Interpreting Texts on End-Time Geophysical Catastrophes

Charles A. Clough

“There will be great tribulation, such as has not been since the beginning of the world until this time, no, no ever shall be. . . .Immediately after the tribulation of those days the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not gives its light; the stars will fall from heaven, and the powers of the heavens will be shaken.”

Matthew 24:21,29 [1]

“I looked when he opened the sixth seal, and behold, there was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became like blood. And the stars of heaven fell to the earth. . . .Then the sky receded as a scroll when it is rolled up, and every mountain and island was moved out of its place.”

Revelation 6:12-14

Introduction.

Should we interpret texts that describe cosmic geophysical catastrophes as referring to actual phenomena or as merely figurative language referencing socio-political upheavals?[2] Or, perhaps, should we interpret them as figurative language without an actual historical referent at all but as emotionally stimulating imagery of God’s grandeur in judging mankind? All these options are currently on the table in the evangelical community today. Unfortunately, one cannot delve into the relevant hermeneutical details without immediately becoming entangled in a wide web of background issues. It has become apparent to me in reading the discussions of the last century—both within and without the evangelical community—that background issues are often ignored or uncritically passed over. By background issues I mean reliance upon particular cosmologies, epistemologies, and language theories.

I attempt in this paper to explore briefly some figurative interpretation methodology used to interpret language of biblical cosmic catastrophes in cases of liberal and evangelical commentators. I do so from the perspective of their apparent ideological assumptions and conclude that these prior ideologies have one or more problems for understanding the Word of God: (1) unjustified faith in the virtual infallibility of so-called “scientific” cosmologies to replace the prima facie biblical cosmology subverts the ethical core of the biblical story; (2) uncritically accepted Kantian-derived epistemologies are a useless gambit to salvage biblical faith; and (3) usage of recently-articulated notions of community-contextual limits on language without metaphysical correction cannot convey the full scope of special revelation.

Finally, I attempt to provide suggestions for a biblically-based hermeneutic of the language of end-time geophysical catastrophes.

Liberalism’s figurative language interpretations of cosmic catastrophes

As everyone who has taken an Introduction to the Old Testament course knows, the liberal schools of higher criticism have inevitably used a figurative language interpretation technique to explain away textual references to anything contradicting modern scientific cosmology. In their view figures of cosmic upheaval refer to mythical imagination often borrowed by the Israelites from their pagan neighbors.

The Bible’s allegedly “mythical” view of nature automatically filtered out by hermeneutics.

The pioneer of form criticism, Hermann Gunkel, writing in the nineteenth century after Lyell and Darwin, insisted that the Hebrews borrowed cosmological myth from the Babylonians which they then altered to fit their monotheist vision of the exodus. Passages like Psalm 89:9-11

You rule the raging of the sea’

When its wave rise, You still them.

You have broken Rahab in pieces, as one who is slain;

You have scattered Your enemies with Your mighty arm.

The heavens are Yours, the earth also is Yours;

The world and all its fullness, You have founded them.

refer to ancient pagan stories of the triumph of creation over chaos (Rahab being a mythical sea monster figure) which the author applies to the exodus event—not to describe an extraordinary event but to depict a mundane one that must be embellished with cosmic imagery.[3]

Shailer Matthews, liberal social reformer in the early twentieth century, knew that motivation for social work required the vision of the coming Kingdom of God in the biblical prophetic texts. But having faith in the virtual inerrancy of scientific cosmology he could not bring himself to believe in their historicity. Thus he wrote, “The prophecies of the Old Testament are not highly ingenious puzzles to be worked out—always mistakenly, in charts, diagrams, and ‘fulfillments.’ They are the discovery of [God’s] laws in social evolution. The pictures of the ‘last things’ in the NT are not scientific statements but figures of speech expressing everlasting spiritual realities.”[4]

Terence E. Fretheim, recent Old Testament book editor for the Journal of Biblical Literature, comments that the actual exodus event is unknowable and unawesome but becomes so when seen “in greater depth” such as in the poetic song of Exodus 15: “only when one hears the interpretation does one know fully what in fact one has experienced”.[5] Obscure and naturalistic events must be described in glorified language since locally-bound historical and redemptive categories aren’t strong enough to be the stuff for universal theology. And the means of glorification is use of cosmic imagery.[6]

For this liberal tradition the cosmic catastrophes that accompany both judgment and the coming new heavens and earth cannot be literal because taken at face value they imply a “mythical” cosmology utterly and hopelessly at odds with the placid naturalism of “scientifically true” cosmology. Proper hermeneutics, therefore, must include a filter that automatically interprets biblical language of physical upheaval as figurative.

A critique of the rationale for hermeneutical dependence upon modern cosmology.

Thanks to a rising tide of scientifically trained creationists more material exists than ever before concerning the nature of studying the past with scientific methodologies. The well informed exegete today has no excuse for blindly accepting the culture’s evolutionary, naturalistic view of an undisturbed natural environment.

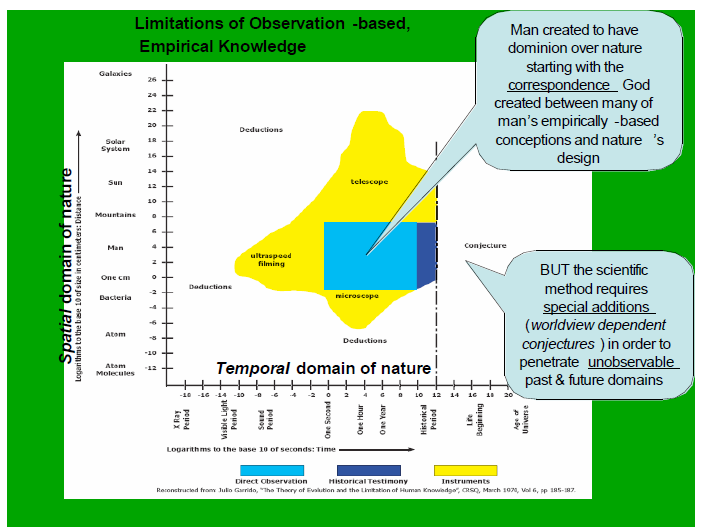

To avoid attributing virtual infallibility to it exegetes need to understand the limitations of the scientific method when applied to discovering past events. Laboratory science is one thing; historical science is quite another (a distinction callously glossed over in modern education). Essential to empirically-based knowledge are observations and measurements. Figure 1 is a “map” of the limitations of observational data. The x-axis depicts time scale rather than linear time, i.e., the farther to the right, the larger the time scale of the data observed. Similarly, the y-axis depicts space-scale rather than linear measurement, i.e., the farther upward, the larger the space scale of the data observed. The inner rectangle pictures what any individual can observe during his or her lifetime without special instrumentation. With such instrumentation, one can observe very fast events (high-speed photography), very small objects (microscopy), and very large objects (telescopy). However, and this is the crucial point, directly trying to observe something over a duration longer than one’s lifespan or longer than record-keeping human history is impossible. If one discards the Bible’s claim of eyewitness observations of the past, one is thereby left to infer what observations of the past might look like. This method of generating surrogate observations has to make conjectures about the physical environment such as the uniformity of so-called natural law throughout all space and time and the cosmological principle that any particular region of the universe looks the same as any other.[7] These extra requirements of historical science distinguish it from laboratory science. One has to reflect critically on attributing the credibility of the latter to the former.

Figure 1. Limitations of empirical data. X-axis and Y-axis are time and spatial “size” of data. Instrumentation helps observations of small and large spatial size as well as observations of very brief events (small time “size”), but cannot help observations of events on time scales exceeding that of direct human observation both into the future and into the past. Historical science, therefore, must rely upon non-scientific conjectures concerning the nature of the physical universe.

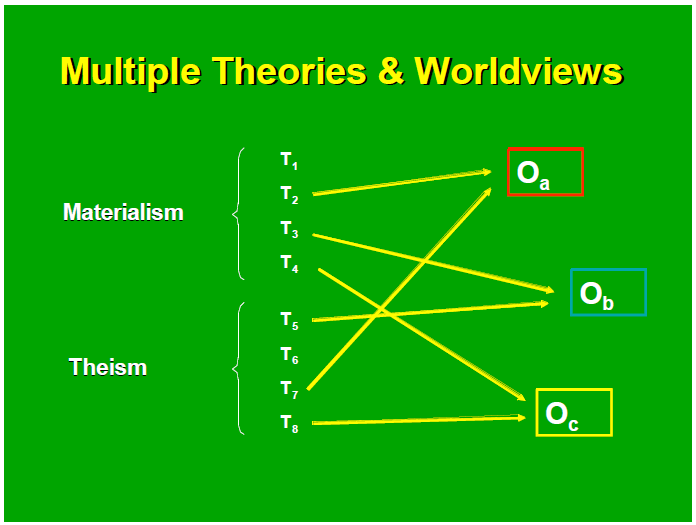

Besides the problem of applying a methodology intended for study of repeatable phenomena to study non-repeatable phenomena, violations of basic logical laws are often overlooked in analysis of empirical data (another feature of scientific investigation casually treated, if at all, in modern education). In logic we observe the statement of inference “if P is true, then Q is true.” This law occurs in all theory testing when P = a [T]heory, and Q = an empirically [O]bserved state-of-affairs. For example, a uniformitarian theory of geophysical processes may imply a certain pattern of igneous and sedimentary rock strata. Common opinion says that if the field data show that such a pattern in fact exists, then the uniformitarian theory must be true. Not so! If the [O]bserved geological state-of-affairs is true, that does not prove that the uniformitarian [T1]heory is true because there could be a catastrophic theory, say T2, such that “if T2 is true, then O is (also) true.” Both these theories imply the same observable situation. Figure 2 presents a case where multiple theories happen to account for some of the same data sets. Here, then, is the problem with common opinion. If there are two or more theories, each of which implies the same state-of-affairs, how do we select the “best” theory?

We have now arrived at the nub of present debate between naturalists and supernaturalists. Each school has its own theory-selection criteria that has nothing to do with the empirical data. Harvard population biologist, Richard Lewontin, let the cat out of the bag in his New York Review of Books discussion of Carl Sagan’s last book:

Figure 2. Multiple theories can exist to account for given observational data sets (Oa, Ob, Oc). One has to depend upon philosophically informed theory-selection criteria. The data sets themselves cannot help decide in such cases.

“Our willingness to accept scientific claims that are against common sense is the key to an understanding of the real struggle between science and the supernatural. We take the side of science in spite of the patent absurdity of some of its constructs, in spite of the tolerance of the scientific community for unsubstantiated just-so stories, because we have a prior commitment, a commitment to materialism. It is not that the methods and institutions of science somehow compel us to accept a material explanation of the phenomenal world, but, on the contrary, that we are forced by our a priori adherence to material causes to create an apparatus of investigation and a set of concepts that produce material explanations, no matter how counter-intuitive, no matter how mystifying to the uninitiated. Moreover, that materialism is absolute, for we cannot allow a Divine Foot in the door.”[8]

Once the theory-selection criteria and the metaphysical presuppositions of historical science are unearthed, we ought to take to heart the biblical warnings that the theophobia of unbelief (as Paul describes in Romans 1:18ff and as Lewontin exhibits) certainly can have a pervasive and idolatrous intellectual influence. Comparison of modern cosmology with ancient pagan cosmology like that which appears in Enuma Elish reveals remarkable parallels. Both utilize a chain-of-being metaphysic; both extrapolate natural processes to perform magical feats like spontaneous generation of life; both depict a very old universe, and both submerge man under nature.[9]

These considerations are no mere intellectual pastimes for the question before us. Three obvious examples come to mind of the impact of cosmology on hermeneutics: (1) how origin of the extra-terrestrial universe impacts the interpretation of Genesis 1, especially the “fourth day puzzle”, as well as all later biblical references to creation from Exodus to Revelation; (2) how the geological history of the earth impacts interpretation of the flood of Genesis 6-8 and all later biblical references to that event; and (3) how the chronology of the second millennium, B.C., impacts interpretation of the exodus and conquest phenomena around which cosmic language is used of the end-time prophecies.[10]

Section summary. A hermeneutic for interpreting cosmic catastrophe texts that starts with a denial of the biblical story necessarily must end in denial of the biblical story. And nowhere in that story is there a greater defiance of all speculative cosmology than the resurrection and ascension of Jesus Christ. Nowhere can it be clearer that to deny literal language of a biblically-reported physical event is to accuse the prophets and apostles of outright perjury (1 Cor 15:15 cf. John 3:12). Figuratively interpreting what Scripture presents as a literal report, therefore, challenges the ethics of biblical religion and thus its entire edifice.[11] Another consequence: discarding the literalness of events in early Genesis throws away valuable data that could solve the philosophic and linguistic dilemmas plaguing biblical studies.[12]

Liberalism’s attempt to salvage theology from figurative language.

If liberal higher criticism sawed off the biblical branch that could have provided a cosmological support to orthodox theology, what other support could be found? Can the teleological vision and ethical tenets of the Bible be saved from the damage figurative interpretation does to its historical testimonies? Fortunately for liberalism, the titular Enlightenment thinker Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) came on the scene and seemed to provide a way out of the dilemma. Ever since his day liberal theology has supported itself by using various derivatives of his epistemology. Let’s examine briefly how liberalism has attempted to save the idea of a judging and saving God without affirming his catastrophic intervention into our physical environment.

Kant to the rescue.

Kant was interested in science and in cosmology in particular. He worked out one of the first modern naturalistic cosmologies, the Nebula Hypothesis. Later, however, he became more and more concerned with preserving a sense of human dignity and moral responsibility against what seemed to be an ever increasing confusion over the place of man in nature. The apparent triggering event in his life was learning about the challenge of empiricist thinking brought by David Hume (1711-1776). Hume raised the question of how we can assume that causality exists in the world when all we have are a finite set of sequential sensations in our mind.

Kant’s philosophical response is very intricate but for the purposes of the present discussion it can be summed up in pointing to his separation of all knowledge into two realms. The phenomenal realm is what we experience through sensation. We can’t know about the world as it really is—whether, for example, causality actually exists “out there.” What we know is the organization our minds place on the stream of sensations so that we can live as though causality exists. The real origin of truth, then, for knowing what we perceive is our mind, not the external world of nature itself and not the God of revealed truth.

So much for our empirical experiences of history. What about God, ethics, and religion? They are all part of Kant’s second realm of knowledge, the noumenal. That realm is what is “really out there” but not knowable in any empirical way. We only have an inner sense that something must be out there to account for our sensations of it. In Van Til’s careful analysis of Kant he writes:

“The field of science seemed to require the idea of necessity while the field of ethics is based upon the notion of freedom. These are exclusive of one another. Yet man is involved in both of them. . . .What Kant is saying is that the scientific principles of necessity are valid. . .but that this validity at the same time implies the limitation of science to the I-it dimension. This validation and limitation of science brings great relief to the modern theologian. He can now commit himself without reserve to the principles of modern science. When he brings the message of Christianity he does not have to enter the realm of science. He does not have to engage in any such debates as have been carried on in the past. . . .It is precisely at this point that we have the origin of much of modern theology. . . .From the Christian point of view we have here the deepest possible rejection of the triune God of Scripture as the self-sufficient subject in relation to whom alone all facts in any realm, lower or higher, have their meaning. In short, in Kant’s position, we have a complete reversal of the covenantal relation in which man, the creature, stands to God. . . .Man instead of God is now the one who ordains its ordinances.”[13] [Emphasis supplied]

Kant argued that although man cannot know God as a Person who reveals himself in space-time history, man needs to have the idea of God to provide a basis for the sense of “oughtness.” Kant’s idea of God is an ethical Ideal or a limiting concept that

“is the projection of the autonomous man. [It and his idea of moral law] are means by which the free personality is seeking to accomplish its great aim of realizing its own ideal of perfect control over nature and perfect happiness in this perfect control. . . .If Kant’s God is to be spoken of as revealing himself, then it must be added that he reveals only what the free man wants this God to reveal.”[14]

This discussion, like the one preceding, is not an academic parlor game. One logical result of Kant’s influence on the practical level is that the ideal of God from the noumenal realm can only give “a certainty of faith and not of knowledge.”[15] Another result is that figurative language becomes a means of giving an appearance of biblical faith while denying its claims in the phenomenal realm of physical history.

Salvaging God’s holiness through figurative interpretation of biblical judgments and deliverances.

Liberal exegesis continually imagines that catastrophic language has to be a projection upon biblical history rather than a description of it. For example in his source analysis of OT texts, Gunkel interprets the following text as a Hebrew adaptation of a pagan dragon myth and the source of material later used by Ezekiel:

You broke the heads of Leviathan in pieces,

And gave him as food to the people in habiting the wilderness.

You broke upon the fountain and the flood;

You dried up mighty rivers. Psalm 74:14-15

Gunkel here thinks that the author of Psalm 74 utilizes mythical material of a water monster being slain and leaving the fluid over the land as his way of explaining the precipitation cycle! My point here isn’t to resurrect a straw man for criticizing figurative interpretation but to show that Gunkel’s focus isn’t at all on the details of Israel’s history. It’s become an exploration in Hebrew religious imagination unconstrained by any experience of God revealing himself in historical experience.

Writing about the same time as Gunkel but considerably more conservative in his theology was Milton S. Terry who is known for his work on hermeneutics. He reacted to the excesses of the biblical criticism of his day which had centered on discovering how biblical texts had come into existence. He wanted to redirect attention back to the message of the resulting canonical text. So he set aside the topics of higher critical investigation for the sake of exegeting the meaning of the texts:

“I have in some instances allowed the claims of a radical criticism, which I am personally far from accepting as established, for the very purpose of showing that the great religious lessons of the scripture in question are not affected by critical opinions of the possible ‘sources,’ and date, and authorship, and redaction.”[16]

However, in discussing the creation narrative Terry reveals a rejection of more than just source criticism; he follows in the liberal tradition of rejecting biblical cosmology en toto. He writes, “The discoveries of science have effectually exploded the old notion of the creation of earth and heavens in six ordinary days” and “we do not believe that Genesis. . .was given to instruct men in astronomy, or geology, or chemistry. . .”[17] Thus he denies the historical factuality of the events in the Genesis 1-11 in contrast to NT authors who repeatedly refer to these “stories” as historical revelation of the nature of man, sin, and other “great religious lessons.”

More directly illustrative for our present purpose is how Terry treats the exodus narrative of the plagues whose imagery “is largely appropriated in the New Testament Apocalypse of John to portray the ‘terrors and great signs from heaven,’ which there figure as trumpets of woe and bowls of wrath.”[18] He discards all discussion of their historicity, preferring to treat such reports of judgment as “the drapery of human conceptions of judgment.”[19] The OT classical prophets’ pronouncements of cosmic judgment upon Gentile nations “so far transcended the immediate occasion as to throw the latter [Chaldean desolation] comparatively out of sight. The judgments and the salvation herein conceived seem rather ideal. . . .”[20]

Not unexpectedly Terry treats the cosmic catastrophes of the 6th seal in Revelation 6:12-17 in the same manner as he treated the OT judgments with similar imagery, viz., judgment limited to the socio-political sphere exclusive of any cosmic component. The ensuing judgment imagery, he notes, comes mostly from the exodus event. And the final vision in Revelation, the catastrophic creation of the new universe, Terry writes, should not be interpreted “as a literal record of historic events. [The vision elements] are to be recognized as symbolical pictures, designed to indicate the ultimate victory of the Christ. . .It is an ideal picture of what the Messiah is and what he does during the whole period of his reign; not of any one particular event of his coming.”[21]

Section summary. We saw above that replacement of biblical cosmology by extra-biblical cosmologies—whether the pagan stories of ancient times or the pagan-like cosmologies of modern times—logically guarantees that every truth connected with the biblical story comes into jeopardy. After uncritically trusting in the virtual infallibility of modern historical science, liberal theologians next uncritically appropriated methodologies derived from Kant’s distinction between the phenomenal realm (historical criticism) and the noumenal realm (limiting concepts of God and moral law). Biblical depictions of history were all problematical—maybe they were true; maybe not. It no longer really mattered as long as the “religious lessons” were extracted from the text.

What went unnoticed, however, was that Kant had replaced God with man. In his view man’s thoughts—including the biblical writers’ religious ideas—arise solely from within. Whatever religious lessons that are derived from the biblical stories in a Kantian perspective must be anthropocentrically-derived. Such lessons would then be nothing more than Hebrew autobiography. Though many godly men like Terry tried to hold on to orthodox theology, their theology was limited to sharing what could only now be Hebrew imagination. More consistent liberals went on to apply the Kantian perspective to the epitome of revelation, the incarnate God-Man. The Ideal religious picture of the Christ became separated from the historical Jesus.

The attempt to salvage theology with some sort of Kantian derivative can only generate an assurance of a faith that “somehow” God is behind the biblical stories but hidden. It cannot generate assured knowledge of the God that publicly shares his thoughts with mankind and validates his promises by detectable historical acts.[22] Faith becomes completely subjective ungrounded on any objective authority external to man.

Evangelicalism’s use of recent language theory in figurative interpretation of cosmic catastrophe texts.

Evangelicals have historically defended the authenticity of the biblical text in the face of liberal abandonment of it. They have been just as diligent to utilize archeological findings in expounding the meaning of it, if not more so, than their liberal counterparts. The crucial difference between the two methodologies centers on where the Scripture intends to be historically true. Liberals can discard historicity wherever it is convenient; evangelicals must adhere to literal interpretation everywhere historicity is expressed. Elsewhere figurative interpretation must be watched for by the careful exegete, especially in poetically-expressed prophetic and so-called apocalyptic literature.[23]

While reading the well-written and widely-used text Plowshares & Pruning Hooks: Rethinking the Language of Biblical Prophecy and Apocalyptic,[24] I couldn’t help noticing the many statements about the limitations of language. Since theologians have shown a tendency to imbibe uncritically alien cosmologies and epistemologies over the past century or two, I wondered about the nature of the theories of language now being used in evangelical hermeneutics. My brief comments on contemporary language theory below will be followed by the effect such theory has on special revelation.

Figurative Language: Features and Functions.

Metaphor’s Three Parts. Central to the use and decoding of figurative language are its features, viz., (1) the figure, (2) the object to which that figure is transferred, and (3) the relationship between them. Metaphorical theory involving these three elements remained pretty much at the level of Aristotle’s Poetics until the 20th century. It has undergone significant development during the past decades. By 1936 I. A. Richards devised an “interaction” theory to understand the third element of metaphor, the relationship. Instead of a mere comparison between the figure and the object, Richards said, “When we use a metaphor we have two thoughts of different things active together. . . whose meaning is a resultant of their interaction.”[25] Figurative language challenges the mind to reconcile the conflict brought about by an unexpected juxtaposition of two disparate thoughts. One of its functions, then, is to trigger deeper thought. This is the function that has provoked much of the recent work to explore what such language shows about man’s thought processes.

The recognized scope of figurative language has greatly expanded. Early on it was recognized that language is filled with dead metaphors no longer recognized as such (e.g., “leg of a table,” “hood of a car”). Also recognized is the ubiquitous metaphor employed by poets for explanation, emotional impact, and aesthetic dressing. The kind of metaphor, however, that has stimulated the most research is the metaphor necessary to express abstractions and other ideas that cannot be directly experienced. Richards writes:

“Language, well-used, does what the intuition of senses cannot do. Words are. . .the occasion and the means of that which is the mind’s endless endeavor to order itself. . ..[Other language theorists] think that the [sensory] image fills in the meaning of the word; it is rather. . .the word which brings in the meaning which the image and its original perception lack.”[26]

More recently another rhetorician, Philip Wheelwright has gone further in making knowledge dependent upon language. He says of metaphor, that it “partly creates and partly discloses certain hitherto unknown, unguessed aspects of What Is.”[27]

Needless to say, some 20th century poets were quick to see the logical conclusion of such language theory. Wheelwright describes how they created “pure poetry” by composing nonsensical word combinations like “Toasted Susie is my ice cream” hoping “in the broad ontological fact that new qualities and new meanings can emerge. . .out of some hitherto ungrouped combination of elements. . . .As in nature new qualities may be engendered by the coming together of elements in new ways, so too in poetry new suggestions of meaning can be engendered by the juxtaposition of previously unjoined words and images.”[28]

Generation of Meaning and Its Communication. Note in the above ideas of language theory that man somehow spontaneously generates meaning like random evolutionary processes supposedly once generated the chemical elements. How is this distinguishable from Kantian epistemology? Meaning springs up spontaneously in the subjectivity of man. Ostensible evangelicals like John Franke at Biblical Seminary have imbibed this same Kantian type of epistemology that comes hidden inside the so-called “speech-act theory” of recent language philosophy. Franke notes that language is not basically descriptive but, like Richardson and Wheelwright, sees it as constructive. And this construction occurs in the context of a linguistic community. [29]

To see why Franke and others say this, we need to remember that literal and figurative language depends upon the use of symbols (marks on paper, gestures, tones of voice, etc.) as well as whole metaphors that carry information from the “sender” to the “receiver.” To successfully convey information, therefore, such symbols and metaphors must have the same meaning attributed to them by sender and receiver. Language theory, however, adds two further propositions: (1) the assignment of meaning is purely an arbitrary act of the “community” of senders and receivers, i.e., the “socio-linguistic community”; and (2) all knowledge of such a community is limited to their situational perspective.

If one accepts both of these claims, then one’s hermeneutics become very tentative. Where to draw the line between literal and figurative is made much more difficult since whatever information is contained in a particular text can only have arisen inside the immediate community of the author in a purely arbitrary fashion. Since we exegetes are not a part of that community, we face the daunting task of having to guess the nature of the arbitrary interaction of the metaphoric symbol and object. The second claim adds an additional complication: how much of the text expresses truths valid for us who live outside that community? Franke, for example, by accepting the propositions of modern language theory, finds himself unable to establish the Christian faith by exegesis alone because of his view of the limitations of language (contra Rom.10:17).[30]

Figurative Language and Special Revelation.

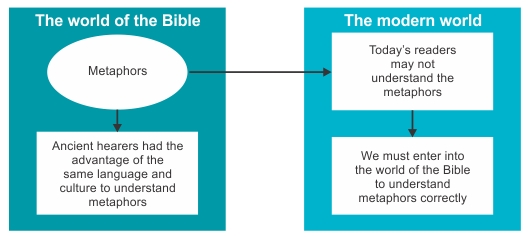

In discussing how to identify figures and metaphoric expressions in prophetic literature Sandy rightly reminds us that most of prophetic literature is poetic and therefore loaded with figurative language. He suggests many fine guidelines to interpret prophetic and apocalyptic literature by trying to understand the original intent of the author within his community. He wishes to avoid sensationalism that dogmatically assumes it knows in advance how each textual detail will be fulfilled. His diagram on page 65 clearly shows the problem of interpreting metaphors. The interpreter of biblical metaphor must somehow “enter into” the socio-linguistic community of the author in order to get clues on determining if a text is a metaphor or not and, if so, its meaning. However, when I read things like the following statements, I began to wonder if there are influences from alien cosmology, epistemology, and language theory in his approach.

Figure 3. Sandy’s depiction of the cultural challenges of interpreting biblical metaphors.

“Language originates in humankind’s fundamental need to communicate.” (p. 25)

“God’s choices [for a language of revelation] were limited. . .the other issue God faced was how to describe heavenly concepts in human language” (p. 26f)

“In a sense prophecy was assigned an impossible task. With language limited to what we have experienced, how can God be described?” (p. 27)

“Under divine empowerment, the prophets created metaphors and similes. . .as best they could.” (p. 28)

“The language of curses and blessings actually originated in ancient Near Eastern culture (p 83)

“Our interpretation of Joel 2:31 many conclude that the meaning of the metaphor is unrelated to the normal meanings of the. . .parts. . .’The moon shall be turned to blood’ designates a time of upheaval, not necessarily any changes in the sky.” (p 168)

“It is likely that these celestial horrors [of Revelation 6:12-14; 8:7,10,12; 9:2; 11:19)] are metaphoric. . . .Everything will be topsy-turvy, and one way to suggest that is to describe the heavens as completely disoriented.” (p 177)

In a work referenced in Plowshares & Pruning Hooks, evangelical Richard Patterson illustrates how texts—eschatalogical and non-eschatological—depicting geophysical catastrophe are to be interpreted figuratively. While he provides a convincing argument that the cosmic language of the exodus “furnished a natural development into the more spectacular, universal, and often ethereal tone that gave impetus to an emerging apocalyptic in the prophets of the pre-exilic and exilic periods”[31], he explains the originating exodus events as ordinary kinds that fit within a placid, uniformitarian view of nature.[32] These rather ordinary environmental happenings are remembered, however, with metaphorical language that is eventually enlarged to “universality and end time.”[33] The exodus imagery became “an ancient myth of deliverance” that provided the impetus for Yahweh Warrior theology.[34] Echoing Sandy, Patterson explains:

“The persistence of these [exodus-type] images strongly suggests that they had become a body of stylized vocabulary that the prophets had at their disposal to express God’s judgment and saving activities. The freedom and variety with which they were utilized suggests further that although they had become a conventional part of eschatological predictions, they are not to be viewed as a blueprint of concrete details relative to end-time events. . . .[35]

While I have little argument with the admonition to be alert for figurative language in prophetic poetry and respect many of the practical rules Sandy has developed, I am uneasy with the free-wheeling use of figurative language to minimize every hint of catastrophic phenomena in Scripture. In a post-Kantian era, I wonder about the validity of a theology involving God as universal judge and savior that so depends upon Hebrew imagination that makes mountains out of molehills. Has something been smuggled in here from theories of how language works inside a linguistic community such that communication into and out of that community is so very limited? Didn’t the God of special revelation design language and the world of perception to have adequate capacity for transfer of his thoughts to man?

There’s another problem with minimizing the dimensions of biblical events in heaven and earth. Only the most casual reader of the Bible could miss what Fretheim calls the “symbiosis between the human and the non-human orders commonly observed in the OT from Genesis 3 on (e.g., Hos 4:1-3; Jer.9:10-16,20-22).”[36] In a day of heightened ecological awareness how can we not take seriously the relationship between man as lord of creation and the natural environment? From Genesis to Revelation there is a consistent theme “as goes man, so goes the environment.” The greatest ecological disaster was a consequence of man’s fall. The greatest ecological deliverance so far in history was Noah’s role in salvaging the DNA that made possible the survival of all current air-breathing creatures. The first mentioned covenant (Gen 9) is with animals as well as with man. The cursings and blessings of the Mosaic covenant (Lev 26: Deut. 28) include environmental details as well as socio-political details. When the Son of Man returns and finally judges and blesses, why should we consider it unprecedented for there to be environmental consequences?[37]

Section summary. If liberal theologians uncritically absorbed the high claims of modern scientific cosmology and were seduced by the epistemology of Kant, have some evangelicals similarly imported a Trojan horse of modern language theory into the camp? To formulate hermeneutical rules for interpreting texts of end-time geophysical catastrophes one must exercise especial care in understanding the exodus and subsequent events. To do that one has also to understand what the early chapters of Genesis are saying about man and his physical environment. But one cannot do that if he or she is already convinced that Genesis and Exodus are only Hebrew religious autobiography.

And one cannot break out of the supposed limits of the Hebrew community’s language without relying upon the supernatural origin and design of language given in early Genesis. Indeed, it seems the dog is chasing his tail here (to use a metaphorical expression).

Without a better view of language than that afforded by recent secular theories (that are largely based on Darwinism and Kantian epistemology), interpreters appear to be left with language too limited to carry the full throughput of special revelation. As an example the above discussion has just shown how following the minimalist interpretation of cosmic imagery truncates the theology of the man-nature symbiotic relationship.

A biblically-based model of the language of end-time geophysical catastrophes

Allow me to suggest some places in the Bible to look for information that ought to be used to revise secular models of language before we uncritically rely upon them for informing our hermeneutic. Obviously, in the following discussion I am assuming the validity of traditional historical-grammatical exegesis as the starting point.[38]

The foundation of biblical cosmology.

For the sake of argument, let’s reject the two centuries’ old accommodationist trend in evangelical theology in the interpretation of early Genesis.[39] Following the lead of Whitcomb and Morris let’s participate in what evangelicals like Mark Noll call “the scandal of the evangelical mind.”[40] One simply cannot escape the numerous biblical notices of an anti-modern cosmology by a piecemeal harmonization approach. Interpreting Genesis 1 as a “literary framework” or the flood narrative as one of several Mesopotamian river overflows doesn’t solve the problem. What about the notices of human lifespans before and after the flood (particularly the obvious exponential decay pattern in Genesis 11)? What about the long day of Joshua (Josh.10:12-14), the floating ax-head of Elisha (2 Kings 6:6), the instantaneous destruction of the Assyrian army (2 Kings 19:35), and Hezekiah’s sundial going backward (2 Kings 20:9-11)? What about the miracles and physical resurrection of Jesus Christ? The uniformitarian, placid view of physical reality is challenged again and again in biblical narrative.

What is even more cosmologically challenging is the insistence that there is another realm of creaturely existence, a sort of parallel universe, inhabited by angelic beings and dead humans. Not only does such a realm exist, but there is cause-effect between it and our physical realm. How is one to interpret the religious interference into the northern kingdom of Israel in Ahab’s day from a divine council meeting in this other realm (1 Kings 22:19-23)? Even Gunkel saw that biblical cosmology locates the cause of geophysical phenomenon outside of this world.[41] Starting from this view of reality, then, there is no apriori reason to discount extra-natural phenomena in the biblical text as mere figures of speech.

Contributions of biblical cosmology to a model of language.

We can only briefly survey the wealth of information available in the Bible about the nature of language. Starting with language in the Godhead, it seems clear that there is intra-Trinity language (see the speech in Gen. 1:26 and John 17 with the comment by John in 1 John 1:1-3). This archetype of human language denies all materialist notions of language being sourced in the physical brain.[42]

In Genesis 1 God linguistically creates the components of the physical universe in the fully-functioning form that we humans will later perceive and name.[43] After creating them, he names them. Since both of these acts are acts of divine condescension, we already have language established on the creaturely level that is sufficient to understand reality for the purposes of God’s creation of man.[44] This assertion demands a rethinking of what the “limitations” of language are since language did not originate as Sandy suggests, “in humankind’s fundamental need to communicate.” Human language originated in God’s naming the things he made during Creation Week so that mankind could think God’s thoughts after him.

What about man understanding reality—both material and immaterial through language? From the narratives of Genesis 1 and 2 we observe that God initialized human language with a basic vocabulary. This initialization was required because no human can autonomously begin speaking a language; language can only begin in conversation.[45] Thus armed with a basic vocabulary of his environment given to him in conversation with God Adam could immediately begin the metaphorical development of language of which modern language theory speaks. And he could do so without encountering the subjectivism dilemma of Kantian epistemology. If language indeed determines knowledge for us and if our language is situational—as language theorists seem to be showing—then the Genesis creation story explains how human language can be at once situational and describe the environment “as it really is.” God situates man by design and providence such he can exercise his dominion duty of naming. Thus God’s “choices” for a language of revelation weren’t “limited”; the original language through which all pre-Babel revelation occurred was the very language he taught Adam!

Poetic expression subordinates differences to similarities—similarities that are really there because they are built into the cosmos. The Genesis account reports Adam early on speaking in poetic metaphor as he names his wife, isha, from the noun for man, ish. His metaphor works because although the woman is different, she is similar and related to the man (“bone of my bones. . .taken out of [me]”, Gen. 2:23). These cosmic similarities can crisscross the boundary between the phenomenal world and the largely unseen parallel world of angels and the dead. For example, what the physical serpent did in the garden as a vehicle of Satan is remembered so vividly that Satan is known figuratively forever afterward as the serpent. But we do injustice to Scripture if we stop there, thinking that the “serpent image” of Satan is not what he is really like. The parallel world of spirits has forms and shapes akin to our world. Visions of the angelic beings report that they can have zoological form (e.g., Isa.6:2; Ezk.1:4-28). Since this angelic world was created prior to our world, the forms of our world may well be phenomenal derivatives of spiritual forms.[46] Even man himself is a metaphor—an image of God—in the sense that only the human form is suitable for Incarnation. Metaphors of Yahweh as Warrior (e.g., Isa. 59:16-17) speak of his arm and head. Are these “just” figures of speech? Or are we designed anatomically as well as spiritually in analogy to God?[47] So although language is as Sandy says “limited to what we have experienced,” we must keep in mind that what we have experienced includes God-designed situations revelatory of what he is like. Thus language to describe God doesn’t have to be wholly imaginative.

Any biblical perspective on language must include the effects of the fall. We know from Romans 1:18-23 and the earlier OT prophets that sinful suppression of the knowledge of God inevitably spawns idolatry. Sinful man in his guilt fears God and so imagines a make-believe world that is safe for sinners (i.e., free of the consequences of sin). In so doing, however, he must break the metaphorical chain of language development that began with the original vocabulary given Adam in the garden. Instead of God’s initializing Word of certainty, he tries to substitute his rebellious mind as the originator of metaphor. We can see where that effort ultimately leads by looking at the work of Kant and those following. The 20th century “pure poets” tried to conjure up metaphor with random juxtaposition of words, and postmodernists now live in uneasy tension with the relativistic implications.

Continuing our biblical journey, we come to the Babel judgment upon language. Here we encounter the first appearance of multiple socio-linguistic communities all of which continue the post-fall language perversion in their local historical situations. But the Bible assures us that God remains the ultimate “situator” as he providentially engineers the space-time existence of such socio-linguistic communities so as to preserve a minimal seeking after him (Acts 17:26-27). Evidence of the biblical language story is found in the high complexity of supposedly “primitive” speech,[48] the prevalence of pictographs in old languages,[49] and the occurrence of Genesis 1-9 material fragments across many socio-linguistic communities.[50]

Finally, we come to the creation of a special socio-linguistic community, Israel, through which God has spoken to mankind.[51] (Dispensationalists have always emphasized God’s work through the nation Israel, not just through the believing remnant.) His unique work through this nation ought to sharpen our understanding of appropriate hermeneutics for interpreting judgment and blessing texts. All such texts expound Yahweh’s relationship to Israel, and that relationship is controlled by covenants. “Covenant” is another word for “contract.” People enter into contracts with each other to stabilize relationships and to build trust. Every culture has its own manner of entering into contractual relationships, but their contracts always have the same essentials: definition of the parties to the contract, codification of expected behavior, some sort of enforcement criteria, and an enduring record of the contract.[52] Two hermeneutical implications follow: (1) the meaning of the contract’s terminology must be conserved for the duration of the contract from origin to fulfillment; and (2) only literal meanings can be verified or falsified against the enforcement criteria.

Section Summary. I’ve argued that we must break free from na”¢ve faith in modern cosmology and anthropocentric epistemology. And in this section we hopefully have unearthed enough credible information regarding language origin and capabilities to avoid unintentional contamination from modern language theories on the hermeneutics of cosmic catastrophe texts.

Conclusion: Hermeneutical helps for interpreting end-time catastrophes.

An important dialog occurred at the Dispensational Study Group of the Evangelical Theological Society meeting in 2007 between Brent Sandy (a proponent of reshaping the hermeneutics of prophetic literature to correct traditional dispensationalism) and Mike Stallard (an advocate of traditional dispensational who acknowledges that true doctrinal development can grow with spiritual maturity). [53] Although Stallard agrees with Sandy that we must be careful to discover and respect metaphors, he rightly cautions against the lowered capability of figurative interpretation to discern meaning. Knowing the big idea of a passage, its purpose, and perhaps its genre is important, but one cannot obtain these truths without first working upward from the textual details. It’s the details that give meaning to the overall and keep it from becoming a vague generalization.[54] Stallard’s warning applies in particular to the hermeneutics of uncertainty regarding cosmic catastrophe. Prophecies of terrestrial and extra-terrestrial phenomena, both judgmental and redemptive, were given within a special socio-linguistic community created for the very purpose of special revelation. Due to God’s sovereign conditioning of Israel we can infer some hermeneutical helps for our subject matter.

1. Texts like Matthew 24:21-29 and Revelation 6:12-14 that so reflect OT prophetic passages have to be interpreted in a community context that included pre-Abrahamic texts containing the only true depiction of cosmogony and cosmology. We ought not, therefore, to think that external pagan cosmology sources, whether ancient or modern, are necessary to understand the meaning of the Bible on these matters—helpful, perhaps; necessary, no. Certainly Peter viewed the end-time with cosmic language derived from these pre-Abrahamic source materials that saw the flood not only as global but as an event that changed the entire cosmos (2 Pet. 3:5-7). The prophets spoke from within that perspective so either their view of the world is literally true (being informed from an unbroken chain of linguistic development from the Garden of Eden experience forward and protected by God’s conditioning), or it is an intriguing autobiography of their subjective creativity (being informed according to prevailing language theory from unremarkable conditioning).

2. Texts like Habakkuk 3 obviously remember the exodus event with cosmic imagery. The imagery of geophysical and astronomical instruments of judgment against Egypt (as well as Canaan) should be taken literally. There is no prima facie reason to interpret descriptions of the exodus plagues—especially the day of darkness (Ex. 10:21-23) figuratively.[55] Undoubtedly figurative language accompanies this kind of text. Yahweh’s actions are metaphorically linked to human weaponry (Hab.3:8-9). Egypt at the time of the exodus is depicted as an evil monster (Pss.74:12-15; 87:4; Isa.30:7). But the figurative language is used to link the socio-political situation to parallel history of the unseen universe just as the King of Tyre is linked to Satan in Ezekiel 28. There is a hermeneutical precedent here: literal interpretation of the phenomena itself; figurative interpretation of the unseen spiritual agents involved.

3. Interpretation of judgment and blessing texts for Israel must consider them as exercise of enforcement criteria within the Mosaic Covenant/Contract (Lev.26; Deut.28). Israel’s subsequent history under this special contractual relationship with God established and then reinforced the community’s understanding of judgment and blessing. The prophets centuries later would appeal to the contract’s original witnesses (cf. Deut.32:1; Isa.1:2; Mic.6:1-2). Just as the prophets linked Israel’s infractions to the contract stipulations, so the resulting judgments were seen as consequences of contract violations. Sandy is correct in noting that there is variation between prophetically-threatened judgments and available evidence of fulfillment, but the judgments were nonetheless literal. (How else can a contractual relationship be validated, and how do we know for sure that the threatened judgments have fully come to pass?) One must be cautious in accepting the hermeneutical implications of saying with Sandy and others that the language of curses and blessings “originated” in ancient Near Eastern culture. Pagan analogies to biblical covenants were legalistic creations of political convenience and were not enforceable through nature. Their expressions of judgment, therefore, were laced with hyperbole.

4. a. Hermeneutics of end-time judgments and re-creation in the so-called apocalyptic texts need to be reviewed in at least three regards. First, I question the knee-jerk reaction to interpret figuratively every numerical pattern seen in this sort of literature. Terry, for instance, sees the seven-day pattern in Genesis 1 as an “artificial symmetry of structure.” He then compares it to the seven-fold structures in Revelation, observing that “the seven days of the cosmology are no more to be interpreted literally than are the seven trumpets of the Apocalypse. . . .Both these chapters. . .are of the nature of an apocalypse.”[56] But can’t the natural creation of God have symmetry without an artificially imposed one?[57] One doesn’t have to be a Platonist to see real symmetry and numerical patterns all through God’s handiwork from crystals (think of snowflakes) to the widely-occurring Fibonacci ratios (in plants, sea shells, animal reproduction, and planetary periods of rotation) to the optimized 4-letter genetic code arranged in 3-letter words throughout all amino acids. And isn’t the Trinity a numerical structure? One needs more evidence than a mere numerical pattern to conclude there is referent-less figurative language involved.

4. b. A second reconsideration of end-time judgments and re-creation interpretation concerns their universality and scope. End-time judgments include all nations and their environment—both the phenomenal world and the background spiritual powers. These judgments, however, appear to be distinguishable from judgments against Israel under the Mosaic Covenant/Contract. Whereas those against Israel during the theocracy entail the physical heavens only to the extent of determining climatic extremes, judgment against gentile nations seem to have greater scope and finality by incorporating cosmic language reminiscent of the exodus and conquest. When cosmic language is included in judgments affecting Israel, such as in Joel 2, it seems to be the end-time judgment rather than an imminent one under the Mosaic Covenant/Contract. When cosmic language appears in a text, it should be studied with the realization that the exodus and conquest strongly conditioned the Hebrew language of final judgment. Literal interpretation should be used unless it can be shown that there is reference to the unseen powers behind history in this world.

4. c. Finally, interpretation of end-time language of re-creation should proceed with the resurrection and ascension of Jesus Christ in mind. Unlike the utopian pagan eschatology of the various versions of Marxism, biblical eschatology looks for an entire new universe that we already know has begun. The resurrection body of Jesus has the same form as his mortal body with flesh and bones yet is able to transition between this world and the unseen world. It can eat and drink as our bodies do. Yet it is “fixed” forever and cannot die. George Ladd put it this way: “If we may use crude terms to try to describe sublime realities, we might say that a piece of the eschatological resurrection has been split off and planted in the midst of history.”[58] The resurrection of Jesus shows that there will be a literal re-creation in an instant of time of a world remarkably like our own yet permanently locked in a sinless state. It can be described in language based on our experience in this world. There is no need, therefore, for infecting our hermeneutic of end-time prophecy with pagan cosmology, Kantian epistemology, and anthropocentric language theories.

Logic:

1. Both traditional liberal and many contemporary evangelical interpreters of end-time cosmic catastrophism in the Prophets and the Revelation conclude that these texts are figurative expressions not meant to be taken literally.

a. Liberal advocates of the figurative nature of end-time cosmic catastrophe texts build their case primarily upon (1) the radical difference between such geophysical events and the modern scientific consensus of earth history; and (2) a Kantian distinction between religious and scientific truth.

b. Contemporary evangelical advocates of the figurative nature of end-time cosmic catastrophe texts build their case primarily upon recent theories of language.

2. Figurative interpretation based upon the modern scientific consensus, such as that advocated by liberal exegetes, starts with a denial of the biblical story of the cosmos and so must eventuate in denial of the biblical story of the cosmos. Its textual understanding derived from such use of figurative language, therefore, lacks rational justification.

a. The modern scientific consensus of earth history comes from a ubiquitous, theophobic perversion of man’s dominion function that expresses age-old pagan cosmology in scientific dress. It, therefore, has a systematic agenda of falsifying history in order to make man’s environment safe from divine judgment against sin.

b. To base a hermeneutic upon implications of such a consensus cosmology with such an underlying agenda is to jeopardize the authenticity of the resulting interpretations unless it can be shown that the same implications for hermeneutics also follow from a biblically authentic cosmology. Barring that prospect all such interpretations lack a rational basis.

3. Figurative interpretation based upon a Kantian distinction between religious and scientific truth, such as that advocated by liberal exegetes, starts with a denial of the biblical story of the origin and history of man’s thought and language and so must eventuate in arbitrary subjectivism. Its textual understanding derived from such use of figurative language, therefore, lacks usefulness for the daily operation of theocentric faith.

a. The Kantian distinction between religious and scientific truth resulted from the failure of unbelief to find an adequate foundation to replace biblical revelation and is left excluding all genuine knowledge of God from man’s empirical experience.

b. The exclusion of genuine knowledge of God from man’s empirical experience means that whatever religious faith derives from application of a hermeneutic must be anthropocentric, i.e., it must be nothing more than psychological auto-biography irrelevant for a living faith in a known transcendent self-revealing Creator, Judge, and Savior.

4. Figurative interpretation based upon recent theories of language, such as that advocated by many contemporary evangelicals, uncritically accept the language limitations implied by such theories. Its textual understanding derived from such use of figurative language, therefore, lacks full information throughput of available special revelation.

a. Recent theories of language conceptualize meaningful communication as wholly the product of finite man acting in the context of community, a situation unconditioned by God’s created design and providence.

b. A hermeneutic based upon language wholly constructed by such a community dynamic eliminates or at least minimizes communication of information from God to man and weakens, if not ultimately nullifying, the doctrine of special revelation.

5. The hermeneutic for interpreting end-time geophysical judgment texts must be grounded upon a biblically justifiable cosmology and view of human language and information.

a. A biblically justifiable cosmology is one that respects the authoritative information given in special revelation about the origin and history of the cosmos. Recent work in creation studies is becoming more known and offers insight into the religious and philosophical prerequisites for all cosmologies. “Literal” interpretations of geophysical catastrophes can no longer be casually dismissed on the basis of a conflict with allegedly infallible scientific historiography.

b. A biblical view of human language and information is one that respects the authoritative information given in special revelation about itself. Human language is a finite replica of Trinity language and is designed for personal communication of true and useful information from one mind to another and is fully capable of communicating all necessary thoughts from God to man.

6. Development and function of the language of end-time geophysical judgments.

Endnotes

[1] All references are from the New King James Translation unless otherwise noted.

[2] I use the term “figurative language” in the contemporary sense to include not only individual word combinations such as simile, metonymy, personification, etc., but also whole sentence metaphorical expressions and figures of speech.

[3] Gunkel says that Rahab is a mythical personification of the primeval chaos [tehom] and that “The same mythical view of nature is the basis of all of these texts, one in which the sea is seen as opposed to YHWH’s creation but also kept within bounds by YHWH”. See Hermann Gunkel, trans. K. William Whitney Jr, Creation and Chaos in the Primeval Era and the Eschaton: A Religio-Historical Study of Genesis 1 and Revelation 12 (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2006). Translation of original German edition 1895, 44, 46.

[4] Will Christ Come Again? 21 quoted in Russell D. Moore, The Kingdom of Christ: the New Evangelical Perspective (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2004), footnote 293, p.222

[5] Terence E. Fretheim, Interpretation Bible Commentary: Exodus (Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1991), 165.

[6] ibid., 169.

[7] For an excellent introduction to cosmology from the perspective of biblical authority see John Byl, God and Cosmos: A Christian View of Space, Time, and the Universe (Carlisle, PA: The Banner of Truth Trust, 2001). Byl has an earned PhD in astronomy.

[8] Richard Lewontin, NY Rev of Books, Vol. 44, No. 1 January 9, 1997. Lewontin isn’t alone in admitting worldview roles in theory-selection. One of the most philosophically sensitive evolutionary proponents in our time is Michael Ruse who on several occasions has openly acknowledged that the debate between creationism and evolution is over their respective philosophical foundations. In a 1993 address, for example, he startled his evolutionary colleagues by saying that since his appearance in the Arkansas creation trial, “I must confess, in the ten years since. . .I’ve been coming to this kind of position myself [viz., that of Philip Johnson that evolution is metaphysically based]. . .[those in academia] should recognize, both historically and perhaps philosophically, certainly that the science side has certain metaphysical assumptions built in doing science, which—it may not be a good thing to admit in a court of law—but I think that in honesty. . .we should recognize [this].” Cited in Thomas Woodward, Doubts About Darwin: A History of Intelligent Design (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2003),147. Note carefully that both Lewontin and Ruse consistently identify “science” with “naturalism” presumably assuming that creationism jeopardizes rational thought about physical processes.

[9] See discussion in my article, “Dispensational Implications for Universal Historiography and Apologetics,” Chafer Theological Seminary Journal 7 (July-September 2001), 42-51.

[10] Contemporary figurative interpretation of Genesis 1 is motivated by the centuries’ old failure to harmonize the narrative with modern cosmology—nothing else. For example, Bruce K. Waltke admits that the traditional reading of the text “seems to be the plain, normal sense of the passage” but quickly notes the contradiction with historical science over the length and order of events in Genesis 1. See his article, “The First Seven Days,” Christianity Today, 32 (12 August 1988), 45. The flood narrative must be trivialized to avoid conflict with historical geology as Whitcomb and Morris clearly demonstrated in The Genesis Flood (Philadelphia, PA: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., 1961). Whatever sort of interpretation one adopts, literal or figurative, of Genesis 1 must be the same kind of interpretation of Genesis 6-8 (see how the new NIV Archeological Study Bible capitulates to modern cosmology in its discussion of Gen 1 and the flood on pages 14-17). The thorny problem of locating the biblical exodus event in the conventional ancient near eastern chronology must be solved before exegetes can dismiss the event as a local mundane occurrence within a normal physical environment which biblical writers magnified with cosmic descriptions. With dates given for the exodus from the 12th through the 16th centuries, B.C., and uncertainties in Egyptian dynastic order and duration, any credible synchronization seems remote.

[11] I mention later why this “9th commandment” violation applies also to the OT given its covenant structure.

[12] This oft-overlooked truth is at the bottom of the apologetic revolution begun by Whitcomb and Morris’ bombshell book, The Genesis Flood. Instead of joining the parade of apologists trying to harmonize the Bible with historical science, they turned the tables. They began harmonizing historical science to the Bible! Much to the dismay of their critics the “young earth / global flood” model has blossomed as more and more research shows that indeed literal interpretation of early Genesis supplies enough observational data for an increasingly verifiable picture of past history.

[13] Cornelius Van Til, Christian Theistic Ethics (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Theological Seminary), 222-224. Van Til coined the term “legislative logic” to label unbelief’s definition of the “rational”.

[14] Ibid., 249, 250.

[15] Ibid., 221. Astute observers will note that present discussions on evangelical campuses are precisely over whether “certainty” is to be ascribed to the believer’s faith (assurance) or to the knowledge of the object of his faith. Note the paper Bob Wilken presented at the 16th Annual Pre-Trib Study Group, “Postmodernism and Its Impact upon Theological Education” and the more recent essays by Dean Bartholomew at http://www.cedarvillesituation.com.

[16] Milton S. Terry, Biblical Apocalyptics: A Study of the Most Notable Revelations of God and of Christ (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, reprint of 1898 edition), 8. Terry championed much of what today appears in partial and full preterist interpretations.

[17] Ibid, 43. The issue, contra Terry, isn’t whether the Bible is a textbook on anything; clearly it isn’t. The real issue is whether its historical narratives and prophetic utterances authentically report publicly-observable revelation from God or are mere human imagination originating in a noumenal encounter. See discussion in previous section and footnote 12.

[18] Ibid., p 79.

[19] Ibid., p 80.

[20] Ibid., p 100

[21] Ibid., 463.

[22] A Christian former professor of philosophy clearly spelled out the disastrous consequences of Kantian influence. “Whatever [the contemporary theologian] says, it will be sufficiently vague that when I seek to apply all this to the concrete situation, I will find that I am in a position to decide that what is right is exactly what I want to be right.” Noting that liberal churchmen, left adrift from concrete biblical norms and standards that fit the structure of the real world, decide to adopt a standard they like which “typically conforms fairly closely to the thinking of the avant garde of society. . . .Thus, more and more the churches and their leaders espouse the causes of revolution, Marxism, homosexuality, abortionism, and the like. In doing this they are simply practicing what the theory of the theologians has been all along, that in the area of morality, anything goes. . . .anything, that is, except Biblical morality.” He reports, “Over the past few years several ministers and priests have confided to me the necessity of teaching what they do not believe. They must talk about the Incarnation of Christ. But they do not believe it in the sense that their congregations understand.” Douglas K. Erlandson, “Contemporary Continental Philosophy and Modern Culture: A Practical Application o f Van Til’s Apologetics,” Journal of Christian Reconstruction, 10 (1984) 2, 242-243, 246.

[23] I use the term “apocalyptic” only to point to more symbolic biblical texts that appear in contemporary discussion, not as a formal literary genre. I agree with Robert Thomas, Evangelical Hermeneutics: The New Versus the Old (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 2002), 323-328.

[24] D. Brent Sandy, Plowshares & Pruning Hooks: Rethinking the Language of Biblical Prophecy and Apocalyptic (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2002). Dr.Sandy has identified himself as a dispensationalist.

[25] I. A. Richards, The Philosophy of Rhetoric (New York: Oxford University Press, 1936), 93.

[26] Ibid., 130-131.

[27] Philip Wheelwright, Metaphor and Reality (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1967), 51.

[28] Ibid., 79, 85-86.

[29] John Franke, The Character of Theology: A Postconservative Evangelical Approach, (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2005), 23.

[30] Stanley Grenz and John Franke, Beyond Foundationalism (Louisville, KT: Westminster John Knox, 2001), 65.

[31] Richard D. Patterson, “Wonders In The Heavens And On The Earth: Apocalyptic Imagery In The Old Testament,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society Volume 43 (2000).

[32] The parting of the Red Sea is only “somewhat of an anomaly” (p 389); the long day of Josh 10:9-15 was merely an unparalleled thunderstorm that veiled the shining of the sun and moon while dropping hailstones as was the event of Judg 5:20-21 (p 387).

[33] Ibid., 389.

[34] Ibid., 399.

[35] Ibid., 401.

[36] Fretheim, 112.

[37] Minimizers often try to make an indefensible distinction between traumatic natural events on earth (famine, earthquakes, etc.) and those in the heavens (affects on the sun, moon, and stars). They forget, like today’s climate change alarmists, that the earth is intimately linked to its extra-terrestrial environment; the two cannot be isolated one from the other. Interestingly, Hermann Gunkel observed this inconsistency in his day. Speaking of the preterist type of interpretation of the seals in Revelation, he wrote, “Since now [in the contemporaneous exegetical school of interpretation] the famine, the war, and the pestilence of the first seal have to be understood in the proper way and should be taken this way by all modern interpreters, it is improper to shift suddenly to using the allegorical interpretation in regard to the sixth seal.” (p. 147). Elsewhere he challenged allegorizing the angelic agents of judgment as antithetical to Christian religious belief, “If modern exegetes understand the angel of the famine, of the war, etc. as ‘allegorical figures’. . . , they simply reveal that they no longer understand the Judeo-Christian belief that such plagues would be caused by an angel. In reality, the angel of war is an ‘allegorical figure’ just as little as the angel of the abyss (9:11), the angel of fire (14:18), etc.” Gunkel, 147, 342n115. Of course Gunkel labeled these concepts myth, but at least he was consistent in his mythological interpretation.

[38] For an excellent discussion of the merits of traditional historical-grammatical exegesis with detailed interaction with contemporary hermeneutics see Thomas’s work previously cited.

[39] To observe evangelical retreat in the 19th century see John D. Hannah, “Bibliotheca Sacra and Darwinism: An Analysis of the Nineteenth-Century Conflict Between Science and Theology,” Grace Theological Journal 4 (Spring 1983): 37-58.

[40] Mark A. Noll, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1994), 188-20. Noll tries to attribute modern creationism to Seventh-Day Adventism, thus making it a cultic import like anti-dispensationalists try to attribute dispensationalism to supposedly cultic influences on Darby.

[41] See footnote 37.

[42] Christian students of information theory point out that information must be distinguished from its material carriers—whether ink marks, electronic bits, or sound and light waves—and can only arise in a mind. See Werner Gitt, In the Beginning was Information (Green Forest, AR: Master Books, 2006). In this regard note Proverbs 1:23 where word meaning is parallel to spirit transfer (also note the connection between spirit and doctrine in 2 Cor. 11:4 and 1 John 4:1-3). Ideas are productions of minds whether human or otherwise.

[43] In the narrative literally interpreted God doesn’t create the entire heavens and earth in one step but step by step, component by component, revealing that human language will be able to distinguish them through its noun structure. Moreover, we observe that his creative acts necessarily involve fully-functional components (which avoids the foolishness of modern cosmology in trying to bring functioning systems into existence through gradual chance-generation of their constituent pieces).

[44] Acts of divine condescension are those God performs unnecessarily. Scott Oliphant writes, “Given that God is supremely perfect and without need or constraint, to begin to relate himself to that which is limited, constrained, and not perfect [self-existing] is, in sum, to condescend.” Reasons For Faith: Philosophy in the Service of Theology (Phillipsburg, PA: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., 2006), 233.

[45] Observation of ‘feral’ children experimentally confirm this truth. See the fascinating discussion of research that concludes “It is not until a child discovers what is the meaning of his own sound to others, and then deliberately makes that sound with this meaning attached to it, that the child speaks” in Arthur C. Custance, “Who Taught Adam to Speak?” Doorway Papers No. 1, page 3 available at http://www.custance.org. Custance also recounts the story of how the blind, deaf-mutes, Helen Keller and Laura Bridgeman, learned nouns like “water” and immediately “knew” that these name applied to the general class of varied and yet-to-be-experienced instances (abstraction). This is another example of why a “naïve” literal reading of the Genesis narrative provides much more information about reality than a figurative approach.

[46] John Pilkey made an astute observation concerning physical forms in our world: “The whole point of the Creationist-Darwinian debate is whether the leonine form, for example, originated as a perfect idea in the mind of God or as a casual exercise in feline development. . . .The evolutionary philosophy begins to lose its appeal the instant that a mind begins to suspect that certain visible forms have eternal value,” The Origin of Nations (San Diego, CA: Master Book Publishers, 1984), 230.

[47] We are talking here analogically and not, like Mormonism, attributing a pre-incarnate eternal physical body to God! Rather we are saying that God in condescension appears anthropomorphically, not zoomorphically, because that is how he is. The human form is not merely just one of many possible forms that are all equally capable of revealing God; it alone meets the revelatory requirement.

[48] Ralph Linton wrote, “Most of [the so-called primitive languages] are actually more complicated in grammar than the tongues spoken by civilized people” in The Tree of Culture (New York, NY: Alfred Knopf, 1955), 184f. Since the fall linguistic entropy is increasing, contrary to the evolutionary model.

[49] Pictographs are ideally suited to situations of linguistic confusion: witness modern international symbols for rest rooms and vehicular traffic.

[50] I refer to the common corpus of special revelation originally available through the flood judgment as the “Noahic Bible”. Surviving remnants are discussed in Don Richardson, Eternity in Their Hearts (Ventura, CA: Regal, 1991). Pictographic evidence within the Chinese language are given in C.H. Kang and E. R. Nelson, The Discovery of Genesis: How the Truths of Genesis Were Found Hidden in the Chinese Language (St. Louis, MO: Concordia Publishing House, 1979).

[51] Some have made the intriguing suggestion that the Semitic proto-Hebrew language may well have been the original language God taught to Adam. If so, then God did not have to select among the post-Babel variants. He merely had to preserve this language stock from decaying beyond its ability to carry ancient revelation.

[52] William F. Albright made the interesting observation concerning such covenants/contracts that “contracts and treaties were common everywhere, but only the Hebrews, as far as we know, make covenants with their gods or God.” Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan: An Historical Analysis of Two Contrasting Faiths (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1968), 108.

[53] D. Brent Sandy, “Plowshares and Pruning Hooks and the Hermeneutics of Dispensationalism”, 26pp, and Mike Stallard, “Response to D. Brent Sandy’s Paper: ‘Plowshares and Pruning Hooks and the Hermeneutics of Dispensationalism,’ 11pp.

[54] Recall the footnote 22 that vagueness is hallmark of Kantian epistemology because it can’t connect mental figures with reality.

[55] Nor is there a reason to ignore the textual notices of their uniqueness (e.g., Ex. 8:18-19; 9:18,24; 10:6) so as to interpret them as phenomena falling within the normal scale of events as Colin J. Humphreys, The Miracles of the Exodus (San Francisco: Harper Collins, 2003). If ever the chronological problems are solved so we could look in the right place among Egyptian records, we may very well discover confirming evidence of these events. For an interesting argument that both the traditional exodus date and the liberal date have mislead the search see David Corson, Israel’s Historical Chronology: Its Merit, Precision, Extent, and Implications (Portland, OR: private printing, 2000), available from the author, 3125 N. Farragut St., Portland, OR 97217.

[56] Terry, 43,44,49.

[57] Again we see a Kantian-type epistemology where whatever order exists has to be supplied by man.

[58] George Eldon Ladd, A Theology of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1974) 326.