John 14:1-3-The Father's House: Are We There Yet?

Mr. George Gunn

Shasta Bible College

In My Father's house are many dwelling places; if it were not so, I would have told you; for I go to prepare a place for you. If I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and receive you to Myself, that where I am, there you may be also.

John 14:2-3

Abstract: The promise in Jn 14:2-3 that Jesus will come again has been taken by many Christians as a promise of Christ's parousia. Seen in this way, the promise is of significant importance to the pretribulational rapture position. Many non-dispensational scholars, however, have sought to present this promise as non-eschatological and, thus, not a promise of the rapture. Their arguments are based both on their understanding of the context of the Upper Room Discourse and on the specific language used by Jesus in these verses. After demonstrating the importance of this promise to the pretribulational rapture position, I will defend its eschatological interpretation by examining the history of its interpretation, the context of the saying, and the specific language employed by Jesus.

Introduction: Importance of John 14:1-3 to the Pretrib Position

I. Various Interpretations of John 14:1-3

II. History of the Interpretation of John 14:1-3

- Papias (ca. 110)

- Irenaeus (ca. 130-202)

- Tertullian (ca. 196-212)

- Origen (ca. 182-251)

- Cyprian (d. 258)

III. Exegesis of John 14:1-3

- Context

- Verse 2

- Verse 3

Conclusions and Implications

Introduction: Importance of John 14:1-3 to the Pretrib Position

The rapture, though alluded to frequently in the New Testament, is really only described in detail in 3 passages: John 14:1-3; 1 Corinthians 15:51-54; and 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18. One could possibly add Philippians 3:20-21, but the reference is less specific there. Each of these passages contributes information about the event, and, taken together, we have a fairly complete description of the event. However, the information from all 3 passages is required in order to piece together a complete picture of the rapture. The event takes place in five distinct movements:

- The Lord Jesus, along with the spirits of those believers who have died during the church age, descends from heaven to earth's atmosphere.

- The bodies of believers who have died during the church age are resurrected.

- Believers who are alive at the time of the rapture are changed to receive glorified bodies.

- Together, resurrected bodies of dead saints and changed living believers are caught up to the Lord in the atmosphere.

- The assembled company of all believers from the entire church age, along with the Lord, accompanies the Lord on His journey from the atmosphere to His next venue.

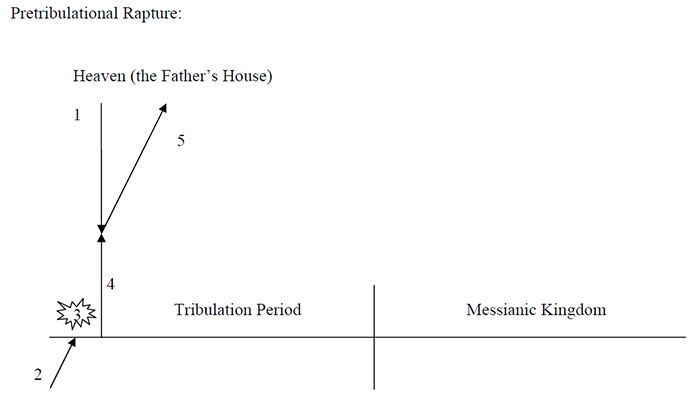

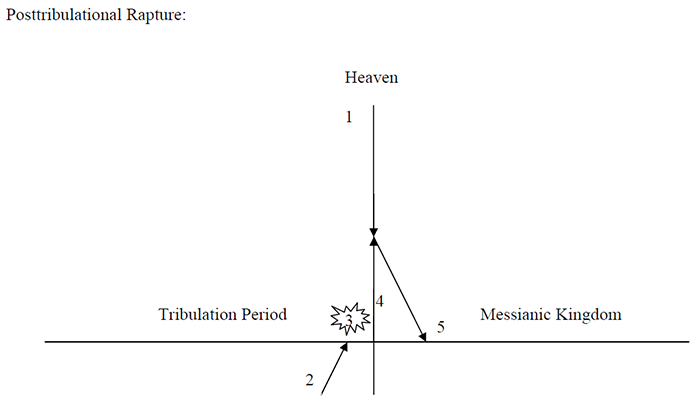

You'll notice that I have worded the fifth movement in such a way that it could fit the description of either a pretribulational rapture, posttribulational rapture, or other rapture-timing option relative to the tribulation. Essentially, anyone who actually believes in a rapture could agree with this five-movement description. What really divides the pretribulational position from the posttribulational position is the question of the “next venue” for the Lord following the rapture. The two positions, with their five movements, can be presented diagrammatically as follows:

Thus, though we often think of the difference between the pretribulational position and the posttribulational position as being one of timing, it might also be conceived as a difference in venue. Posttribulationist Robert Gundry recognized the importance of venue to the pretribulation position when he stated, “...no passage concerning the rapture incorporates a return to heaven.”[1] As we shall see, to support his position, Gundry reinterprets John 14:1-3 so as to make it a non-eschatological promise. It is because of this issue of venue that John 14:1-3 is so crucial to the pretribulational position. I must disagree with E. Schuyler English when he says that, “...while the promise of John 14:3 is the first New Testament intimation of the Rapture, it cannot be said to be descriptive of it.”[2] Indeed, as we shall see, John 14:1-3 contains specific, detailed and vital information descriptive of the rapture. The importance of John 14:1-3 for the pretribulation position is further seen in a recent statement by Lutheran theologian Barbara Rossing:

“I call it [dispensationalism] a theological racket,” says Barbara Rossing, an edge in her voice. The Lutheran theologian has little patience for dispensationalism. The basis cited for its concept of the Rapture is just as summarily dealt with. “If you look closely at that passage [1 Thess 4:13-18], Jesus is descending from heaven,” Rossing says. “Yes, to be sure, Paul says people will be snatched up in the air to meet Jesus, but it never says that Jesus turns around, switches direction and goes back up to heaven for seven years. They have to insert that. They have to make that up because it's not in the text.”[3]

Rossing, of course, was restricting her comments solely to 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18, as if that were the only passage dealing with the rapture. If that were the only passage describing the rapture, she would be correct. In fact, with the exception of John 14, no major rapture passage (1 Cor 15:51-54; Phil 3:20-21; 1 Thess 4:13-18) explicitly mentions the return to heaven.[4] Only John 14 specifically describes the return to heaven as the final venue of the rapture event.

Those who hold to a pretribulational rapture tend to agree that John 14:1-3 describes the rapture. Those who do not hold to the pretribulational position generally fall into two broad categories: (1) John 14:1-3 describes the rapture but it is not pretribulational (i.e., it is either posttribulational or coincident with either an amillennial or postmillennial parousia), and (2) John 14:1-3 describes a non-eschatological coming of Christ (i.e. post-resurrection, post-ascension, or some other “coming” event). If the promise of John 14:1-3 can be shown to be an eschatological coming, I believe the issue of venue forces us to the pretribulational position. The most crucial issues, then, that must be settled are:

- Is the promise eschatological or non-eschatological?[5]

- What venue is described by the “Father's house,” “mansions,” and the “place prepared” by Jesus.

Therefore, it is with this reminder of the importance of John 14:1-3 for the pretribulational position, that we focus our attention on this fascinating passage of Scripture.

I. Various Interpretations of John 14:1-3

When it comes to John 14:1-3, the challenge confronting the interpreter of Scripture is daunting. In the short span of three verses, differing views by major commentators on the meaning of four different expressions yield no less than seventeen different interpretations! Following is a brief survey of these interpretations:

● Believe ... believe (πιστεύετε ... πιστεύετε, pisteuete ... pisteuete), verse 1

The verb occurs twice in this verse, the form being identical for both. Both occurrences could be either indicative or imperative. This gives the possibility of four different interpretations. Though the differences are noted by most commentaries, they have little bearing on the actual meaning of this verse, at least as it pertains to our discussion of the rapture.

1. Two Indicatives. “You believe in God; you also believe in me.”

2. Indicative Followed by Imperative. “You believe in God; believe also in me.”

3. Imperative Followed by Indicative. “Believe in God; indeed, you believe in me.”

4. Two Imperatives. “Believe in God; believe also in me.”

● My Father's House (τῇ οἰκίᾳ τοῦ πατρός μου, tei oikia tou patros mou), verse 2

This precise phrase does not occur elsewhere in John, though a very similar one occurs one other time in John, where it is a reference to the temple in Jerusalem (2:16). Luke 2:49 is perhaps a similar reference to the temple, but it lacks the word “house” (either οἴκος, oikos or οἰκία oikia). Luke 16:27 and Acts 7:20, the only other similar NT references, refer to earthly houses of human fathers. This has given rise to at least three interpretations for the phrase in John 14:2.

5. Heaven.

“Jesus was leaving to prepare a place for them in heaven, the Father's house.[6]

“My Father's house” clearly refers to heaven.”[7]

6. Both Heaven and Earth.

“Very attractive is the view ... that 'my Father's house' includes earth as well as heaven, so that wherever we are we are in that house.”[8]

7. The Body of Christ As The New Temple.

“The same expression, 'Father's house,' appears in 2:16, in which it is clear that the temple in Jerusalem was the Father's house. Yet in the next few verses (2:17-21) Jesus likened himself to a temple, a temple that would be destroyed and raised again in three days. The Son, through the process of crucifixion and resurrection, would become the temple, the Father's house, prepared to receive the believers. He, as the temple, the Father's house, would be the means through which the believers could come to dwell in the Father and the Father in them.”[9]

● Dwelling Places (μοναὶ, monai), verse 2

This noun occurs only one other time in all the New Testament (John 14:23) where it is a reference to Jesus and the Father's coming to make their dwelling with the believer during the church age. Two interpretations have been given for this.

8. Dwelling Places in Heaven.

“The phrase ['many mansions'] means that there is room to spare for all the redeemed in heaven”[10]

9. The Believer As God's Dwelling Place

“John presumably means this language figuratively for being in Christ, where God's presence dwells (2:21); the only other place in the New Testament where this term for “dwelling places” or “rooms” occurs is in 14:23, where it refers to the believer as God's dwelling place (cf. also the verb “dwell”—15:4–7).”[11]

● I will come again (πάλιν ἔρχομαι, palin erchomai), verse 3

Many of the preceding interpretive choices ultimately depend on, or determine, how one interprets this phrase. Because the verb occurs in the present tense, some have been reluctant to take this as predictive of a future event. Others, while admitting that the present is “predictive” are unwilling to make it predictive of a distant future event.

“The Greek here is in the present tense and should properly be translated 'I am coming,' showing the immediacy of the Lord's return. His coming to them again would be realized in a short while.”[12]

Thus, at least eight different interpretations have been posited: [13]

10. Christ's Return From Death at The Resurrection and the Post-Resurrection Appearances.

“... the going away and coming again, according to the context of John 14-16, would be but for 'a little while' (see 14:19-20; 16:16-23), not two or more millennia! Indeed 14:20 and 16:20-22 make it evident that 'that day' would be the day of Christ's resurrection, the day in which the disciples would realize that they had become united to the risen Christ.... When Jesus said, 'I am coming again,' that 'coming again' occurred on the day of his resurrection (see Dodds).”[14]

11. Christ's Coming on the Day of Pentecost in the Person of the Holy Spirit to Bring Believers into the Body of Christ.

“In this context, John probably means not the Second Coming but Christ's return after the resurrection to bestow the Spirit (14:16–18). In Jewish teaching, both the resurrection of the dead (which Jesus inaugurated) and bestowal of the Spirit indicate the arrival of the new age of the kingdom.”[15]

“This coming refers, therefore, ... to the return of Jesus through the Holy Spirit, to the close and indissoluble union formed thereby between the disciple and the glorified person of Jesus; comp. all that follows in vv. 17, 19-21, 23; especially ver. 18, which is the explanation of our: I come again.”[16]

12. Christ's Coming to the Believer at Death to Receive Him to Heaven.

“This verse is much used by pre-tribulationists to support the theory that when Christ returns it will be not to establish His earthly kingdom, but to take His disciples from earth to heaven seven years before the kingdom. John 14:3, however, is 'variously interpreted'; and the very doubtfulness of its application has caused some recent defenders of the dispensationalist viewpoint deliberately to omit it from their argument. The interpretation that seems the most plausible contextually is that at a believer's death, 'I come and will receive you unto myself' in glory... The immediate context suggests nothing about the visible second advent but rather uses 'I come' in a spiritual sense (v. 18).”[17]

13. Christ's Coming for the Church at the Pretribulational Rapture.

“I will come back refers here, not to the Resurrection or to a believer's death, but to the Rapture of the church when Christ will return for His sheep (cf. 1 Thes. 4:13-18) and they will be with Him (cf. John 17:24).”[18]

14. Christ's Coming in Power and Glory at the Posttribulational Parousia.

“Furthermore, only two days following the Olivet Discourse, Jesus talked about the [posttribulational] rapture in the Upper Room (John 14:1-3).”[19]

15. Christ's Coming at the Last Great Judgment.

“This return must not be understood as referring to the Holy Spirit, as if Christ had manifested to the disciples some new presence of himself by the Spirit. It is unquestionably true, that Christ dwells with us and in us by his Spirit; but here he speaks of the last day of judgment, when he will, at length, come to assemble his followers.”[20]

16. Christ's Coming to the Believer at Individual Salvation.[21]

17. Christ's Ever Coming into the World and to the Church as the Risen Lord.

“But though the words refer to the last 'coming' of Christ, the promise must not be limited to that one 'coming' which is the consummation of all 'comings.' Nor again must it be confined to the 'coming' to the Church on the day of Pentecost, or to the 'coming' to the individual either at conversion or at death, though these 'comings' are included in the thought. Christ is in fact from the moment of His Resurrection ever coming to the world and to the Church, and to men as the Risen Lord (comp. 1:9).”[22]

II. History of the Interpretation of John 14:1-3

Everyone likes to appeal to the early church fathers when their views are in agreement with them! As pretribulation rapturists, we have not had the most pleasant experience in this realm of exegesis. Due to the lack of corroboration for a pretribulational rapture from the early church fathers, some have cast aspersion on our view of the rapture. In reply, we have argued that patristic interpretation is not necessarily a sure guide to correct theology. The early fathers were clearly wrong on a number of issues (e.g. baptismal regeneration, allegorical hermeneutics, the value of asceticism, etc.).[23] Nevertheless, they were also right on a number of issues, due to the fact that oral transmission of traditional interpretation was still only a generation or two removed from the apostles. At the very least, it would be interesting to see whether the early Christian writers understood John 14:1-3 as being eschatological and the “Father's house” as a reference to heaven. If the apostles had understood the reference to be both eschatological and heavenly, then we would expect the early fathers to reflect this understanding. In fact, we do find that the extant writings of the early fathers viewed this passage as having an eschatological orientation and the “Father's house” as a reference to heaven. At least five ante-nicene fathers make reference to John 14:1-3 in their writings.

1. Papias (ca. 110) – Exposition of the Oracles of the Lord, IV, Preserved in Irenaeus Against Heresies who makes mention of these fragments of Papias as the only works written by him, in the following words: “Now testimony is borne to these things in writing by Papias, an ancient man, who was a hearer of John, and a friend of Polycarp, in the fourth of his books; for five books were composed by him.” Papias understood the promise of John 14:1-3 as an eschatological coming to take believers to heaven in conjunction with their judgment of rewards:

“As the presbyters say, then those who are deemed worthy of an abode in heaven shall go there, others shall enjoy the delights of Paradise, and others shall possess the splendor of the city; for everywhere the Savior will be seen, according as they shall be worthy who see Him. But that there is this distinction between the habitation of those who produce an hundredfold, and that of those who produce sixty-fold, and that of those who produce thirty-fold; for the first will be taken up into the heavens, the second class will dwell in Paradise, and the last will inhabit the city; and that on this account the Lord said, 'In my Father's house are many mansions:' for all things belong to God, who supplies all with a suitable dwelling-place, even as His word says, that a share is given to all by the Father, according as each one is or shall be worthy. And this is the couch in which they shall recline who feast, being invited to the wedding.”

2. Irenaeus (ca. 130-202) – Against Heresies, Book III, Ch. XIX.3 – Irenaeus describes the future day of the Christian's resurrection as a day when the believer will be caught up to the mansions in the Father's house in heaven:

“Wherefore also the Lord Himself gave us a sign, in the depth below, and in the height above, which man did not ask for, because he never expected that a virgin could conceive, or that it was possible that one remaining a virgin could bring forth a son, and that what was thus born should be 'God with us,' and descend to those things which are of the earth beneath, seeking the sheep which had perished, which was indeed His own peculiar handiwork, and ascend to the height above, offering and commending to His Father that human nature (hominem) which had been found, making in His own person the first-fruits of the resurrection of man; that, as the Head rose from the dead, so also the remaining part of the body–[namely, the body] of every man who is found in life–when the time is fulfilled of that condemnation which existed by reason of disobedience, may arise, blended together and strengthened through means of joints and bands by the increase of God, each of the members having its own proper and fit position in the body. For there are many mansions in the Father's house, inasmuch as there are also many members in the body.”

3. Tertullian (ca. 196-212)

a. On the Resurrection of the Flesh, XLI – Tertullian sees in John 14:1-3 an eschatological coming at the time of the resurrection to take believers to heaven.

“'For we know;' he [Paul] says, 'that if our earthly house of this tabernacle were dissolved, we have a house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens;' in other words, owing to the fact that our flesh is undergoing dissolution through its sufferings, we shall be provided with a home in heaven. He remembered the award (which the Lord assigns) in the Gospel: 'Blessed are they who are persecuted for righteousness' sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.' Yet, when he thus contrasted the recompense of the reward, he did not deny the flesh's restoration; since the recompense is due to the same substance to which the dissolution is attributed, - that is, of course, the flesh. Because, however, he had called the flesh a house, he wished elegantly to use the same term in his comparison of the ultimate reward; promising to the very house, which undergoes dissolution through suffering, a better house through the resurrection. Just as the Lord also promises us many mansions as of a house in His Father's home.”

b. Scorpiace, Antidote for the Scorpion's Sting, Ch. VI – In a passage describing the rewards that await the Christian martyr, Tertullian likens the martyr to an athlete who endures pain and suffering in order to win the prize. The awarding of that prize takes place in the future in the Father's house:

“Suits for injuries lie outside the racecourse. But to the extent that those persons deal in discoloration, and gore, and swellings, he will design for them crowns, doubtless, and glory, and a present, political privileges, contributions by the citizens, images, statues, and–of such sort as the world can give–an eternity of fame, a resurrection by being kept in remembrance. The pugilist himself does not complain of feeling pain, for he wishes it; the crown closes the wounds, the palm hides the blood: he is excited more by victory than by injury. Will you count this man hurt whom you see happy? But not even the vanquished himself will reproach the superintendent of the contest for his misfortune. Shall it be unbecoming in God to bring forth kinds of skill and rules of His own into public view, into this open ground of the world, to be seen by men, and angels, and all powers? – to test flesh and spirit as to steadfastness and endurance? – to give to this one the palm, to this one distinction, to that one the privilege of citizenship, to that one pay? – to reject some also, and after punishing to remove them with disgrace? You dictate to God, forsooth, the times, or the ways, or the places in which to institute a trial concerning His own troop (of competitors) as if it were not proper for the Judge to pronounce the preliminary decision also. Well now, if He had put forth faith to suffer martyrdoms not for the contest's sake, but for its own benefit, ought it not to have had some store of hope, for the increase of which it might restrain desire of its own, and check its wish in order that it might strive to mount up, seeing they also who discharge earthly functions are eager for promotion? Or how will there be many mansions in our Father's house, if not to accord with a diversity of deserts?”

c. On Monogamy, Ch. X – In this passage the “many mansions” and the “house of the ... Father” are clearly references to heaven where we will one day receive our reward after our resurrection:

“But if we believe the resurrection of the dead, of course we shall be bound to them with whom we are destined to rise, to render an account the one of the other. But if in that age they will neither marry nor be given in marriage, but will be equal to angels, is not the fact that there will be no restitution of the conjugal relation a reason why we shall not be bound to our departed consorts? Nay, but the more shall we be bound (to them), because we are destined to a better estate–destined (as we are) to rise to a spiritual consortship, to recognize as well our own selves as them who are ours. Else how shall we sing thanks to God to eternity, if there shall remain in us no sense and memory of this debt; if we shall be reformed in substance, not in consciousness? Consequently, we who shall be with God shall be together; since we shall all be with the one God–albeit the wages be various, albeit there be 'many mansions', in the house of the same Father having labored for the 'one penny' of the self-same hire, that is, of eternal life; in which (eternal life) God will still less separate them whom He has conjoined, than in this lesser life He forbids them to be separated.”

4. Origen (ca. 182-251)

a. Commentary on the Gospel of John. Tenth Book. 28 – Though known for his allegorical interpretations, Origen did sometimes interpret literally. He appears to have done so here, interpreting the Father's house and the many mansions in terms of the eschatological feast in the kingdom of heaven:

“Now, those who believe in Him are those who walk in the straight and narrow way, which leads to life, and which is found by few. It may well be, however, that many of those who believe in His name will sit down with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven, the Father's house, in which are many mansions.”

b. De Principiis. Ch. XI On Counter Problems. 6 – Here, Origen's view of what becomes of the soul after death may seem a bit strange. Nevertheless, he clearly sees the “Father's house” as a reference to heaven and the “mansions” as other-worldly spheres leading to the Father's House.

“I think, therefore, that all the saints who depart from this life will remain in some place situated on the earth, which holy Scripture calls paradise, as in some place of instruction, and, so to speak, class-room or school of souls, in which they are to be instructed regarding all the things which they had seen on earth, and are to receive also some information respecting things that are to follow in the future, as even when in this life they had obtained in some degree indications of future events, although 'through a glass darkly,' all of which are revealed more clearly and distinctly to the saints in their proper time and place. If any one indeed be pure in heart, and holy in mind, and more practiced in perception, he will, by making more rapid progress, quickly ascend to a place in the air, and reach the kingdom of heaven, through those mansions, so to speak, in the various places which the Greeks have termed spheres, i.e., globes, but which holy Scripture has called heavens; in each of which he will first see clearly what is done there, and in the second place, will discover the reason why things are so done: and thus he will in order pass through all gradations, following Him who has passed into the heavens, Jesus the Son of God, who said, 'I will that where I am, these may be also.' And of this diversity of places He speaks, when He says, 'In My Father's house are many mansions.'”

5. Cyprian (d. 258) – Treatise II, On the Dress of Virgins. 23. Though we would probably disagree with Cyprian's view on celibacy, he nevertheless clearly viewed both the “Father's house” and the “mansions” as references to our future abode in heaven:

“The first decree commanded to increase and to multiply; the second enjoined continency. While the world is still rough and void, we are propagated by the fruitful begetting of numbers, and we increase to the enlargement of the human race. Now, when the world is filled and the earth supplied, they who can receive continency, living after the manner of eunuchs, are made eunuchs unto the kingdom. Nor does the Lord command this, but He exhorts it; nor does He impose the yoke of necessity, since the free choice of the will is left. But when He says that in His Father's house are many mansions, He points out the dwellings of the better habitation. Those better habitations you are seeking; cutting away the desires of the flesh, you obtain the reward of a greater grace in the heavenly home.”

So we see that, from the earliest years following the death of the apostle John, through the mid third century, the promise of John 14:1-3 was seen in terms of a future coming to receive believers to heaven. The ante-nicene fathers did not think that this promise had been fulfilled either in Christ's own resurrection or in the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. And since the promise was seen as something to be fulfilled in conjunction with the believer's bodily resurrection, they clearly were not thinking in terms of multiple comings being fulfilled at individual Christians' deaths, much less of a spiritual coming at the salvation of each individual Christian, but of a future day when all believers will be raised to receive their rewards.[24]

III. Exegesis of John 14:1-3

Context

Any discussion of the exegesis of a passage needs to pay close attention to the context. John 14:1-3 is no exception to this important hermeneutical principle. Those who argue for a non-eschatological interpretation of Jesus' promise are fond of pointing out that matters of eschatology are almost entirely missing from the Upper Room Discourse and are certainly to be found nowhere in the immediate context of our passage. It is universally acknowledged that John is the least eschatological of the 4 Gospels. In fact, as Tenney admitted, “I will come back” of verse 3 is “one of the few eschatological allusions in this Gospel.”[25] We should therefore raise the question of whether this promise is indeed an eschatological promise.

It is true that the Upper Room Discourse is not an eschatological discourse per se (like the Olivet Discourse or the parables of the Kingdom). However, to rule out the possibility of any eschatological reference on this basis is unwarranted. This is not the only place in the Gospel of John that an eschatological saying of Jesus occurs in the midst of a non-eschatological discourse. See, e.g., John 5:25-29; 6:39, 40, 44, 54.[26] A reference in the Upper Room Discourse to His coming back is entirely appropriate to a context that deals supremely with words of comfort given to the disciples He is about to leave. And while it is true that comfort is offered by means of reference to the coming of the Paraklete in John 16:7, this same Paraklete will “comfort” them in part by “showing them things to come” (16:13). Is it possible that Paul had these words of Christ in mind when he concluded his rapture passage with the statement: “Wherefore comfort one another with these words” (1 Thess 4:18)?[27]

Additionally, in a discussion of context we need to recognize that there are two distinct contexts to consider when interpreting this passage: (1) the context of the original saying; (2) the context of the recording of this saying some 60 or more years later. Borchert recognizes the significance of this distinction when he writes,

John once again is addressing the turmoil within his community of believers in a heart-to-heart manner. He does so at the same time as he portrayed Jesus addressing his disciples. Accordingly, we have another example of a double-level presentation reflecting two historical settings.[28]

Another way to think of this difference is to observe the distinction between what Sailhamer refers to as “text” and “event.”[29] In terms of the text, we recognize that this discourse was recorded by the apostle John somewhere in the mid to late 90s and was included in his gospel to help further his purpose of bringing unbelievers to faith in Jesus (John 20:30-31). On the other hand, when we consider the event itself, we have a different time frame, a different purpose, and thus a different context. We are not only looking here at inspired text recorded by the apostle John, we are also looking at the words of Jesus spoken to His disciples for the purpose of giving them the information they will need in order to live a faithful life in the days following His departure from them.[30] The difference may be presented diagrammatically as follows:

|

|

Event (The Original Saying by Jesus) |

Text (The Recording by John) |

|

• Time Frame - |

Early to mid 30s |

Mid to late 90s |

|

• Audience - |

Disciples |

Unbelievers |

|

• Purpose - |

Instruction for discipleship |

Evangelistic (John 20:31) |

|

• Context - |

Passover Meal and Last Supper |

Upper Room Discourse (John 13-16) |

Thus, we may consider the possibility that there was in fact an appropriate eschatological context in the original saying that did not suit John's evangelistic purpose. This being the case, John would simply have omitted those features that described the eschatological context. Jesus may have had a reason for speaking eschatologically to His disciples, but when John recorded these words for unbelievers, he meant to bring out the evangelistic application. But are we simply “grasping at straws” when we speak about some supposed eschatological context? Is there any actual evidence for such a theoretical context? I believe there is such evidence.

When we compare John's Gospel with the Synoptic Gospels we observe some very interesting features. John has the discourse, but the Synoptics do not. On the other hand, the Synoptics have The Lord's Supper, while John does not. However, we know by comparing certain events of the Upper Room Discourse with the Synoptic Gospel accounts of the Lord's Supper that they occurred at the same time. Edersheim notes: “... so far as we can judge, the Institution of the Holy Supper was followed by the Discourse recorded in St. John xiv.”[31] The Lord's Supper itself is an institution that is meaningful for the believer but not necessarily for the unbeliever, and thus was not relevant to John's evangelistic purpose. It seems reasonable, therefore, that John would omit a description of the institution of this ordinance. But it is specifically this “Last Supper context” that provides us with the eschatological setting for Jesus' promise. From the Synoptic Gospels, we find that the Supper was instituted with an accompanying eschatological reference when Jesus said, “I will not drink henceforth from this yield of the vine until that day when I drink it with you anew in my Father's kingdom” (Mt 26:29). Furthermore, when we note the progress of the Seder celebration and how it correlates with the discussions in the upper room we find an additional – and very significant – eschatological setting. Edersheim reconstructs the Last Supper and its correlation with the Upper Room Discourse as follows:[32]

|

Paschal Supper |

Upper Room Discourse |

|

|

|

Washing the Disciples' Feet (13:5-17) |

|

|

|

(Breaking “the bread” of the Eucharist – Mt 26:26; Mk 14:22; Lk 22:17; not in Jn) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prediction of Judas' Betrayal (13:18-30) Prediction of Jesus' Departure (13:31-35) Prediction of Peter's Denial (13:36-38) |

|

“The Cup of Blessing” (1 Cor 10:16) = the Communion Cup (Mt 26:27; Mk 14:23; Lk 22:20; not in Jn) |

|

|

|

Discourse of John 14 |

If Edersheim is correct in his reconstruction of the events of that night, then John 14 immediately follows the singing of the eschatological Psalm 118. With the refrain of “Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord” (Ps 118:26) still ringing in the disciples' ears, Jesus comforts their sorrowing hearts with this promise, “I come again to receive you to myself....” Yes, there is indeed an eschatological context, and the significance of the specific language of Psalm 118:26 will be explored below under the exegesis of verse 3.

Verse 2

“My Father's House”

Some non-eschatological approaches to this passage make note of the fact that this precise phrase occurs only one other time in the Gospel of John (2:16), and that there it is clearly a reference to the temple. Hence, they argue, this reference must be to the new temple, the church (as in Eph 2:20-22). For example, Craig Keener:

The “Father's house” would be the temple (2:16), where God would forever dwell with his people (Ezek 43:7, 9; 48:35; cf. Jn 8:35). The “dwelling places” (NASB, NRSV) could allude to the booths constructed for the Feast of Tabernacles but probably refer to “rooms” (cf. NIV, TEV) in the new temple, where only undefiled ministers would have a place (Ezek 44:9–16; cf. 48:11). John presumably means this language figuratively for being in Christ, where God's presence dwells (2:21); ... In this context, John probably means not the Second Coming but Christ's return after the resurrection to bestow the Spirit (14:16–18).[34]

If John 2:16 were the only other occurrence of the exact same phrase, Keener would have a point, but John in fact has not used precisely the same phrase in 14:2 as he did in 2:16. In fact he used a different, though cognate, term for the word “house.” John 2:16 uses the masculine noun οἴκος (oikos); whereas 14:2 uses the feminine οἰκία (oikia). Though generally considered as covering the same semantic range in the New Testament, these words originally were “differentiated in meaning.”[35] Now, only the apostle John himself could provide us with the exact reason why he used different words in the two verses, but sound exegesis at least inquires into any possible reason for the change of terms, and indeed should caution us against building too much significance on the parallel, when, in fact, different words have been used.

οἰκος (oikos) is the predominant term used in the NT,[36] but οἰκία (oikia) the predominant term in John (perhaps twice as often as οἰκος, oikos).[37] Thus, John's use of οἰκος (oikos) for the temple in 2:16 appears to be a conscious, definite selection of terminology. This might lead us to suspect that his use of οἰκία (oikia) in 14:2 is not a reference to cultic temple imagery, but rather to heaven as God's abode, i.e., His household as a place where He and His family members abide. As noted in TDNT:

In the NT, too, we find both οἶκος and οἰκία; the gen. τοῦ θεοῦ is usually linked with οἶκος, not οἰκία (though cf. Jn. 14:2: ἐν τῇ οἰκίᾳ τοῦ πατρός μου). As in the LXX, οἶκος τοῦ θεοῦ is used in honour of the earthly sanctuary of Israel. No other sacred or ecclesiastical structure is called by this term in the NT sphere. But the Christian community itself is the → ναὸς τοῦ θεοῦ, the οἶκος τοῦ θεοῦ (Hb. 3:6; 1 Pt. 4:17; 1 Tm. 3:15) and the οἶκος πνευματικός (1 Pt. 2:5). It may be supposed that this usage was common to primitive Christianity and became a permanent part of the preaching tradition... Jn. 14:2f ... This saying, which would seem to have lost its original form, is fairly isolated in the context, and is perhaps older than the sayings around it. ... the Father's dwelling has places of rest for the afflicted disciples of Jesus.[38]

It appears, then, that the masculine οἶκος in John 2:16 makes that verse an unsuitable parallel for the feminine οἰκία in 14:2. So, if we should not use John 2:16 as a parallel, how shall we proceed in determining the meaning of the phrase “my Father's house”? Well, it turns out that the expression “father's house” actually occurs quite frequently in Scripture, particularly in the OT, and was probably a recognizable phrase with a coherent semantic range of meaning for first century Jews. It is here that I believe we can find some help in determining the meaning of Jesus' use of the phrase in John 14:2. Many of these OT occurrences are irrelevant to our context – for example, those that refer to a “father's house” as one's clan or family extended over several generations. But of particular significance to its use in John 14 are the occurrences where someone either leaves or returns to his father's house. It should be noted that Jesus' coming from heaven and returning to heaven is a significant sub-theme of the Gospel of John (see below and in the appendix); thus, if the “Father's house” is a reference to heaven, then Jesus' language here can be seen within the context of this sub-theme.

The first of these OT occurrences that have to do with coming from or going to one's father's house is the command to Abraham to leave his father's house (Gen 12:1). Could there be a parallel between Jesus' use of the phrase “Father's house” and the covenantal command issued to Abraham? Some insight into a first-century understanding of the expression may come from the Apocalypse of Abraham:

The story of Apocalypse of Abraham begins with Abraham's conversion to the worship of the one God (Apoc. Abr. 1–8). While tending to his father's business as a carver of idols, Abraham perceives the helplessness of these human artifacts. Stone gods break; wooden gods burn; either may be sunk in the waters of a river or be smashed in a fall. Abraham realizes that rather than being gods to his father, Terah, the idols are his father's creatures. It is Terah who functions as a god in creating the idols. As Abraham ponders the helplessness of his father's idols, he hears the voice of the Mighty One coming to him from heaven and commanding him to leave his father's house. This he does just in time to avoid destruction.[39]

Since Terah was, in effect, a false-god, Abraham's act of leaving his father's house was an act of faith. Jesus, on the other hand, was the Son of the True God and must return to his Father's house. When Abraham left his father's house – the house of a false god – he remained in the land of his sojourn. But Jesus cannot remain in the land of his sojourn; He must return to His Father's house – the house of the one true God. The non-eschatological view of John 14 misses this perspective on the Father's house.

In another example, Rachel leaves her father's house and takes with her the household gods (Gen 31:30, 34). This indicates that the household of Abraham's father never did forsake its attachment to false worship. Furthermore, Rachel, though leaving in body, remained attached in spirit. Some time later, God commands Jacob to get rid of these false gods (35:2).

Other verses relevant to leaving or returning to one's father's house include the following:

- Gen 20:13 (בֵּית אָבִי beit avi; LXX τοῦ οἴκου τοῦ πατρός μου tou oikou tou patros mou) Abraham explains to Abimelech that he had wandered from his father's house.

- Gen 24:7 (בֵּית אָבִי beit avi; LXX τοῦ οἴκου τοῦ πατρός μου tou oikou tou patros mou) Abraham cautions his servant not to take Isaac back to Mesopotamia to find a bride, but rather that the servant should go there to fetch a bride for Isaac. Since God had taken Abraham from his father's house, neither he nor Isaac should return there (also vv. 38, 40).

- Gen 28:21 (בֵּית אָבִי beit avi; LXX τὸν οἶκον τοῦ πατρός μου ton oikon tou patros mou)

Jacob, when fleeing from Esau to Mesopotamia, stops at Bethel and pledges to return to his father's house (i.e. Canaan) in peace some day.

- Gen 38:11 (בֵּית אָבִיהָ ,בֵית־אָבִיךְ veit-avich, beit aviyah; LXX τῷ οἴκῳ τοῦ πατρός σου, τῷ οἴκῳ τοῦ πατρὸς αὐτῆς to oiko tou patros sou, to oiko tou patros autes)

After the incident with Er and Onan, Judah's sons, Er's widow, Tamar returned to her father's house and was instructed by Judah to remain there until Judah's other son Shelah had grown up and could become her husband.

- Gen 50:22 (בֵית אָבִיו veit aviyv; LXX ἡ πανοικία τοῦ πατρὸς αὐτοῦ he panoikia tou patros autou)

Joseph and his father's house remained in Egypt. This was not their place of origin, nor their place of final destination. The situation makes an interesting contrast to John 14. In John 14, it was Jesus who left His Father's house and was returning to it. Whereas in Genesis 50, the entire father's house (= Israel) had moved to a different location. This relocation became a situation of bondage and slavery, from which they would eventually need God's deliverance. This does not seem to be an appropriate figure on which to base the church's present existence in the world.

- Lev 22:12-13 (בֵּית אָבִיהָ beit aviyah; LXX τὸν οἶκον τὸν πατρικὸν ton oikon ton patrikon)

If a priest's daughter marries a layman, she leaves her father's house and no longer partakes of the food of which the priests partake. However, if she becomes widowed or divorced and has no children, then she may return to her father's house and may partake of the priest's food.

- 1Sam 18:1-4 (בֵּית אָבִיו beit aviyv; not in LXX)

After David had slain Goliath (ch. 17), David's and Jonathan's hearts were knit together. Consequently, Saul took David and “would not let him return to his father's house.”

- Luke 2:49 (τοῖς τοῦ πατρός μου tois tou patros mou)

At the age of 12, when Jesus was found by his parents at the temple in Jerusalem, He replied “Did you not know that I must be in my Father's house?” However, “in my Father's house” may not be the best translation. The term “house” (either οἶκος [oikos] or οἰκία [oikia]) is not even used; instead, a plural neuter article (τοῖς [tois] poss. masc.) occurs before τοῦ πατρός μου (tou patros mou) and may mean something like “about my Father's business,” or “among my Father's people.”

- Luke 16:27 (τὸν οἶκον τοῦ πατρός μου ton oikon tou patros mou)

The rich man, being in Hades, begged father Abraham to send Lazarus to his father's house to warn his brothers about Hades.

It seems best, then, to view Jesus' expression, “My Father's house” not as a reference to cultic temple imagery spiritualized as symbolizing the Church, but rather to heaven as the legitimate place of residence for Jesus, a place to which He must return after His sojourn in the world.

“many mansions”

The Greek word translated here “mansions” occurs only twice in the New Testament. The King James translation has given rise to some faulty views. The English “mansion” today generally gives rise to ideas of a spacious and elaborate home. However, the Greek term (μονή mone) simply means either “an abode” (without any reference to its size) or “'a place of halt' on a journey, 'an inn.'”[40] The translation “mansion” is from the Vulgate mansiones which in ancient times simply meant “an abode, abiding-place.” Tyndale first used the English “mansions,” following the Vulgate, and he was followed by the King James and other early English translations.[41]

Some non-eschatological approaches to this passage understand these abiding places in terms of the only other NT occurrence of the Greek term (μονή mone), John 14:23, “If anyone loves me, he will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and will make a dwelling place with him.” Keener states, “the only other place in the New Testament where this term for 'dwelling places' or 'rooms' occurs is in 14:23, where it refers to the believer as God's dwelling place.”[42] Therefore, Keener and others understand the dwelling places in 14:2 as being a reference to the many believers who will constitute the habitation for God in the new temple, the church.

Well, what of this? Are we who see an eschatological promise justified in taking μονή (mone) in verse 2 in a different sense than in verse 23? I think we are. At first glance, it may seem like sound exegetical principle to establish the meaning of μονή (mone) based on its use elsewhere in the same context; however, this is really an overly simplistic view of how language actually works. It is entirely normal for the same word to bear different senses within the same context, even within the same verse. Each occurrence of a word needs to be examined in terms of its usage in the immediate context. For example, in the following totally fictional account, note how the verb “to run” is used a total of ten times, with widely different senses:

I ran out of ingredients for the salad, so I decided to make a quick run down to the store. While at the store, I left the car engine running while I made my purchase, thinking that I would be right out again. However, while I was in the store, I ran into my good friend Edward who was running for county supervisor. This resulted in my having to endure a somewhat long-winded rundown on how his campaign was running. Finally, fearing that my car would run out of gas, I ran with great haste out to the parking lot and returned home with the car surely running only on fumes.

We have no difficulty distinguishing the different senses of the same word “run” throughout the context of this fictional account. Similarly, when we exegete a Scriptural text, we need to examine the sense of each occurrence of a word in terms of its use in the immediate context. Though in John 14 verses 2 and 23 occur in the same chapter, the contexts are quite different. The issue in verse 2 is the disciples' sorrow over Jesus' departure to be with the Father in heaven (see discussion on the expression “I go” below), but the focus changes in verse 15. Verses 15-24 form a distinct unit in the Upper Room Discourse characterized by the believer's love for Jesus as evidenced by the believer's keeping of Jesus' commandments. Borchert notes: “In contrast to a number of scholars, including Segovia, Beasley-Murray, and Carson, who view 13:31–14:31 as a unit, I regard chap. 14 as clearly divisible after 14:14.”[43]

One way of seeing this topic shift is by noting that the verb “to love” (ἀγαπάω agapao) occurs eight times in verse 15-24, but does not occur once in verses 1-14, and the verb “to keep” (τηρέω tereo) occurs four times in verses 15-24, but does not occur once in verses 1-14. At the beginning of this section on loving Jesus and keeping his commandments is the promise that the Holy Spirit would be given to the believer (verse 16). It is by means of the Spirit's indwelling that the believer is: (1) not left as an orphan (verse 18), and (2) empowered to love Jesus and keep His commandments. It is Jesus' sending of the Spirit to indwell believers that makes us understand μονή (mone) as located in the believer. On the other hand, in verse 2, the location of the μονή (mone) is fixed by where we understand the “Father's house” to be. Or, as noted by Borchert, “the concept of dwelling is actually focused in two different directions: in the first the disciples are to gain their dwelling in the divine domain, and in the second the persons of the Godhead come to dwell in the disciples.”[44]

I have argued above that it is best to see the Father's house as located in heaven. In fact, as Köstenberger notes, the concept of these dwelling places as living quarters attached to the Father's residence in heaven is well suited to the customary imagery of the day:

In Jesus' day many dwelling units were combined to form an extended household, it was customary for sons to add to their father's house once married, so that the entire estate grew into a large compound centered around a communal courtyard. The image used by Jesus may also have conjured up notions of luxurious Greco-Roman villas, replete with numerous terraces and buildings situated among shady gardens with an abundance of trees and flowing water. Jesus' listeners may have been familiar with this kind of setting from the Herodian palaces in Jerusalem, Tiberias, and Jericho.[45]

Further, as I will argue below, Jesus' statement “I go to prepare a place for you” is best taken as a reference to Jesus' departure from earth at the ascension to begin His activity in heaven. Thus, the μονή (mone) of verse 2 should be seen as a place of abode fixed in heaven where Jesus will one day bring His disciples.

Another erroneous attempt to establish the meaning of μονή (mone) seeks a meaning based on the use of the cognate verb μένω (meno) in John's writings. Standard works on exegesis and hermeneutics caution against such etymologizing.[46] Typical of this approach is Gundry,

... “abiding” [μένω] in a spiritual sense forms a leading motif throughout the Upper Room Discourse: “the Father abiding in Me” (14:10); “He [the Comforter] abides with you, and will be in you” (14:17); “abide in Me, and I in you ... abides in the vine, ... abide in Me” (15:4); “if anyone does not abide in Me, ... (15:6); “if you abide in Me, and My words abide in you, ...” (15:7); “abide in My love” (15:9); “you will abide in My love; even as I ... abide in His love” (15:10). Jesus could hardly have made it clearer that the abode [μονή] of a disciple in the Father's house will not be a mansion in the sky, but a spiritual position in Christ. The larger context of Johannine literature bears out the same thought. See John 6:56; 1 John 2:6, 10, 14, 24, 27, 28; 3:6, 9, 17, 24; 4:12, 13, 15, 16.[47]

The error here is in trying to define the noun μονή (mone) based on the meaning of the cognate verb μένω (meno). Though cognates are sometimes related in meaning, this is by no means guaranteed. And when it comes to differentiating nuances of meaning (e.g., “spiritual dwellings” vs. “localized dwellings”), such etymologically based reasoning is tenuous at best, and is certainly not based on sound linguistic principles. The immediate context surrounding John 14:2 calls for a localized sense to the word μονή (mone), as was also true with the expression “the Father's house.”

One further note on the sense of μονή (mone) is warranted. Some critics of the pretribulational rapture position have argued that it makes no sense for Jesus to spend two millennia in heaven preparing mansions for believers if those believers will only inhabit these mansions for seven years. This argument is based in part on a misunderstanding of what the term “mansions” represents. Though the term μονή (mone) is capable of bearing a rather wide semantic range of various types of dwelling places, one confirmed sense in Classical literature is that of a “stopping-place,” a “station.”[48] Thus, a place for a seven-year stay before the millennium is entirely within the scope of the semantic range for μονή (mone).[49] Colin Brown concurs with this idea:

... perhaps the meanings which come closest to the 2 instances in the NT are a place of halt on a journey, an inn (Pausanias, 10, 31, 7), a watch-house in a police district (E. J. Goodspeed, Greek Papyri from the Cairo Museum, 1902, 15, 19), a hut for watching in a field (J. Maspero, Papyrus Grecs d'époque Byzantine, 1911 ff., 107, 10).... monē may represent some form of the Aram. 'wn',[50] meaning a night-stop or resting place on a journey (cf. R. E. Brown, The Gospel according to John, II, Anchor Bible, 1971, 618).[51]

A brief excerpt from Pausanias in his Second Century Description of Greece well illustrates this meaning:

παρὰ δὲ τῷ Μέμνονι καὶ παῖς Αἰθίοψ πεποίηται γυμνός, ὅτι ὁ Μέμνων βασιλεὺς ἦν τοῦ Αἰθιόπων γένους. ἀφίκετο μέντοι ἐς Ἴλιον οὐκ ἀπ᾽ Αἰθιοπίας ἀλλὰ ἐκ Σούσων τῶν Περσικῶν καὶ ἀπὸ τοῦ Χοάσπου ποταμοῦ, τὰ ἔθνη πάντα ὅσα ᾤκει μεταξὺ ὑποχείρια πεποιημένος: Φρύγες δὲ καὶ τὴν ὁδὸν ἔτι ἀποφαίνουσι δι᾽ ἧς τὴν στρατιὰν ἤγαγε τὰ ἐπίτομα ἐκλεγόμενος τῆς χώρας: τέτμηται δὲ διὰ τῶν μονῶν ἡ ὁδός.

Beside Memnon is depicted a naked Ethiopian boy, because Memnon was king of the Ethiopian nation. He came to Ilium (Troy), however, not from Ethiopia, but from Susa in Persia and from the river Choaspes, having subdued all the peoples that lived between these and Troy. The Phrygians still point out the road through which he led his army, picking out the shortest routes. The road is divided up by halting-places.[52]

If John used μονή (mone) in a sense similar to that of Pausanias, then he would have Jesus describing the dwelling places in heaven as temporary places of abode where we await Christ's return to earth in power and great glory. Jesus' meaning, then, is simply that there is plenty of room in heaven for all who will believe in Him following His departure from the earth.

“I go”

What is the intended destination of this departure? At issue here is whether Jesus was referring primarily to His death or to His ascension. Some who express a non-eschatological interpretation insist that in the Upper Room Discourse Jesus' departure is a reference to His death by crucifixion. For instance:

Jesus' statement that he is going to the Father to prepare a place for his disciples continues his answer to Peter's questions (13:36-37). Peter has rightly taken Jesus to mean that he is going to his death, but his death is also the way to the Father. How Jesus' death provides an access to himself and to God becomes a major theme of the farewell discourses.[53]

But this seems to be missing the point. Jesus' main point here is not to teach the way to positional righteousness, but to show the way of entrance to heaven. To be sure, only those who are positionally justified will find such entrance, but the primary point here is not immediate and personal; rather, it is eschatological and local. To understand Jesus' language of “going” here, it is important to notice that throughout the Gospel of John there is a significant sub-theme of “coming and going.” The general outline of this theme is as follows:

- In eternity, both Jesus and the Father shared equal glory with each other in heaven, 1:1; 8:58; 17:5.

- At the incarnation, the Father sent Jesus from heaven to the earth to fulfill the Father's will, 6:14, 33, 38, 51; 8:14-16, 21-23; 13:3; 16:27-28, 30; 17:8, 18, 23.

- In the death-resurrection-ascension event, Jesus returns to heaven once again to be glorified in the Father's presence, 6:62; 7:33-34; 8:14; 13:1, 3, 33, 36-37; 14:1-7, 12, 28-29; 16:5-7, 28; 17:1, 11, 13, 24.[54]

When John 14:2 is viewed against the backdrop of this prevailing theme, it seems obvious that Jesus was referring not merely to His departure by death, but to his departure from the earth at the ascension and His subsequent arrival in heaven to be glorified once again in the Father's house. If this is so, then His coming cannot be equated with His post-resurrection appearances, and His receiving of the disciples to Himself is not a receiving of Christians into the mystical body of Christ, but a receiving of Christians to a location apart from the earth – the location where He is being glorified alongside the Father, indeed heaven itself.

“to prepare”

Sometimes the effort to de-localize the promise takes the form of an argumentum reductio ad absurdum, as when Borchert states, “The Gospel of John is not trying to portray Jesus as being in the construction business of building or renovating rooms. Rather, Jesus was in the business of leading people to God.”[55] Well, what did Jesus mean when He said that He would prepare a place for the disciples? “To prepare” (ἑτοιμάζω, hetoimazo) does not necessarily mean to build or construct an edifice. The verb is frequently used of making preparations in advance of someone's arrival. Philemon was to prepare a lodging for Paul (Philemon 22). ἑτοιμάζω (hetoimazo) is used especially of preparations for a meal (Mt 22:4; 26:19; Mk 14:16; Lk 17:8; 22:13).[56] In this connection, Neyrey's comment is interesting:

We may recall how Jesus, the day before (Mark 14.12-16) had sent two of his disciples ahead to secure “a large room upstairs” for the Last Supper. They did not 'know the way,' but had to follow the owner. Arriving, they found everything 'prepared' as Jesus had said. It looks as if here Jesus has made the disciples' journey of the previous day into a parable of “eternity” in which the upper room foreshadows the home of God with its many habitations.[57]

The idea of God's going before His people to prepare a place of rest for them is not foreign to the Scriptures. In Numbers 10:33 The ark (God's presence) went before the children of Israel to seek out a place of rest for them. In Hebrews 6:20 Jesus, our forerunner, has entered into heaven to serve as our high priest. Thus, the preparations referred to likely include such things as preparing the wedding feast for the bride of the Lamb, and daily intercessory prayers of Christ before the throne of God on behalf of Christians.

“a place”

Some interpreters who refuse to see this as an eschatological promise of the rapture want to understand the passage in spiritual and individual terms, rather than local and universal. For example, Hauck says that this passage has in view

... individual rather than universal and eschatological salvation. Salvation consists in union with God and Christ. This takes place through the immanence of God and of Christ in believers and through the taking of believers home to Christ and to God.... The idea of heavenly dwellings of the righteous has its roots in Persian belief, and from here it penetrated into later Judaism, so that the older conception of sheol was essentially reconstructed.... Acc. to [9th cent. Talmudic] Tanch[uma] ... each of the righteous has his own dwelling place (מָדוֹר) in Paradise.”[58]

Such attempts to de-localize Jesus' reference to a “place” result in such nonsensical statements as we find in Comfort and Hawley,

When Jesus said he was going to prepare a place for the disciples in the Father's house, could he not have been suggesting that he himself was that house? Did not the Father live in him and he in the Father? The way for the disciples to dwell in the Father would be for them to come and abide in the Son. In other words, by coming into the one who was indwelt by the Father, the believers would come simultaneously into the indweller, the Father.... Gundry observed that the many rooms are not “mansions in the sky but spiritual positions in Christ, much as in Pauline theology.... Jesus was preparing the way through himself to the Father. The destination is not a place but a Person.”[59]

If this were the case, then Jesus' going to prepare a place is merely a “going” to himself, which is really not a “going” at all, nor is it really to a place! The vocabulary of John 14:1-4 is heavily localized. Note the terms “Father's house” (ἡ οἰκία τοῦ πατρός he oikia tou patros), “dwelling places” (μοναὶ monai), “a place” (τόπος topos) “where I am” (ὅπου εἰμὶ ἐγὼ hopou eimi ego), and “where I go” (ὅπου ἐγὼ ὑπάγω hopou ego hupago).[60] Jesus could scarcely have used more specifically localized language. Surely, He was referring, not to the spiritual sphere of individualized salvation, but to a location in heaven where He intended to take His disciples in the great eschatological event we refer to as the rapture.[61]

Verse 3

“I will come again”

One non-eschatological approach to this passage understands the coming to be a coming of Christ to His children at death.[62] This seems unlikely. As Ice has commented, “The Bible never speaks of death as an event in which the Lord comes for a believer, instead, Scripture speaks of Lazarus 'carried away by the angels to Abraham's bosom' (Luke 16:22). In the instance of Stephen the Martyr, he saw 'the heavens opened up and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God' (Acts 7:56).”[63] Furthermore, the adverb “again” (πάλιν palin) implies that this coming will be a one-time event like the first coming was, not many comings repeated over and over every time a believer dies.[64]

Others have argued that the present tense ἔρχομαι (erchomai) suggests a sense of immediacy about this coming, and though it may be a future coming, it could not be a distant future coming (like 2,000 years). For example, Comfort and Hawley: “The Greek here is in the present tense and should properly be translated 'I am coming,' showing the immediacy of the Lord's return. His coming to them again would be realized in a short while.”[65] So, the argument continues, the present tense fits much better with a coming that was fulfilled either in Christ's post-resurrection coming to the disciples, or in His coming at Pentecost in the Person of the Holy Spirit.

In the first place, this explanation of the present tense is faulty. The futuristic use of the present does not denote near future, as opposed to distant future. Rather, it presents a future event confidently and vividly without reference to the length of the intervening time. Blass, DeBrunner and Funk, state that the futuristic use of the present is used, “in confident assertions regarding the future....” and that, “In prophecies it is very frequent in the NT. It is hardly entirely accidental that the verb ἔρχομαι figures strongly in this usage (cf. especially ὁ ἐρχόμενος 'the one who is to come [the Messiah]' Mt 11:3; cf. v. 14 Ἠλίας ὁ μέλλων ἔρχεσθαι, 17:11 Ἠλ. ἔρχεται).” [66] Gromacki puts it this way, “The choice of the present tense rather than the future in a prophetic context probably implies an ever-present possibility of fulfillment, or imminency.”[67]

What appears absolutely to rule out both the post-resurrection appearances and the Pentecostal advent of the Holy Spirit as fulfillments of Jesus' promise here, are two other sayings of Christ. The first is Christ's saying to Peter at the close of the Gospel of John, one of the last of the post-resurrection appearances.[68] Having just restored Peter to discipleship and predicted his martyrdom (21:15-19), Peter inquires about the future of John. Jesus replies, “If I want him to remain until I come, what is that to you?” The expression “until I come” likewise uses the present tense in reference to a future event (ἕως ἔρχομαι heos erchomai). Clearly, this future event cannot be a reference to the post-resurrection appearances of Christ, and apparently refers to an event that is future to Peter's martyrdom. This seems to make it clear that the promise of Jesus' coming in the Gospel of John refers to a coming well in the future to the Day of Pentecost.

Secondly, approximately sixty years after the crucifixion and resurrection, Jesus still speaks of a future coming using the exact same present tense verb (ἔρχομαι) seven times in the Book of Revelation (2:5, 16; 3:11; 16:15; 22:7; 22:12; 22:20). In Revelation, with both the resurrection and the coming of the Spirit at Pentecost long past, the promise is clearly not referring to a post-resurrection appearance or to Pentecost, but to an eschatological coming. Since in both the Upper Room Discourse, in Jesus' private words to Peter, and in the Book of Revelation we are dealing with the same author (John) and the same speaker (Jesus), we have good reason to see a parallel between the “I am coming” of John 14:2 with the “I am coming” to Peter and in Revelation.

In addition, it should be remembered that in the upper room, Jesus probably spoke in Aramaic. Aramaic does not have a “present tense” per se, only a perfect tense and an imperfect tense. The Greek present is not likely a translation of an original Aramaic perfect tense. More likely, the Greek present translates either an original imperfect, which would not have signified any distinction between an immediate future versus a distant future, or a participle, which could have the same implications as the imperfect. If we remember that Jesus and the disciples had just finished singing Psalms 118, it would be a reasonable assumption that the present tense ἔρχομαι (erchomai, “I come”) actually reflects the Hebrew Qal participle הַבָּא (haba' “he who comes” Ps 118:26). Jesus would therefore have been saying something like, “I, the blessed one who is coming in the name of the Lord, will receive you to myself....” Assuming that “come” refers to Psalms 118:26 also helps to explain the adverb “again.” Psalms 118 ultimately looks to a fulfillment in the Day of the Lord and the millennial kingdom.[69] Jesus had come to Israel offering the kingdom. The disciples had believed that Jesus was the “coming one,” but Jesus had not delivered the kingdom. Having come once, Jesus now says that he will come again. It is at this next coming that the Day of the Lord will be ushered in and the kingdom will surely be set up without further delay.

“receive you to myself ... where I am”

Non-eschatological views hold that “to myself” means into the body of Christ. This requires the following sequence:

- I go to the Father (death, resurrection, ascension)

- I come again (at salvation or at Pentecost)

- I receive you unto myself (Spirit baptism – entrance into the body of Christ)

If this is what Jesus intended, then Jesus receives his followers to a different locale than where he went (He went to heaven, but receives them into the church). It also seems to require that the “going away” of verse 4 (ὑπάγω hupago, to the body of Christ) must be different than the “going away” of verse 2 (πορεύομαι poreuomai, to the Father's house). The change in vocabulary (πορεύομαι poreuomai to ὑπάγω hupago) might appear to justify this change of locus, but an examination of how John uses ὑπάγω (hupago) argues against the position. BAGD notes that ὑπάγω (hupago) is used especially of going “home.”[70] In the context of John 14 the “home” in view would seem to be the Father's house, and this is borne out by Jesus' earlier usage of ὑπάγω (hupago) in His conversation with the disciples: “Jesus then said, 'I will be with you a little longer, and then I am going (ὑπάγω hupago) to him who sent me'” (Jn 7:33).[71]

If the “going away” of verse 4 is a going to the Father's house (=heaven) then it must be the same as the “going away” of verse 2, and the change in terms is merely stylistic, not semantic. This being the case, Jesus is promising to take the disciples to the same place where He is departing, viz. the Father's house. Where will He take them? He said He would take them “where I am.” Where exactly is that? Brindle answers the question as follows:

Two clues help answer this question. First, Jesus' double reference to “preparing a place for them” in heaven is irrelevant (even worthless) information if He did not intend to take them there. The foregoing context thus requires the conclusion that He intends to take them to heaven—where He “will be” (εἰμὶ [eimi] is also a futuristic present here). Second, Jesus then said, “You know the way where I am going” (v. 4). Unless Jesus was being intentionally devious, it must be assumed that He was still speaking of heaven. In fact, following Thomas's question about the way (v. 5), Jesus candidly stated that no one is able to go “to the Father” except through Him (v. 6).”[72]

Conclusions and Implications

From the earliest period in the history of interpretation, Christians have looked at the Lord's promise in John 14:1-3 as an eschatological promise of Christ's return to take His children to a heavenly home where they would be rewarded. Since the destination points to a venue in heaven, not earth, the promise cannot point to a posttribulational rapture and is most consistent with a pretribulational rapture. In more recent times, however, there have been attempts to “de-eschatologize” this precious promise. If the promise could be shown to be non-eschatological, then an important support for the pretribulational rapture would be removed. These non-eschatological views have included: Christ's post-resurrection appearances, the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, Christ's coming to the individual believer at salvation, Christ's coming to the individual believer at death, and Christ's coming to the believer at any time of need in answer to prayer. However, we have shown that there are serious problems associated with the various non-eschatological views of this promise. The problems with a supposed non-eschatological context for the Upper Room Discourse were shown to be irrelevant in light of the clearly eschatological context of the conclusion of the Passover Seder, and the specific language of verses 2-3 is entirely consistent with the promise of a pretribulational rapture of the church. So, while some might suggest that the believer has already arrived at the Father's house, our word of encouragement is: No, we're not there yet. Just be patient, we'll be there soon.

“I will come again.”

“Amen. Come, Lord Jesus.”

Appendix 1: John 14:1-3 and 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18

From “The Rapture and John 14” by Dr. Thomas Ice

|

John 14:1-3 trouble v. 1 believe v. 1 God, me v. 1 told you v. 2 come again v. 3 receive you v. 3 to myself v. 3 be where I am v. 3 |

1 Thessalonians 4:13-18 sorrow v. 13 believe v. 14 Jesus, God v. 14 say to you v. 15 coming of the Lord v. 15 caught up v. 17 to meet the Lord v. 17 ever be with the Lord v. 17 |

Appendix 2: “Coming and Going” a Sub-Theme in the Gospel of John

John 1:1 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

John 6:14 Therefore when the people saw the sign which He had performed, they said, “This is truly the Prophet who is to come into the world.”

John 6:33 “For the bread of God is that which comes down out of heaven, and gives life to the world.”

John 6:38 “For I have come down from heaven, not to do My own will, but the will of Him who sent Me.

John 6:51 “I am the living bread that came down out of heaven; if anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever; and the bread also which I will give for the life of the world is My flesh.”

John 6:62 “What then if you see the Son of Man ascending to where He was before?

John 7:33-36 Therefore Jesus said, “For a little while longer I am with you, then I go to Him who sent Me. 34 “You will seek Me, and will not find Me; and where I am, you cannot come.” 35 The Jews then said to one another, “Where does this man intend to go that we will not find Him? He is not intending to go to the Dispersion among the Greeks, and teach the Greeks, is He? 36 “What is this statement that He said, 'You will seek Me, and will not find Me; and where I am, you cannot come'?”

John 8:14-16 Jesus answered and said to them, “Even if I testify about Myself, My testimony is true, for I know where I came from and where I am going; but you do not know where I come from or where I am going. 15 “You judge according to the flesh; I am not judging anyone. 16 “But even if I do judge, My judgment is true; for I am not alone in it, but I and the Father who sent Me.

John 8:21-23 Then He said again to them, “I go away, and you will seek Me, and will die in your sin; where I am going, you cannot come.” 22 So the Jews were saying, “Surely He will not kill Himself, will He, since He says, 'Where I am going, you cannot come'?” 23 And He was saying to them, “You are from below, I am from above; you are of this world, I am not of this world.

John 8:58 Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, before Abraham was born, I am.”

John 13:1 Now before the Feast of the Passover, Jesus knowing that His hour had come that He would depart out of this world to the Father, having loved His own who were in the world, He loved them to the end.

John 13:3 Jesus, knowing that the Father had given all things into His hands, and that He had come forth from God and was going back to God,

John 13:33 “Little children, I am with you a little while longer. You will seek Me; and as I said to the Jews, now I also say to you, 'Where I am going, you cannot come.'

John 13:36-37 Simon Peter said to Him, “Lord, where are You going?” Jesus answered, “Where I go, you cannot follow Me now; but you will follow later.” 37 Peter said to Him, “Lord, why can I not follow You right now? I will lay down my life for You.”

John 14:1-7 “Do not let your heart be troubled; believe in God, believe also in Me. 2 “In My Father's house are many dwelling places; if it were not so, I would have told you; for I go to prepare a place for you. 3 “If I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and receive you to Myself, that where I am, there you may be also. 4 “And you know the way where I am going.” 5 Thomas said to Him, “Lord, we do not know where You are going, how do we know the way?” 6 Jesus said to him, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father but through Me. 7 “If you had known Me, you would have known My Father also; from now on you know Him, and have seen Him.”

John 14:12 “Truly, truly, I say to you, he who believes in Me, the works that I do, he will do also; and greater works than these he will do; because I go to the Father.

John 14:28-29 “You heard that I said to you, 'I go away, and I will come to you.' If you loved Me, you would have rejoiced because I go to the Father, for the Father is greater than I. 29 “Now I have told you before it happens, so that when it happens, you may believe.

John 16:5-12 “But now I am going to Him who sent Me; and none of you asks Me, 'Where are You going?' 6 “But because I have said these things to you, sorrow has filled your heart. 7 “But I tell you the truth, it is to your advantage that I go away; for if I do not go away, the Helper will not come to you; but if I go, I will send Him to you. 8 “And He, when He comes, will convict the world concerning sin and righteousness and judgment; 9 concerning sin, because they do not believe in Me; 10 and concerning righteousness, because I go to the Father and you no longer see Me; 11 and concerning judgment, because the ruler of this world has been judged. 12 “I have many more things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now.

John 16:16-18 “A little while, and you will no longer see Me; and again a little while, and you will see Me.” 17 Some of His disciples then said to one another, “What is this thing He is telling us, 'A little while, and you will not see Me; and again a little while, and you will see Me'; and, 'because I go to the Father'?” 18 So they were saying, “What is this that He says, 'A little while'? We do not know what He is talking about.”

John 16:27-28 for the Father Himself loves you, because you have loved Me and have believed that I came forth from the Father. 28 “I came forth from the Father and have come into the world; I am leaving the world again and going to the Father.”

John 16:30 “Now we know that You know all things, and have no need for anyone to question You; by this we believe that You came from God.”

John 17:8 for the words which You gave Me I have given to them; and they received them and truly understood that I came forth from You, and they believed that You sent Me.

John 17:11 “I am no longer in the world; and yet they themselves are in the world, and I come to You. Holy Father, keep them in Your name, the name which You have given Me, that they may be one even as We are.

John 17:13 “But now I come to You; and these things I speak in the world so that they may have My joy made full in themselves.

John 17:18 “As You sent Me into the world, I also have sent them into the world.

John 17:23 I in them and You in Me, that they may be perfected in unity, so that the world may know that You sent Me, and loved them, even as You have loved Me.

John 21:22 Jesus said to him, “If I want him to remain until I come, what is that to you? You follow Me!”

Works Cited

Bauer, Walter, William Arndt, F. Wilbur Gingrich and Frederick W. Danker. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature : A Translation and Adaptation of the Fourth Revised and Augmented Edition of Walter Bauer's Griechisch-Deutsches Worterbuch Zu Den Schriften Des Neuen Testaments Und Der Ubrigen Urchristlichen Literatur. 2d ed., rev. and augmented. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

Blass, Friedrich Albert Debrunner and Robert Walter Funk. A Greek Grammar of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961.

Borchert, Gerald L. John 12-21, The New American Commentary, New International Version. Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2002.

Brindle, Wayne A. “Biblical Evidence for the Imminence of the Rapture” Bibliotheca Sacra 158:630, April – June 2001.

Brown, Colin gen. ed. The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1975.

Burge, Gary M. John: From Biblical Text ... to Contemporary Life. The NIV Application Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2000.

Calvin, John. Calvin's Commentaries, Vol XVIII, John 12-21; Acts 1-13. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Carroll, John T. et al. The Return of Jesus in Early Christianity. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2000.

Carson, D. A. Exegetical Fallacies. Grand Rapids: Paternoster; Baker Books, 1996.