) is as an accusative marker for the direct object and this is how it is used in the very next verse (verse 2), which is parallel in form to verse 1. If the former option of the preposition is adopted, the text will be translated “a man with (or from, as the KJV) YHWH.” Usually translations smooth out this idea by supplying the phrase “with the help of the LORD,” implying that in some way YHWH helped her to give birth. If the verse is translated with את (‘et) having its normal use it would be translated: “a man: YWHW” (or “a man [even ] the LORD”), implying YHWH (in bodily form) is Who the woman believed she acquired. The first view is a non-messianic one, the second messianic.

As might be expected, the messianic view has been largely rejected out-of-hand due to the theological difficulties involved. The Jewish perspective on the translation appears conflicted. The earliest Jewish view is that preserved in the Jewish Aramaic paraphrase of the Hebrew text known as the Targum (ca. 1 B.C.). In Targum Onkelos we read: “I have acquired a man קדם (qadam, “before”) Hashem.” Rabbinic commentators took this either as the idea that Cain was to perform service before the LORD” or that qadam = “with” and the thought was of a partnership with God as co-creators. This is similar to Rashi’s understanding: “I have acquired a man with Hashem, i.e., my husband and I have partnered with Him in bringing a child into the world.”[19] This may have been the understanding of the LXX translators who rendered the Hebrew text as ἐκτησάμην ἄνθρωπον διὰ τοῦ θεοῦ (“I have acquired a man through God”). However, in the Jerusalem Targum we have another view: “I have gotten a man: the angel of the LORD,” and similarly in Targum Pseudo-Jonathan: “I have gotten for a man the angel of the LORD.” A hundred years later in the second-century A.D., it would seem that there was a simplier solution to the problem. In a discussion between Rabbi Ishmael and Rabbi Akiba, the former asked the latter the reason for the ‘et written here and Akiba replied: “If it is said, ‘I have gotten a man, the LORD,’ it would have been very difficult to interpret. Hence, ‘et, ‘with the help of the LORD is required.’”[20] The early Protestant view may be seen in Martin Luther’s translation and comment: “’I have the man, the Lord.’ This properly is the meaning of the Hebrew original.”[21] In a similar manner the NET Bible’s notes disparage a messianic view of this verse stating rather bluntly: “This fanciful suggestion is based on a questionable allegorical interpretation of Genesis 3:15.”[22]

In seeking to understand what this verse means, Waltke reminds us that “The first responsibility is that we limit ourselves to the original historical situation. In this case, the meaning of the “seed” would be restricted to what Adam and Eve understood its meaning to be. Probably Eve at first thought Cain fulfilled the promise, but when he proved to be a murderer, she probably replaced Cain with Seth (Genesis 4:1-25).”[23] Waltke is correct concerning Eve’s initial hope that her first-born son would be the incarnate Savior. Eve, with her husband, had known the LORD in human form (theophany), walking with them in the Garden and searching for them after the Fall (Genesis 3:8-9). If God was to save them and salvation was to be through her seed, then God would come through that seed. However, she probably did not have to wait until Cain grew up and committed murder to change her mind. As Cain grew and fallen conditions remained the same, Eve understood that he was not a savior, much less the Savior. It is probable that this disillusionment and that her life would continue under the curse, caused her to name her second-born הָבֶל Hebel (Abel), a term that describes the transitory and unsatisfying experience of mankind in a fallen world.[24] In Ecclesiastes at the beginning of Solomon’s discourse as well as at the conclusion of pivotal discussions he concludes with the words הַכֹּ֛ל הֶ֖בֶל (hakol hebel, “all is vanity”). Paul alludes to this concept in Romans 8:20 using the LXX’s term for הָ֑בֶל (ματαιότητι, “futility”) and connects the end of this condition, a return of Creation to Paradise during the Millennium, with the full redemption of the sons of God (vss. 19-22). Walt Kaiser says, “If this suggestion is correct, then Eve understood that the promised male descendant of human descent would be, in some way, divine, ‘the LORD.’ If so, then Eve’s instincts about the coming Messiah were correct, but her timing was way off!”[25]

Genesis 4 also helps us to define in context who or what is the seed” of the Serpent” and who is the “seed of the woman.” Seth Postell explains:

In light of Gn 4, it becomes clear that the “seed” of the serpent” is not referring to literal snakes (contra the etiological interpretation of Gn 3:15). Rather, the close parallels between the fates of the serpent and Cain, followed by Cain’s genealogy in chap. 4, suggests that the author of Genesis wants us to understand the serpent’s “seed” metaphorically. The serpent’s seed are not to identified by physical progeny since Cain is also a child of Eve. Rather, the serpent’s seed must be identified by its actions, in this case, murder. The identification of Seth as a seed appointed by God in Gn 4:25 further suggests that divine election is crucial for identifying the “seed of the woman.” In this we also find a clue as to the identity of the serpent. The serpent stands as a parent-creature in a metaphorical line of evildoers who oppose God’s purposes for humanity and who war against a divinely appointed seed.[26]

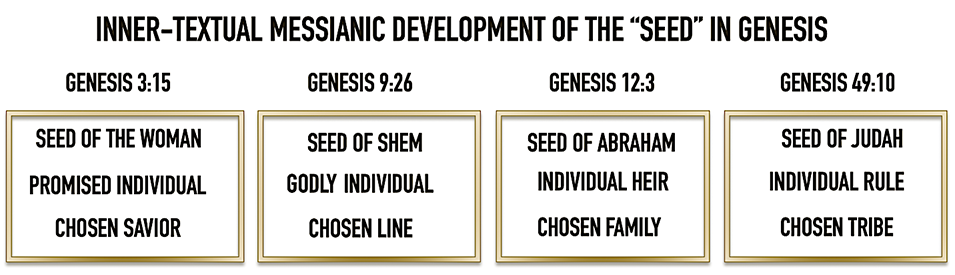

Finally, in the context of Genesis 1-11, which is a plot setter for the rest of the Torah, Genesis 3:15 is the plot in macrocosom. It contains all of the essential elements and themes that reveal the story line must move toward a resolution with the chosen seed ultimately triumphing to restore God’s original blessing to mankind. Adam and Eve were to subdue the land and rule for God over its creatures, but the Serpent effected their disobedience and they were exiled from Eden to eventually find themselves in Babylon (Genesis 11:9; Genesis 15:7a; cf. Isaiah 13:19) . From there God chose Abraham to enter a new Land where God’s promise could be fulfilled (Genesis 112:1-3; 15:18), but the same enemies from the evil one continued to oppose this purpose (Canaanites, etc.) and the struggle continued. The one constant was the “seed” of the woman, the promised Messiah, who despite being attacked kept moving forward from a family to a tribe to a dynasty to an advent. This will become clearer as we look at the inner-biblical interpretation.

- Inner-biblical Usage Supports a Messianic Interpretation.

The use of the Old Testament in the Old Testament reveals a complex and intentional use of earlier themes and texts to continue and develop the messianic message. While earlier interpreters did not have as much information as later interpreters, they were not ignorant of the information they did have and of its messianic significance. John Sailhamer writes, “I believe the messianic thrust of the OT was the whole reason the books of the Hebrew Bible were written. In other words, the Hebrew Bible was not written as the national literature of Israel. It probably also was not written to the nation of Israel as such. It was rather written, in my opinion, as the expression of the deep-seated messianic hope of a small group of faithful prophets and their followers”[27] With this understanding, the translators of the messianic Tree of Life Version (TLV), state: “Messiah Yeshua’s sacrificial death was not the start of a new religion, but the fulfillment of the covenant that has traveled through time from the seed promised to Eve all the way to the seed sown in Miriam’s womb.”[28]

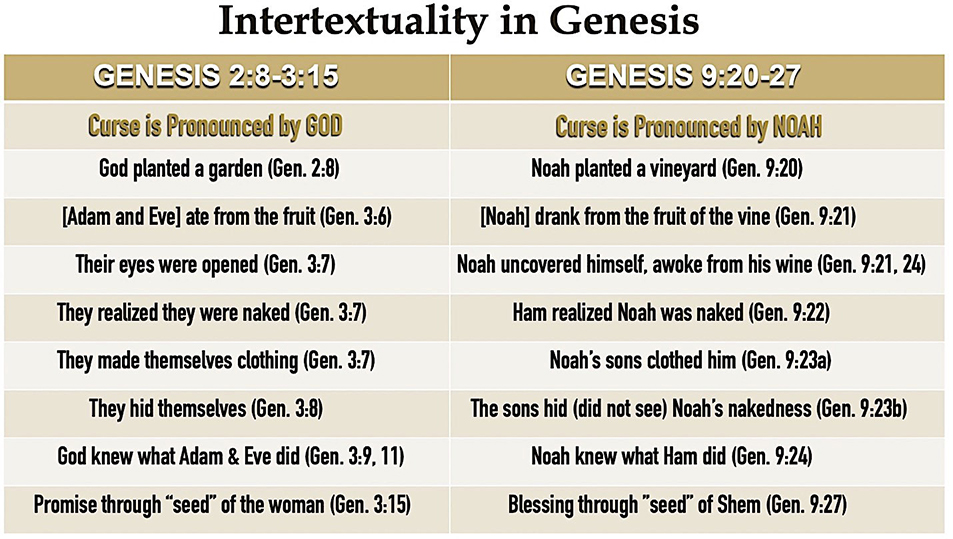

Once we are sensitive to literary themes that produce literary seams, repetition and word play, and other types of allusions and intertextual links, we observe the compositional strategy of the Old Testament is shaped by Genesis 3:15. These are the LORD’s words given within a judgment context to reveal the future plan of redemption and restoration of mankind and the Creation itself. As an eschatological text it projects its themes forward to be built upon by later inspired authors, whose words themselves have been shaped by the Spirit Who understands how these links should connect to progressively unveil the messianic program. As an example, consider the literary parallels between the judgment accounts in Genesis 3:15-24 and 9:23-27. See chart below:[29]

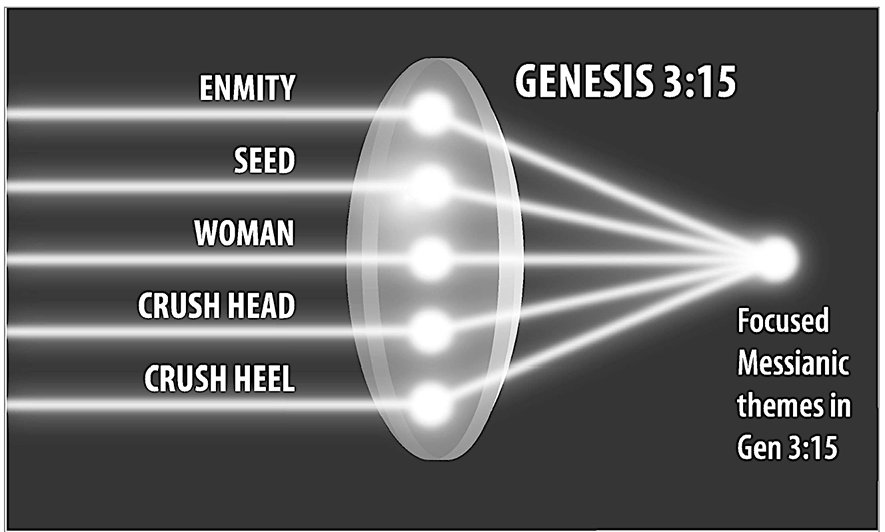

Here we see a pattern that requires us to look deeper into the purpose of the story. Adam and Noah both had three sons who were involved in their fathers’ “fall.” One fall is immediately after Creation and the other immediately after the Flood. The basic story is of human sin and divine judgment, but both accounts end with a promise of salvation in a coming ‘seed.” The seed of the woman in Genesis 3:15 will bring the promised blessing and despite the continued conflict within the fallen world, and the seed of Noah, Shem, will be the promised seed (Genesis 9:27) through whom blessing will come to Abraham and through him as a believer (Genesis 15:6) to the world (Genesis 12:3). As God’s first words to sinners, Genesis 3:15 introduces the messianic hope and combines important messianic themes: enmity with the Serpent, the promise of seed, the central role of a woman, the crushing of the enemy’s head, and the attack on the Promised Seed’s heel. Chen says that these themes (including some from the preceding context) are intentionally linked to this verse so that Genesis 3:15 serves as a "lens" that then focuses select messianic wavelengths from the overall spectrum (see below).

Five focused messianic themes based on the text of Genesis 3:15

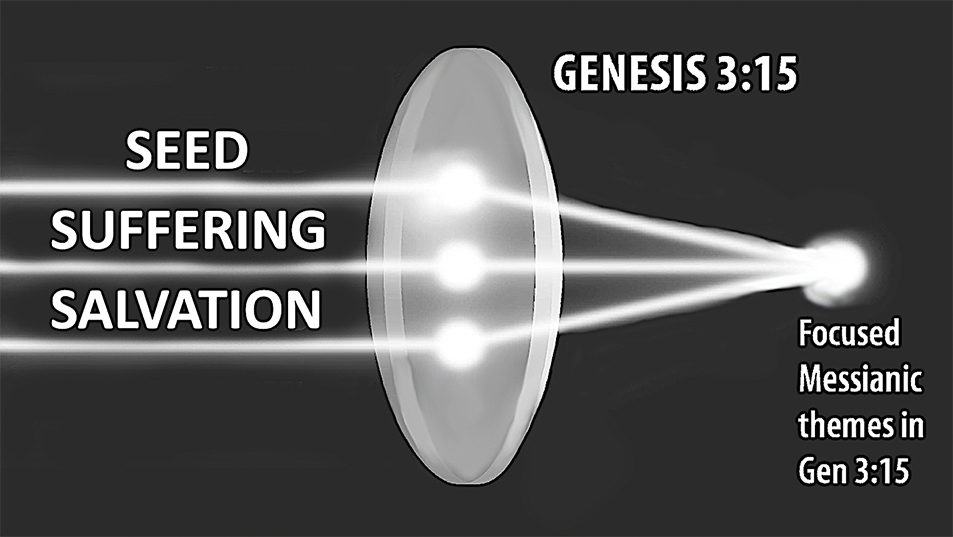

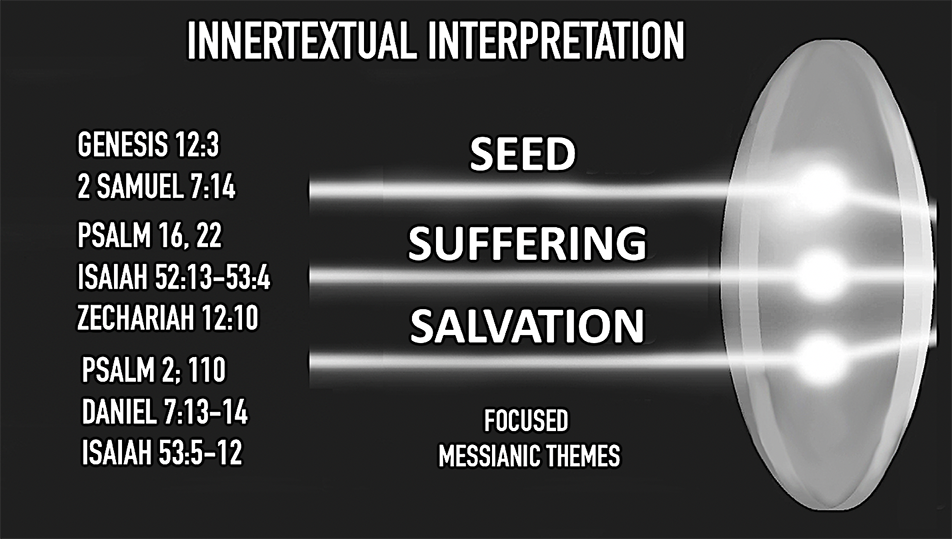

I have categorized these textual themes as the “seed,” “suffering,” and “salvation” (see chart below). The theme of the “seed” includes the woman who produces the seed and encompasses the Abrahamic and Davidic covenants, the theme of “suffering” includes the results of the enmity that leads to persecution and affliction of the seed with its climax in the crushing of the heel of the seed. This encompasses the suffering Servant through the messianic woes of the Tribulation. The theme of “salvation” includes YHWH’s acts of salvation on behalf of His People (physical and spiritual) climaxing in the fulfillment of the crushing of the head of the enemy, leading to an end of suffering and the redemption and restoration of the seed in the Millennial Kingdom. Of course, the repetition of key terms such as “seed” and the concept of “crushing the head” will help identify texts that link to Genesis 3:15, but these broader themes enable us to see additional intertextual and inner-biblical connections inspired by the source text.

Categorized focused messianic themes in Genesis 3:15

The Seed Theme

The promise of a seed was passed to Abraham (Genesis 12:7). Although he was predicted to have a multitude of seeds (collective sense), Genesis 12:2; 15:5, he was also told he would have a singular seed who as his heir (Genesis 15:3-4), “one who will go out from your loins [ אשר יצא ממעיך i.e., a seed], would alone continue the covenant and its blessings (Genesis 17:21). As in Genesis 3:15, this "seed" is referred to by the LORD in direct speech using the singular pronoun הוא hû (“he”). To these promises were added in Genesis 22:17 the promise of possessing (through conquest) the Chosen People’s enemies (אֹיְבָיו from same root as “enmity” in Genesis 3:15). As we move the seed theme toward a royal setting, we find the same wording used of Abraham’s direct heir used for the promise of God to David אֲשֶׁ֥ר יֵצֵ֖א מִמֵּעֶ֑יךָ (“who will go out from your loins”), 2 Samuel 7:12. Interestingly, Collins discovered in his empirical study of how Biblical Hebrew used its pronouns and verb inflections when associated with zera‘, that the clearest syntactic parallel to Genesis 3:15 is the next verse, 2 Samuel 7:13, where David’s promised offspring (zera‘, vs. 12) is identified as הוא hû (“he”) [who] “will build a house for My name” ה֥וּא יִבְנֶה־בַּ֖יִת לִשְׁמִ֑י. Here the antecendant pronoun must refer to an individual and the informed reader would see the connection with both the individual covenant seed of Abraham and the singular seed of Genesis 3:15. How is this messianic? While the reference to a Temple -builder seems to require Solomon, the promise is of a descendant “after you” (in context after your death) and the Chronicler apparently interpreted this of David’s greater son, the Messiah. In 1 Chronicles 17:12-14 he writes: “He shall build for Me a house, and I will establish his throne forever. I will be his father, and he shall be My son; and I will not take My lovingkindness away from him, as I took it from him who was before you. But I will settle him in My house and in My kingdom forever, and his throne shall be established forever” (1 Chronicles 17:12–14). This forever son has not only a forever Kingdom, but a position within God’s house (the Temple). No other figure than the Messiah is called Son” in relation to God and also granted an unending kingdom (Daniel 7:13-14, 18; cf. 2:44). Solomon was from the Tribe of Judah and only those from the Tribe of Levi were permitted to enter the Temple. The only One in the line of David Who is said to have a position in the Temple is the Messiah (Isaiah 2:2-4; Zechariah 6:11-13; Malachi 3:1; Ezekiel 37:25-28; 43:6-7). In Zechariah 6:13 the same individual pronoun appears with respect to one who is a Temple-building king but especially a messianic priestking. The wording of Genesis 3:15 properly prepared the reader to connect the individual with the Davidic line and the everlasting nature of the promise of rule, seen as a result of conquering the enemy (2 Samuel 7:1) and finally all enemies (Daniel 2:44). There are also many lexical, syntactic, and thematic connections between the Abrahamic and Davidic covenants. Chen lists these as as a great name (Genesis 12:2; 2 Sam 7:9), nationhood (Genesis 12:2; 2 Samuel 7:10), Land (Genesis 12:7; 2 Samuel 7:10), worldwide blessing (Genesis 12:3; Psalm 72:17), kingship (Genesis 27:29; 2 Samuel 7:12-16), and eternality (Genesis 17:7; 2 Samuel 23:5). These commonalities suggest that the two covenants along with the original promise of Genesis 3:15 are fulfilled by the same “seed” (cf. Matthew 1:1).[30] I have summarized this for the Book of Genesis in the chart below:

The Suffering Theme

The expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden thrust them into diaspora in an alien and hostile world. David Dorsey has described Adam and Eve as “driven from the garden … forced to till the soil to get food, separated from the source of perpetual life (and health),” while Cain was “driven out, doomed to wander forever with no permanent home, not even able to till the soil for his food and hounded by death (would-be killers) wherever he goes.”[31]

The predicted enmity would also produce suffering for the seed of the woman collectively and individually through the crushing that takes place between the Serpent and the Savior. With respect to the attack on the individual “seed” Satan has repeatedly tried to derail the seed promise and destroy the messianic lineage. Examples of this are Cain’s fratricide/homicide (Genesis 4:8-10), the infiltration of human race (Genesis 6:2-4), corruption of the seed of Abraham through Canaanite intermarriage (Genesis 24:3, 7; 27:46; 28:1, 6; 36:2; 38:2-3, 14), infanticides of Hebrew newborn males under Pharaoh (Exodus 1:22) and Herod (Matthew 2:16), and genocide under Haman (Esther 3:6).

Examples of suffering texts echoing Genesis 3:15 are seen throughout the Old Testament: Psalm 72:4: “May he vindicate the afflicted of the people, save the children of the needy, and crush the oppressor.” Jeremiah 17:18: “Let those who persecute me be put to shame, but as for me, let me not be put to shame; Let them be dismayed, but let me not be dismayed. Bring on them a day of disaster and crush them with twofold destruction!” This theme of collective suffering for Israel becomes focused on the individual sufferer in Isaiah 52:13-53:12. There is no need here to defend a messianic interpretation, but simply to draw the connection between this One Who parallels the expected work of the promised Savior in Genesis 3:15. For example, we find in Isaiah 53:10 “But the LORD was pleased to crush Him, putting Him to grief; If He would render Himself as a guilt offering, He will see His offspring, He will prolong His days, and the good pleasure of the LORD will prosper in His hand.” It was God Who announced in His judgment that the Serpent would be used to crush the seed of the woman’s heel, but this would lead to his own head being crushed. This would only be possible if the seed of the woman survived the Serpent’s crushing to crush him in turn. Isaiah 53:10 reveals this fact as the suffering Servant dies and is resurrected (see verse 11, especially with the variant preserved in 1QIsaa and LXX, “light” [of new life]) as part of God’s purpose (i.e., His pleasure).

The Salvation Theme

Isaiah 53 likewise concerns a highly exalted, and hence royal, priestly figure (Isaiah 52:13, 15; cf. 6:1), who is referenced with the same pronoun הוא, hû’ (“he”) five times (53:4, 5, 7, 11, 12). Isaiah 53 (along with Zechariah 6) return us to the depiction of Adam as a priest-king and with Genesis 15:3-4 and 2 Samuel 7:12-14, link the promise of a seed in Genesis 3:15 even more strongly to an individual Messianic figure. It is this exalted figure Who will bring salvation through crushing his enemies. The LORD Himself will slay the serpent (Isaiah 27:1), put away sin (Micah 7:19; Psalm 103:12), and vanquish death (Isaiah 25:1; Hosea 13:14).

God’s promise to Abraham that “your seed shall possess the gate of their enemies” (Genesis 22:17) connects with the promise of the singular seed (heir) promised to Abraham in Genesis 15:4, since the Hebrew verb for "to be an heir" can also mean to "possess" as in this verse and in Genesis 24:60: “your descendants possess the gate of those who hate them.” In Isaiah 65:9 God promises a "seed" from Jacob related to the coming of a "possessor" from Judah (see Genesis 49:8-12; Num 24:17) and the nations are promised to one day become the Messiah's "inheritance" and the ends of the earth his "possession" (Psalm 2:8). Finally, Psalm 110:1 promises that Messiah’s enemies would become His footstool. Therefore we can see that the Pentateuch and other Old Testament passages link the seed of the woman in Genesis 3:15 to a royal individual who will climactically defeat his enemies, end the enmity, and inherit all that is promised in the Abrahamic covenant when he fully reigns.

The common theme of salvation (deliverance, vindication) from suffering (affliction, persecution) caused by enemies (adversaries) is accomplished by the crushing of the enemy, often the head. Depictions of enemy head-crushing go back to the First Egyptian Dynasty (King Narmer’s Cosmetic Palette, 31st century BC ) and symbolize the irreparable end of a foreign rule. Such foreign rule (over Israel) is the result of Satanic enmity. This we read: “God brings him out of Egypt, He is for him like the horns of the wild ox. “You crush the heads of Leviathan; You give him as food for the creatures of the wilderness.” (Psalm 74:14), “You crushed Rahab like one who is slain; You scattered Your enemies with Your mighty arm.” (Psalm 89:10), “But I shall crush his adversaries before him, and strike those who hate him.” (Psalm 89:23). These images of false pagan powers that symbolize the Serpent, are crushed as predicted in Genesis 3:15.his can also be seen in the messianic text of Numbers 24:8-17: “He shall devour the nations who are his adversaries, and shall crush their bones in pieces, and shatter them with his arrows” (verse 8). Verse 17 makes the connection of this imagery with Genesis 3:15: “I see him, but not now; I behold him, but not near; a star shall come forth from Jacob, and a scepter shall rise from Israel, and shall crush through the forehead of Moab, and tear down all the sons of Sheth.” The linkage here to Genesis 3;15 is the enmity of Moab (and in this context Edom) who are part of the serpent and his seed. This is also seen in the depiction of the messianic advent in Daniel 2:40, 44: “Then there will be a fourth kingdom as strong as iron; inasmuch as iron crushes and shatters all things, so, like iron that breaks in pieces, it will crush and break all these in pieces (cf. 7:23) And in the days of those kings the God of heaven will set up a kingdom which will never be destroyed, and that kingdom will not be left for another people; it will crush and put an end to all these kingdoms, but it will itself endure forever.” This end of the power and authority of the Serpent over the woman’s collective seed by the individual seed of the woman is the fulfillment of the salvation promised in Genesis 3:15.

Old Testament texts that develop the messianic themes of Genesis 3:15

- The New Testament Supports a Messianic Interpretation.

How does the New Testament interpret the Old Testament? Some have come to the conclusion that the authors of the New Testament wrongly interpreted the Old Testament and so are mystified as to how the authors of the New Testament claim there are references to the Messiah in Old Testament texts when these texts do not actually refer to Him. Others talk in terms of patterns and trajectories, reconstructing in their minds after a walk through the intertestamental period, how it could have been construed by Jesus and taught to His disciples, but no other mortal since could reproduce this mystery of inspiration. However, if we adopt the hypothesis that the Old Testament is a messianic document, written from a messianic perspective, to sustain a messianic hope, we might find that the interpretive methods employed by the authors of the New Testament are legitimate hermeneutical action that can be followed today. If the books of the Bible were written by and for a Remnant anticipating the coming of the Savior revealed in Genesis 3:15, we would expect to find in the text resonations of this promise of God. As Hamilton states “We do, in fact, find imagery from Gen 3:15 in many texts across both testaments. We have seen the seed of the woman crushing the head(s) of the seed of the serpent, we have seen shattered enemies, trampled enemies, dust eating defeated enemies, and smashed serpents. I find this evidence compelling. Hopefully others will as well, even if they do not entirely agree with the thesis that the OT is, through and through, a messianic document.”[32]

Since the Old Testament was the Bible of the Apostles and the early Church, the references we find to a satanic conflict and deliverance from it must have had a source text. For example, Acts 26:18 is a prayer “to open their eyes so that they may turn from darkness to light and from the dominion of Satan to God” and Hebrews 2:14 declares that “Since then the children share in flesh and blood, He Himself likewise also partook of the same, that through death He might render powerless him who had the power of death, that is, the devil.” This connection of an act of the devil that results in death and its final undoing by a divine-human “seed” has no real reference point in the Old Testament outside of Genesis 3:15. Likewise, 1 John 3:8, 10 states “the one who practices sin is of the devil; for the devil has sinned from the beginning. The Son of God appeared for this purpose, that He might destroy the works of the devil … By this the children of God and the children of the devil are obvious …” And John the Baptist and Jesus refer to the opposition Pharisees as "offspring of vipers" (Mt 3:7; 12:34; 23:33; Lk 3:7).[33] How else do we understand this explicit language and a dualism with its context in Eden and the proclamation of the divine Son to reverse this by the defeat of the devil without Genesis 3:15? And when Jesus declares that the devil is the father (source) of those who want to murder Him (John 8:44), does this not relate to the seed of the Serpent whose practice is enmity and whose intention is the crushing of the heel?

The text of Romans 16:20: “the God of peace will soon crush Satan under your feet,” which appears to find finds its reference in Genesis 3:15b, is said to argue against such a connection. It is clear this is not a citation from Genesis 3:15 since both the MT and LXX do not match Paul’s wording and because here it is the collective sense (ὑπο τοὺς πόδας ὑμῶν, ‘under your [pl.] feet’) God will soon crush (συντρίψει) Satan. However, it is God (singular) Who does the crushing here for the believers, exactly as predicted in Genesis 3:15b. While this is not a citation, it should not be doubted that Paul is alluding to this final victory, long promised, which will include all the righteous seed who have suffered under the satanic conflict. This accords with Romans 8:19-22 in which the cursed Creation will be set free through the final redemption of Christ, the seed of the woman. The full explanation of this victory is found in Revelation 12:9; 20:2, 10, where we read: “And the great dragon was thrown down, the serpent of old who is called the devil and Satan, who deceives the whole world … And he laid hold of the dragon, the serpent of old, who is the devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years, and the devil who deceived them was thrown into the lake of fire and brimstone, where the beast and the false prophet are also; and they will be tormented day and night forever and ever.” Only Genesis 3:15 can be in view as the serpent of old (i.e., “from the beginning,” 1 John 3:8), called the devil and Satan, is linked with deception and punished. As we near a conclusion, let us consider how Genesis 3:15 contributes to biblical theology and thereby adds support for a messianic interpretation.

- Biblical Theology Supports a Messianic Interpretation.

We have seen revealed in the grammar and literary themes of Genesis 3:15 a theological intentionality. God’s first act of judgment in the Bible is accompanied by his first promise of salvation, and the salvation will come through the judgment. Here I would like to mention only a few theological points that depend on Genesis 3:15 for their interpretation.

It is important to note here that Genesis 3:15 is addressed to “the serpent.” If this statement of on-going conflict were made to a mere reptile it would make no sense; it only has meaning if the recipient is sentient and in some way a participant in the future. It is not the serpent’s “seed” who will act to crush and be crushed, but “the serpent” himself. This is signified by the use of the personal pronoun in addressing the serpent, a clue that theologians have rightly discerned makes the serpent a vessel for a greater power, who the New Testament confirms as “the serpent of old who is called the devil and Satan” (Revelation 12:19; 20:2). The use of איבה (‘evah) from the root איב (‘ev) “be an enemy to, be at enmity with” envisions the world of mankind, especially those whose lives will relate to the woman’s “seed” (National Israel as the Chosen People and those who belong to the Messiah) as a war zone, a truth seen in the description of the fallen world as “under the power of the evil one” (1 John 5:19) and Satanic attacks against believers in the Old Testament (Job 1:6-12; 2:1-6), Israel (Deuteronomy 32:16-17; 1 Chronicles 21:1; Zechariah 3:1) and the believers in the Church Age (Acts 26:18; Ephesians 6:10-12; 1 Peter 5:8). The respective seed of the woman and of the serpent each appears to point to a certain kind of people: those who will in faith look for the promise-plan of God to bring salvation through the Messiah and those who in unbelief will oppose it.[34] These are later described as those whose “father is the Devil” (τοῦ πατρὸς τοῦ διαβόλου; John 8:44) and a “generation of vipers” (γεννήματα ἐχιδνῶν; Matthew 3:7; 12:34; 23:33; cf. Luke 3:7)[35] and those who are God’s chosen Remnant (בָּחַ֣ר; Genesis 18:19; Deuteronomy 14:2). This text affirms also that there is no eternal dualism between good and evil, for from the announcement of the conflict it has been certain that the good (the seed of the woman”) would prevail over evil (the Serpent and his seed).

I think that 1 Timothy 2:15 promises a type of future “salvation” (σωθήσεται) for the woman who is restricted in exercising leadership because of Eve (as a Federal Head) being deceived and usurping authority. If the woman raises children she will have her leadership fulfilled in and through them and if they remain godly children she will experience in their company and conduct a partial deliverance from the effects of life in a fallen world. This connection of with women under the curse with a “seed” that saves has a distinct echo of the promise of Genesis 3:15.

Finally, Genesis 3:15 provides the theological basis for identifying the Messiah in the Old Testament. As Tom Meyer has observed, “There has been only one descendent of Eve who conquered the old serpent (Revelation 12:9), who came to destroy his works (1 John 3:8), who was made of a woman (Galatians 4:4), without the help of man (Isaiah 7:14), and would bruise the serpent under his feet shortly (Romans 16:20); the last Adam (1 Corinthians 15:45), the Lord Jesus Christ.”[36]

Conclusion

Although recent scholarship has rejected the messianic interpretation of Genesis 3:15 in favor of an etiological or symbolic (allegorical) explanation, this paper has argued that the messianic interpretation contends that the author of the Torah offered a hint of a coming redeemer in Genesis 3:15 and then used the rest of the Pentateuch to identify Him as the future Messiah. Later Old Testament writers also recognized the seed as the future deliverer and referred to Genesis 3:15 as a messianic text. Though the text in Genesis does not explicitly identify the serpent as the devil nor the individual seed of the woman as Messiah the intertextual connections throughout the Old Testament develop these figures and confirm that the identifications made of them as Satan and Christ the New Testament were firmly founded. Genesis 3:15 is a direct Messianic prophecy and the first one in the Bible, programmatically setting the narrative storyline and focus for the rest of the Old Testament. As Chen, observes, “rightly appreciated, its dense, highly concentrated Messianic content shows where the Pentateuch's center of gravity lies. Salvation will come through the seed of the woman, not through the Sinai/Deuteronomic law which will be given later.”[37]

If Genesis 3:15 is the Proto-evangelium, then from start to finish, the Old Testament is a messianic document, written from a messianic perspective, to sustain a messianic hope. Later authors are not imposing a messianic interpretation on these texts but rightly interpreting them which explains why the New Testament views the Old Testament in its entirety as pointing to and being fulfilled in the one it presents as the Messiah (Luke 24:27, 44–45; cf. Matthew 5:17 and John 5:46).

Follow-up Conclusion: The Importance of Genesis 3:15 to Old Testament Interpretation

What is at stake in our search for Messiah in the Old Testament? Let us get to the theological heart of the matter: If there is no messianic prophecy in the Old Testament, then the critics are correct - we have a different god in the Old Testament than in the New Testament. We see only a vengeful God who punishes mankind with exile and death and destroys the sinful world with a Flood, but no God who has a plan to save that sinful world. We see men sacrificing to this wrathful God to appease Him, but no sacrifice on His part to redeem us. Abraham is told his “faith is counted as righteousness” (Genesis 15:6), but what does this mean? Is it his faith itself that is righteous or faith in a God Who has revealed He is just only because He is the Judge of all the earth (Genesis 18:25)? Is the Old Testament believer merely an enlightened Theist whose belief in a (even the) God is sufficient for salvation?[38] Moreover, we hear of His demand for human sacrifice and of His provision of a substitute on Mt. Moriah (Genesis 22) , but there is no prior revelation to link this to for understanding. We must wait until the New Testament where we are surprised by the unexpected demonstration of God’s love as a Savior and find Him in retrospect by re-reading the Old Testament with Christocentric glasses. Without messianic prophecy we may have a salvation at the sea (Exodus 15:1-2), but not a salvation from sin. Even the portrayal of Servant of the LORD (Isaiah 52:13-53:12) is someone else suffering for something else.

But, if from the outset of human sin and condemnation through the Fall we have God’s promise-plan revealed that the evil adversary who instigated the Fall and brought judgment will be conquered and the penalty of sin and death reversed by a divine-human seed, we from the beginning of the salvation story a God Who has a loving program of redemption that we can follow with faith through the years despite the judgment a Just God must visit upon His continuing sinning people. “In the short span of Gen 3:14–19, the God of the Bible is shown to be both just and merciful. The scene puts God on display as one who upholds righteousness and yet offers hope to guilty human rebels. He is a God of justice and so renders just condemnation for the transgressors. Yet he is also a God of mercy, and so he makes plain that his image bearers will triumph over the wicked snake.”[39] This is the revelation of a gracious God in the Old Testament Whose promise-plan progressively unfolds throughout Israel’s troubled history to produce a Remnant waiting for fulfillment by their long-expected Messiah. This is indeed what we find from the first chapter of the first book of the New Testament in the words “The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham,” and with Luke: “the son of Seth, the son of Adam, the son of God” (Luke 3:38). And so, we are not amazed by the depth of spiritual understanding in pagan King Herod when he asks his scribes for the birthplace of “the Messiah,” who he has recognized as the divinely promised “King of the Jews” (Matthew 2:4). Therefore, when we come to Genesis 3:15, we are faced with either finding a vengeful Deity Who exiles His cursed Creation with no clear promise of reversing the curse or restoring the Creation, or a gracious God Who promises a Savior to defeat the devil and redeem His Creation. Which interpretation of Genesis 3:15 do you think best explains the Promise-Plan of God revealed in the Old Testament?

[1] Satan is the animating force (cf. Revelation 12:9; 20:2) behind the Serpent and this is implied in the text by the Serpent’s traits: apparent autonomy, claim to superior knowledge of the Deity and blasphemous speech, all descriptions of other figures similarly possessed and used by the Evil One (the Kings of Babylon and Tyre and the Antichrist, Isaiah 14:13-14; Ezekiel 28:13a; Daniel 11:36; Revelation 13:2-6).

[2] James Scott, “Historical Development of the Messianic Idea,” The Old Testament Student 7:6 (1888), 176.

[3] For a discussion of this view and its advocates see Michael Rydelnik, The Messianic Hope: Is the Hebrew Bible Really Messianic? (Nashville: B&H, 2010), 131-34.

[4] Herbert W. Bateman IV, Darrell L. Bock, Gordon H. Johnston, Jesus the Messiah: Tracing the Promises, Expectations, and the Coming of Israel’s King (Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic, 2012), 459

[5] Ibid.

[6] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17, NICOT (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1995), 51.

[7] W. Hall Harris, ed., The NET Bible Notes, 1st Accordance electronic edition, version 4.1. Richardson: Biblical Studies Press, 2005. The revised Thomas Nelson edition of the NET Bible (2019) did not retain this comment in its notes and included an argument for a messianic interpretation.

[8] See for example R.A. Martin, ‘The earliest Messianic interpretation of Genesis 3:15’, Journal of Biblical Literature 84 (1965), 425-27, at 425: ‘The use of the masculine pronoun [he] in English is indefensible as a translation of the Hebrew… Grammatically [zera‘] is masculine, but actually it is a collective noun of which the natural gender is neuter. The proper translation in English of [hû’] would be either “it” or “they” (meaning “the descendants of Eve”).’

[9] Claus Westermann, Genesis 1-11, A Continental Commentary (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1994), 260 declares that Genesis 3:15 cannot be the Protoevangelium because “it is beyond doubt that zera’ is to be understood collectively.”

[10] Kevin Chen, The Messianic Vision of the Pentateuch (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2019), 43. Chen reports that in his research for this chart, every passage with seed and an independent personal pronoun within a o0ne-verse radius was collected, sifted for false positives, and analyzed.

[11] Kevin Chen, The Messianic Vision of the Pentateuch (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2019), 41, n. 12

[12] Jack Collins, “A Syntactical Note (Genesis 3:15): Is the Woman’s Seed Singular or Plural?” Tyndale Bulletin 48.1 (1997) 145.

[13] Seth Postell, “Genesis 3:15: The Promised Seed” in The Moody Handbook of Messianic Prophecy: Studies and Expositions of the Messiah in the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 2019), 241. See also Sailhamer, J.H., 1992, The Pentateuch as Narrative: A Biblical-Theological Commentary (Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI, 1992): 107–108.

[14] S. Kempf, “Genesis 3:14-19: Climax of the discourse?,” Journal of Translation and Textlinguistics

6 (1993), 354-77.

[15] Stephen Kempf, “Genesis 3:14-19: Climax of the Discourse?” Journal of Translation and Text Linguistics 6:4 (1993): 354-77.

[16] John H. Sailhamer, Genesis, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, rev. ed. Vol. 1, eds. T. Longman III and D. Garland (Grand Rapids: Zondervan , 2008), 91.

[17] T. Desmond Alexander and Gordon Wenham have pointed out the many parallels between the Garden of Eden and the Tabernacle, which include the LORD "walking about" in their midst (Gen 3:8; Lev 26:12), their entrance from the east and being guarded by cherubim (Gen 3:24; Ex 25:18-22; 26:1, 31; Num 3:38), the resemblance of the lampstand to the tree of life (Gen 2:9; 3:22; Ex 25:31-35), the presence of gold and onyx (Gen 2:11-12; Ex 25:7, 11, 17; 28:9), and the use of the same two Hebrew verbs (עבד, שמר) to describe Adam's tasks in the garden and the Levites' in the tabernacle (Gen 2:15; Num 3:7-8; 8:26). These extensive intertextual linkages within the Pentateuch itself cast the Garden of Eden as a prototypical sanctuary and Adam as a sort of prototypical Levite or priest. On this also see Randall Price, The Temple and Bible Prophecy: A Definitive Look at Its Past, Present, and Future 2nd edition (Eugene, OR: Harvest House Publishers, 2005), 187-206. See also the discussion with respect to Genesis 3:15 in Kevin Chen, The Messianic Vision of the Pentateuch (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2019), 37-38.

[18] I am indebted for this insight to Sandra L. Richter, The Epic of Eden: A Christian Entry into the Old Testament

(Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2008), 110.

[19] See “Onkelos Elucidated” and commentary notes in Targum Onkelos: The Definitive Aramaic Interpretive Translation of the Torah, Elucidated and Annotated (Artscroll Edition), Vol. 1 – Bereishis/Genesis (Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, Ltd, 2018), 31.

[20] Midrash Rabbah, Bereshit 22:2.

[21] J.T. Mueller, Martin Luther’s Commentary on Genesis 1 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1958), 80.

[22] “Note T” on Genesis 4:1, NET Bible, Full Notes Edition (Thomas Nelson, 2019), 13.

[23] Bruce K. Waltke with Charles Yu, An Old Testament Theology: An Exegetical, Canonical and Thematic Approach (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2007), 62.

[24] הבל properly means “breath” (rendered as ἀτμίς/ἀτμός in the version of Aquila Symmachus and Theodotion), or “vapor,” and therefore designates what is lacking in substance, ephemeral, without any result (as when paired with “chase after wind” in Eccl. 1:14). Life in a fallen world is transitory (law of entropy) and thereby frustrating because man finite, subjected to inequities and is unable to achieve the end of what he desires to know and to do (Eccl. 3:12-15). הבל was translated as “vanity” in the LXX (ματαιότης) and Vulgate (vanitas).

[25] Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., The Messiah in the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1995), 42.

[26] Seth Postell, “Genesis 3:15: The Promised,” The Moody Handbook of Messianic Prophecy (Chicago: Moody Press, 2019), 245.

[27] “The Messiah and the Hebrew Bible,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 44 [2001]: 23.

[28] #3 in “Our Desire to honor traditional Christian translation practices,” sv. “TLV Guidelines to view our ‘Hebraic Lens’,” Tree of Life Version of the Scriptures, First Edition (Snelville, GA: Messianic Jewish Family Bible Society, 2013).

[29] Adapted from chart in John H. Sailhamer, Genesis, Expositor’s Bible Commentary. Revised ed. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), 133

[30] Kevin Chen, The Messianic Vision of the Pentateuch (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2019), 45.

[31] David Dorsey, The Literary Structure of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2004).

[32] James Hamilton, The Skull Crushing Seed of the Woman: Inner-Biblical Interpretation of Genesis 3:15,” The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology (June 21, 2006), 43.

[33] Chen, The Messianic Vision of the Pentateuch, 40-41.

[34] See further, Waltke, B.K. & Fredricks, C.J., Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI, Zondervan, 2001): 93–94

[35] For a fuller development of this idea in relation to the text of Genesis 3:15 see Philip La Grange du Toit, “‘This Generation’ in Matthew 24:34 as a Timeless, Spiritual Generation Akin to Genesis 3:15,” Verbum et Ecclesia 39(1) 2018, a1850. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve. v39i1.1850.

[36] Tom Meyer, The Book of Genesis: A Verse by Verse Commentary (Columbia, SC: Create Space, 2018), 18.

[37] Chen, The Messianic Vision of the Pentateuch, 66.

[38] This is the question posed by Walter C. Kaiser, Jr. in “Is it the Case that Christ is the Same Object of Faith in the Old Testament? (Genesis 15:1–6),” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 55/2 (2012) 291–98.

[39] James Hamilton, The Skull Crushing Seed of the Woman: Inner-Biblical Interpretation of Genesis 3:15,” The Southern Baptist Journal of Theology (June 21, 2006), 31.