Relevance of Hebrews to the Modern Reader

I once asked my great aunt, the Jewish missionary, Hilda Koser, to list what she considered to be the indispensable books of the New Testament, without which inclusion our theology and understanding of our faith would be deficient. Within the New Testament, my assumption was that one synoptic gospel along with the gospel of John and a fistful of Pauline epistles would be more than sufficient for establishing orthodox faith and practice. In my estimation, of course, Hebrews would be included in the shortlist of least essential books. Having struggled with the author of Hebrews’ complexity of expression, I could confidently affirm the book’s less than scintillating nature.

Imagine my surprise when my aunt expressed her opinion that perhaps the one indispensable New Testament book was the epistle to the Hebrews! ...

The Use of Old Testament Messianic Themes within the Book of Hebrews

© Steven Charles Ger

Sojourner Ministries

www.sojournerministries.com

Relevance of Hebrews to the Modern Reader

I once asked my great aunt, the Jewish missionary, Hilda Koser, to list what she considered to be the indispensable books of the New Testament, without which inclusion our theology and understanding of our faith would be deficient. Within the New Testament, my assumption was that one synoptic gospel along with the gospel of John and a fistful of Pauline epistles would be more than sufficient for establishing orthodox faith and practice. In my estimation, of course, Hebrews would be included in the shortlist of least essential books. Having struggled with the author of Hebrews’ complexity of expression, I could confidently affirm the book’s less than scintillating nature.

Imagine my surprise when my aunt expressed her opinion that perhaps the one indispensable New Testament book was the epistle to the Hebrews! It is only within this book, she reasoned, that the New Testament reveals with great depth and vivid imagery the present work of our Messiah as perfect high priest, his fulfillment of Yom Kippur, the Levitical Day of Atonement, the Melchizedekian priesthood and the necessity of the New Covenant. Nothing non-essential there for believers, Jewish or Gentile. It was not the book of Hebrews that was dull; it was, rather, my own understanding. My own density, not the text's density, was the problem.

The salvific colors and messianic hues painted by Hebrews’ anonymous master wordsmith alternately shade, brighten and intensify in relation to the spiritual maturity of the reader. Not for the faint of heart is this epistle. Hebrews demands attentive, conscientious study but yields rich theological rewards for those who diligently apply themselves. Together with Romans, it is no overstatement to claim that it ranks as the greatest of the epistles.

Many believers have the perception that the book of Hebrews is confusing; indeed, its reputation for impenetrability extends beyond the layman and even to the clergy. To the modern reader, the density of the author’s argument and the complexity of his rhetorical style have caused many to avoid this singular epistle. Even the title is off-putting to those who are not Jewish themselves, although interestingly enough, the corresponding argument is never made that non-Greeks might struggle with Paul’s letter to the Philippians or non-Italians with Romans.

This perception of comprehensive difficulty causes many believers to choose to skip rapidly through the book in their time of personal Bible study. They are frustrated at the author’s statements to the effect that his arguments are “evident” (7:14) and clear (7:15). Perhaps two thousand years ago on the other side of the world, to people with a deep familiarity with the Old Testament text and who were comfortable with and knowledgeable about animal sacrifice, the arguments within Hebrews were evident and clear, but it is not usually the case for the current generation approaching the text. Today’s readers may choose to energetically bound across worrisome warning passages and enthusiastically vault completely over unfamiliar Old Testament quotations, perhaps allowing themselves to pause only momentarily upon recognition of a reassuringly familiar and easily digestible passage such as chapter eleven’s discussion of faith. This paper is especially written with just such an uncomfortable, apprehensive student in mind (and you know who you are!)

An additional area in which Hebrews can prove instructive concerns the contemporary messianic movement. It is exciting to witness so many Jewish people (which, of course, includes my family) continue to come to faith in their Messiah. However, it is less exciting to observe that many of today’s Jewish believers lack a well-developed, Biblically accurate theology. While there has never been a period of church history devoid of Jewish believers, the modern messianic movement is relatively young, gaining real traction in the second half of the twentieth century and continuing to build. As such, the variety of theological convictions one can detect within the movement run the gamut, broadly ranging “from soup to nuts” (with an occasional strong emphasis on nuts).

A portion of the messianic movement is theologically misinformed to some degree and, unfortunately, is zealously disseminating that misinformation and enthusiastically sharing their errors. The problem areas generally include failure to acknowledge the complete replacement of the Mosaic Covenant with the New Covenant (8:1-13) and failure to acknowledge the complete abolition of the Levitical priesthood in favor of Jesus’ Melchizedekian priesthood (4:14-5:10; 7:11-28; 9:1-10), as well as the consequent abrogation of the Torah in favor of the Law of Messiah (7:12, 19, 28; 10:1). In addition, a small minority are even confused regarding the deity of Jesus. The solution to each of these troubling issues is a thorough grounding in the teachings of the book of Hebrews.

Hebrews reveals the challenge of discipleship, teaching us that our spiritual maturity only develops through the endurance of attendant suffering (12:4-11). Certainly, to bear Christ’s reproach (13:13) and to endure divine education in the school of hard, abusive and shameful knocks for the sake of our spiritual development (12:7) is not the sort of “feel good” message one often hears emphasized today. The proverbial slogan, “no pain, no gain,” while a well-accepted philosophy when articulated within the walls of gym and stadium, is not a particularly popular or well-received theological message in either pulpit or pew. We generally prefer that our yokes be predominantly easy and our burdens especially light.

The Use of the Old Testament in Hebrews

The book of Hebrews is a New Testament masterclass on the profound integration of a pastoral, practical message with messianic prophecy. The Hebrew Bible’s messianic prophecies are not discussed, expounded upon or explained within the text, rather, the messianic prophecies are assumed.

The author of Hebrews’ entire argument rests upon the Old Testament scriptures. The challenge for both the commentator and the student of the book is to recognize that the Old Testament is not the basis of the author’s argument; rather, the Old Testament is his argument. Hebrews is not a book that contains Old Testament scriptural quotations to bolster and support the author’s line of reasoning. On the contrary, this book actually inseparably weaves the Old Testament directly into the book’s fabric from start to finish.

The Biblical quotations, allusions and references fly fast and furiously at the reader throughout the text. As the language utilized within the letter is the actual language of the Old Testament, the author’s argument is accordingly strengthened. There are over thirty explicit quotations, over forty allusions, twenty Hebrew passage summaries, and over a dozen times a biblical name or topic is cited without referring to a specific context.

So robustly integrated is the Old Testament with the argument of Hebrews that any attempt at excision or deconstruction results in forcefully stripping the meat from the bones of this theological banquet and leaving behind a ravaged carcass of literary conjunctions, connectives and one lone personal salutation at the letter’s conclusion. To use an additional culinary metaphor (and your indulgence is most appreciated), the book of Hebrews is like one of those expensive gourmet chocolate chip cookies, so resplendent with embedded chips that it is difficult to separate out the taste of the actual “cookie” component. It is impossible to “bite” into a passage of Hebrews without experiencing the savory taste of the Old Testament.

Of great significance is that while the author inarguably interprets the Old Testament using both a literal and grammatical methodology (in other words, he portrays the events that are recorded within the Hebrew Scripture as actually having happened just the way that they are presented therein), he nonetheless views the Old Testament through a dominant Christological perspective. The author’s major arguments all fundamentally acknowledge the great theme that flows from one extremity of the Hebrew Scriptures to the other, that of the messianic promise. In this, the author is in good company. Throughout the New Testament, the messianic content of the Old Testament is repeatedly brought forth, most often as the razor-sharp instrument through which the gospel is both proclaimed and explained.

With gusto, the author of Hebrews vigorously wrings dry the ancient Scriptures, constraining them in the winepress of his exalted vision and extracting every possible ounce of intrinsic Christology contained within each text. The text of Hebrews becomes a platform upon which, strata by strata, the author develops his theology about Jesus. As he builds his case, each new layer of propositional truth adheres to its neighbors through his slathering a liberal application of Old Testament mortar between every tier, without exception, creating an unassailable tower of Christological, messianic doctrine, assurance, exhortation and encouragement which stands today as resolutely as when the tower was first constructed some two millennia ago.

As Biblically literate Jews (as all Jews were in the first century), the original recipients of Hebrews could be relied upon to supply the original context of the author’s Old Testament quotations, allusions, etc., without having everything spelled out for them. Certainly, if the author needed to provide elaborate contextual backgrounds for every use of the Old Testament, the scroll containing his epistle would have needed super-sizing (this is precisely why chapter eight’s extensive quotation of Jer. 31:31-34 is so unprecedented. However, unlike first century Jewish believers, few twenty-first century believers’ brains function as Biblical concordances; therefore, for the purposes of this paper, certain Old Testament passages will be summarized and discussed as they arise within Hebrews’ argument.

Table 1. Hebrews’ Extensive Use of Messianic Prophecies (predictive, typological, analogical)

|

OT Reference |

Hebrews Reference |

Subject |

|

Gen. 22:1-10 |

11:17 |

The binding of Isaac |

|

Gen. 22:16 |

6:13 |

The binding of Isaac |

|

Gen. 22:17 |

6:14; 11:12 |

The Abrahamic Covenant |

|

Gen. 49:10 |

7:14 |

Prophecy regarding Messiah’s descent from Judah |

|

Ex. 12:21-30 |

11:28 |

The Passover |

|

Ex. 14:21-31 |

11:29 |

The Exodus |

|

Ex. 25:10-22 |

9:4-5 |

The ark of the covenant |

|

Ex. 25:23-26:30 |

9:2 |

The Tabernacle and its components |

|

Ex. 25:40 |

8:5 |

The Tabernacle |

|

Ex. 29:38 |

10:11 |

The Levitical priestly service |

|

Lev. 16:2 |

6:19; 9:7 |

The High Priest’s role on the Day of Atonement |

|

Lev. 16:6-7 |

9:13; 10:4 |

The Day of Atonement |

|

Lev. 16:27 |

13:11 |

The Day of Atonement |

|

Lev. 17:11 |

9:22 |

The necessity of blood for atonement |

|

Lev. 23:27; 25:9 |

10:25 |

The Day of Atonement |

|

Num. 19:9 |

9:13 |

The ashes of the red heifer |

|

Num. 23:19 |

6:18 |

The unchangeable purpose of God |

|

Deut. 18:15-18 |

3:1-6 |

Prophet like Moses |

|

1-2 Sam.; 1 Chron. |

11:32 |

Davidic Covenant |

|

2 Sam. 7:14ff |

1:5 |

Davidic Covenant |

|

1 Chron. 17:13ff |

1:5 |

Davidic Covenant |

|

Ps. 2:7 |

1:5; 5:5 |

The Sonship of the Messiah |

|

Ps. 2:8 |

1:2 |

The Son as heir of creation |

|

Ps. 8:5-7 |

2:6-8 |

The divine authority of the Son |

|

Ps. 22:22 |

2:12 |

The purpose of the Son |

|

Ps. 40:6-8 |

10:5-9 |

The Levitical sacrificial system |

|

Ps. 45:6-7 |

1:8-9 |

Deity of the Son |

|

Ps. 102:25-27 |

1:10-12 |

Deity of the Son |

|

Ps. 110:1 |

1:3, 13; 8:1; 10:12-13; 12:2 |

The divine authority of the Son |

|

Ps. 110:4 |

5:6, 10; 6:20; 7:3, 17, 21 |

The Son’s Melchizedekan Priesthood |

|

Ps. 118:6 |

13:6 |

The promise of God’s abiding presence |

|

Is. 11:1 |

7:14 |

Prophecy regarding Messiah’s descent from Jesse |

|

Is. 53:10-12 |

10:12 |

Isaiah’s suffering servant |

|

Is. 53:12 |

9:28 |

Isaiah’s suffering servant |

|

Jer. 31:31 |

12:24 |

The New Covenant |

|

Jer. 31:31-34 |

8:8-12; 10:16-17 |

The New Covenant |

|

Jer. 32:40 |

13:20 |

The New Covenant |

|

Ezek. 36:25 |

10:22 |

The New Covenant |

|

Ezek. 37:26 |

13:20 |

The New Covenant |

|

Dan. 7:13-14 |

2:6 |

Son of Man |

|

Zech. 9:11 |

13:20 |

The New Covenant |

|

Zech 13:7 |

13:20 |

Prophecy regarding the Messiah’s death |

|

|

|

|

Messianic Theology:

Hebrews provides a full-orbed digest of Jesus’ identity, distinctiveness, accomplishments and ministry within a limited, time-bound, three-part chronological framework. The text relates crucial aspects relating to Jesus’ preexistence, incarnation and exaltation. For example, Jesus is revealed as the Father’s preexistent agent of creation (1:2, an emphasis the author shares with Paul, Rom. 11:36; 1 Cor. 8:6; Col. 1:16). His incarnation is explored in the author’s careful attention to Jesus’ temporarily subordinate status (2:7), His ability to learn obedience through suffering (5:8), His sinless life (4:15) and shameful death (2:14; 9:14, 28; 13:12).

Of course, an especially prominent designation related to this second theme of His deity is Jesus’ identity as God’s Son. He is called simply a or the Son (1:2, 5, 8; 3:6; 5:5, 8; 7:28) and three times the actual phrase Son of God is used (4:14; 6:6; 10:29). As God’s Son, Jesus is the Radiance of God’s Glory (1:3), the Exact Representation of God’s Nature (1:3), the Instrument of Creation (1:2, 10), the Heir of All Things (1:2), the Upholder of All Things (1:3), and the One Whom Angels Worship (1:6). He is the exalted One Who Appears in the Presence of God (9:24); indeed, a key emphasis in Hebrews is that Jesus is the One Who Sits at God’s Right Hand (1:13; 8:1; 10:12-13; 12:2).

In addition, the Son of God’s redemptive role is heavily accented. The One Who was Temporarily Made Lower than the Angels (2:6), Jesus is He Who Sanctifies (2:11), the Obtainer of Eternal Redemption (9:12) and the Source of Eternal Salvation (5:9). As the Firstborn (1:6; 12:23) and Forerunner (6:20), the One Who Temporarily was Made Lower than the Angels (2:7), He became the Inaugurator of a New and Living Way (10:19). This resulted in His status as Victor over the Devil (2:14) and Liberator of the Devil’s Slaves (2:15). The Son of God is the Unchanging One Whose Years Have No End (1:11-12); the Same Yesterday, Today and Forever (13:8).

In recognition of his function as the Aid of the Tempted (2:18), the Helper of Abraham’s Descendents (2:16), a Merciful and Faithful High Priest (2:17), and the High Priest and Apostle of Our Confession (3:1), the author of Hebrews can designate Jesus as the Great Shepherd of the Sheep (13:20).

This particular Priest’s enumerated accomplishments overwhelm and inspire awe. He is the Maker of Purification of Sins (1:4), the One Who has Perfected the Sanctified for All Time (10:14), and the One Able to Save Forever because He is the One Who Lives to Make Intercession (7:25). The Melchizedekian Priest (5:6, 10; 6:20; 7:17) is an Eternal Priest (7:21, 24), a Great Priest Over the House of God (10:21). The One Who Learned Obedience (5:8) through the experience of suffering became the Perfected One (5:9; 7:28).

Remaining themes receive less discussion within the text but no less prominence. Jesus’ identity as perfect sacrifice, Melchizedekian High Priest, and divine Son of God position Him as the ultimate covenant mediator between God and humanity. He is the Mediator of a New Covenant (9:15; 12:24), the Mediator of a Better Covenant (8:6) and most effectively, the Guarantee of a Better Covenant (7:22). Jesus is also called the Author of Salvation (2:10) and the Author and Perfecter of Faith (12:2). Readers are reminded of the Messiah’s second advent through the author’s identification of Jesus as He Who is Coming (10:37) and the One Who Returns for Salvation (9:28). Finally, although Jesus’ preferred self-designation in the gospels, the profoundly messianic title, Son of Man, is only used once (2:6) indirectly, within a quotation from Psalm 8:4.

Purpose

The book of Hebrews is designed to definitively demonstrate the supremacy of Jesus Christ (see Table 1) in both His identity (person) and ministry (priesthood). In the epistle’s central core, the commencement of the eighth chapter, the author straightforwardly reveals the central point of his argument, “Now the main point in what has been said is this: we have such a high priest, who has taken His seat at the right hand of the throne of the Majesty in the heavens, a minister in the sanctuary and in the true tabernacle, which the Lord pitched, not man” (8:1-2).

Table 2. The Supremacy of the Messiah

|

Superior Regarding |

Reference |

|

Prior Prophetic Revelation |

1:1-3 |

|

Angels |

1:4-2:18 |

|

Moses |

3:1-6 |

|

Levitical Priesthood |

4:14-5:10; 7:11-28; 9:1-10 |

|

Abraham |

7:1-10 |

|

The Torah |

7:12, 19, 28; 10:1 |

|

Mosaic Covenant |

8:1-13 |

|

Levitical Sacrifices |

9:11–10:18 |

The entirety of the text’s concern is to establish a doctrinal foundation of Jesus’ supremacy in every area pertaining to God and His divine program: revelation, priesthood, law, hope, human/divine relationship, covenant, promise, sacrifice and sanctuary; and having established this foundation, to then erect upon it a practical and ethical structure upon which the community of faith may suitably apply these doctrinally foundational truths in every situation. Hebrews explains that what God has supplied for His people in this present age is, in all ways, new and superior. God’s provision demands a commensurate response from the faith community.

The complete argument of Hebrews can be broken down as follows:

God’s new and superior revelation (1:1-2)

discloses that with a new and superior permanent priesthood (7:11-19, 28)

necessarily comes a new and superior permanent law (7:11-19, 28),

which yields a new and superior permanent hope (7:18-19)

by which to relate to God (7:25),

Who provides a new and superior permanent guarantee (7:22-24)

of a new and superior permanent covenant (7:22; 8:6-7)

based upon new and superior promises (8:6-7),

established through a new and superior sacrifice (9:23-28)

offered by a new and superior permanent Priest (7:11-8:6)

within a new and superior sanctuary (8:2-5; 9:11-12, 24).

In consideration of the above breakdown, it becomes obvious that the motivating force that undergirds the author’s passionate defense of the Messiah’s superiority is his equally passionate conviction regarding the inferiority of the Mosaic Covenant and the entire Levitical system. One simply cannot demonstrate superiority in a vacuum; in order to demonstrate the essential superiority of one thing, it is compulsory to reveal the essential inferiority of another.

For the author of Hebrews, the Mosaic Covenant is inferior to the New Covenant (7:22; 8:6-7); God’s guarantee of the Mosaic Covenant is inferior to that of the New Covenant (7:22-24); the Mosaic Covenant’s promises are inferior to those of the New Covenant (8:6-7); the Torah is inferior to the law of Messiah (7:11-19, 28); the Aaronic High Priesthood is inferior to the Melchizedekian High Priesthood (7:11-19, 28); the Levitical High Priests are inferior to the Messiah (7:11-8:6); the Levitical system’s sacrifices are inferior to the Messiah’s sacrifice (9:23-28); the Tabernacle/Temple is inferior to the Messiah’s heavenly sanctuary (8:2-5; 9:11-12, 24); the hope incited through the Levitical system is inferior to the hope through the Messiah (7:18-19); the way to relate to God through the Levitical system is inferior to the Messiah’s new means (7:25); the supernatural mediators of the Torah, angels, are infer to the Messiah in both identity and ministry (1:4-2:18); the human mediator of the Torah, Moses, is inferior to the Messiah in both identity and ministry (3:1-6); Abraham, the Jewish national father, is inferior to the Messiah (7:1-10); and all prior prophetic revelation is inferior to God’s new revelation in His Son (1:1-2). Two thousand years later, the argument of Hebrews’ stunning indictment of first century Judaism’s inadequacy in light of Jesus’ superiority still possesses the power to astonish.

However, the author of Hebrews never demeans Judaism. The student of Scripture must always bear in mind that the author’s indictment of Judaism, the Mosaic Covenant and the Levitical system is only germane when in comparison with the Messiah’s eminence. No one belittles the moon for the limited quantity of light it provides from the night sky; in the absence of a superior heavenly body, the moon does a tremendous job, and when the moon remains hidden, its light is sorely missed.

However, when both moon and sun share the same sky and can be directly compared, no one would prefer the moon’s output in lumens over the sun’s. In the light of day, one heavenly body is so obviously superior to the other that it then becomes obvious that although they both emit light, their quality is so different that they really cannot be compared. The author of Hebrews is simply pointing out that the intrinsic glory of God’s Messiah is superior to the reflected glory of the Mosaic Levitical system.

With the author’s stated purpose established, that of definitively demonstrating the supremacy of Jesus Christ in both His identity (His person) and ministry (His priesthood), we must discover the likely event, issue or concern that prompted the author to expend the effort of placing ink to parchment.

The Jewish Christian recipients of Hebrews had previously undergone a brutal season of persecution (10:32–34) and were now menaced by its imminent resumption and perhaps, intensification (12:4). The community was most likely situated in the holy city of Jerusalem or, alternatively, the nearby environs of Judea, and it is not hard to imagine the pressure of living among a general populace that had grown progressively hostile toward the church over the past two decades. It had been quite some time since the church had found notable favor with the residents of Jerusalem (Acts 6:7; 9:31). The Jerusalem of the first century’s seventh decade was a volatile place to call home.

One can surmise from the author’s topical emphases that a portion of the community was in the process of considering a renunciation of their messianic faith for the purpose of alleviating the tension and escalating pressure of living under threatened or actual persecution. The duration of their intended hiatus from their faith commitment to Christianity is unclear, perhaps it was only temporarily, until the storm cloud of threatened persecution had passed from sight.

Their thinking about the status of their salvation may have been similar to those who have, at one time or another, not paid our premiums and allowed our insurance policies to lapse. Most insurance policies have what is called a “grace period” (appropriately enough), when, although the policy is currently in arrears, the insurance company will still honor their prior commitment. If we allow the grace period to pass without paying our outstanding balance, then the policy lapses. Yet most of the time, all we need do is pay our premium once again and the policy is promptly renewed. These Jewish Christians contemplated a temporary lapse in their salvation insurance which they could promptly renew when it was more convenient to stand for Jesus.

Alternatively, the clues within the text leave open the possibility that what was being contemplated was no timid renunciation of Christ born of fear, but the defiant act of rebellion by a spiritually immature (5:11; 6:12), insecure, and frustrated group who had had enough of taking heat for their hope in the Messiah (2:3, 18; 3:6, 12–15; 4:1, 11, 14; 6:4–6, 9–12; 10:19–29, 35–39; 12:1–3, 14–17, 25; 13:9, 13). Whether the community was timid or bold in their contemplation of spiritual mutiny, the author of Hebrews makes every attempt to persuade them not to press forward with this ill-conceived strategy.

Messianic Themes

To the modern reader, the structure of Hebrews is cumbersome; the author’s method of presentation, unfamiliar; and his argument, often confusing. His dizzying methodology, on exhibition throughout the book’s entirety, of briefly introducing a subject and then completely dropping the newly introduced subject in favor of a topic already discussed, then returning to the subject he had introduced, developing it for a while and then dropping it again to introduce a new topic, can be intensely disconcerting. Assurance of subject matter comprehension poses a challenge. Frustration sets in, together with a longing for someone to iron out the multiple creases and curves within the text’s argument; for an author who writes straightforwardly without continuously backtracking over previous material.

However, Hebrews is a book that rewards multiple readings. Only upon multiple readings can one derive an overview and a sense of what can only be called the book’s “rhythm.” For this commentator, it is the concept of rhythm, along with musical concepts such as point and counterpoint, harmony and dissonance that provided a key to finally seeing Hebrews’ “big picture.” While Hebrews does indeed progress along a straight line with a definite structure of beginning, middle and end, it does so with style and attitude. The author takes his time, methodically laying the groundwork for each new theme, intermittently revisiting and, eventually, fully developing them. Occasionally a theme is treated separately, but generally the themes are played in tandem, layered one on top of another in point and counterpoint.

These layered themes usually play together harmoniously, but now and then create dissonance, the absence of harmony. Most people instinctively reject dissonant music. The absence of harmony simply “hurts their ears” and they cease to listen. That is why a great many people do not like jazz, because it is musical style chock full of dissonance.

Many readers treat the book of Hebrews like an album of jazz music that we originally purchased because we liked one particular song. They reject Hebrews’ singular style in favor of more easily digested and absorbed New Testament works. Although since the album is already in their collection, they may, from time to time, take it out, play a favorite selection or two (chapter 11’s “Hall of Faith, for example) and then turn it off before having to listen to the remainder. Nonetheless, we should not treat Hebrews like an album that we are proud to have in our collection but to which we no longer listen. Reading the whole word of God is not really an optional activity.

Nor should the word of God be like having to eat your vegetables, knowing that you need the nutrients but never enjoying the process. Vegetables are funny things. Many a child commences his culinary journey with a deep aversion to certain vegetables (Brussels sprouts, for example), and only consumes them upon the instigation of his parents. However, as the child matures, his palate may mature as well, becoming more sophisticated with gastronomic experience, and Brussels sprouts might well become a favorite (unlikely, but nonetheless possible).

Music is like that, too. Some types of music are difficult to enjoy upon first hearing (for example, jazz and opera, or for musical theater fans, the collected works of Stephen Sondheim). However, if one would purposefully endeavor to understand these less accessible types of music, he may well find the development of appreciation upon repeated listenings as his ear matures. Likewise, the author of Hebrews has a great deal to say concerning spiritual maturity and development (5:11-6:2), and his concerns may be most favorably appreciated by the reader who diligently applies himself to a study of his argument.

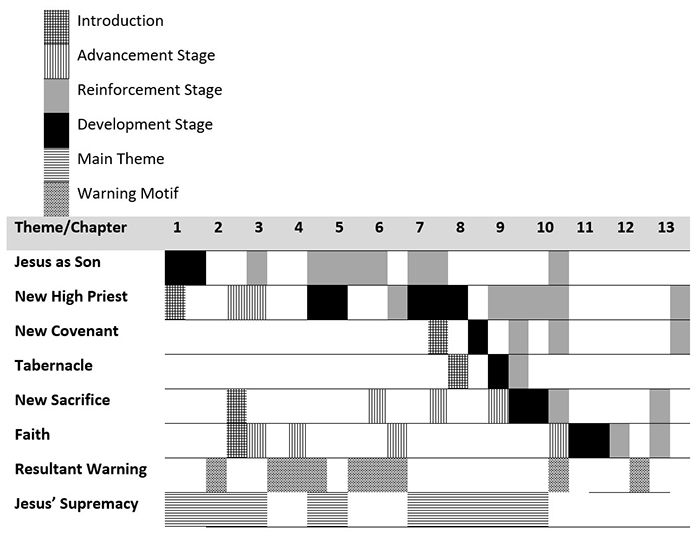

While there is a variety of opinion as to exactly how many themes are contained within the text of Hebrews, this paper sees one main theme and six underlying themes of support. The main theme is, of course, the absolute Supremacy of Jesus (1:1-3; 1:4-3: 6; 4:14-5:10; 7:1–10:18). The six supporting themes are Jesus as Son (1:2; 1:3-12, 3:6; 4:14; 5:5-10; 6:6; 7:3; 7:28; 10:29); the New High Priest (1:3; 2:17-3:1; 4:14-5:10; 6:19-8:6; 9:11-12; 9:24-25; 10:11-14; 10:21-22; 13:20); the New Covenant (7:18-22; 8:6-13; 9:15-18; 10:15-18; 10:29; 13:20); the Tabernacle (8:2-5; 9:1-10; 9:19-24); the New Sacrifice (2:9-15; 6:6; 7:27; 9:11-10:22; 10:29; 13:11-13); and Faith (2:17; 3:2; 3:5; 4:2; 6:12; 10:22-23; 10:38-39; 11:1-12:2; 13:7).

Table 3. Progressive Advancement of Hebrews’ Supporting Sub-Themes

|

Theme |

Jesus as Son |

New High Priest |

New Covenant |

Tabernacle |

New Sacrifice |

Faith |

|

Introduced |

1:2 |

1:3 |

7:18-22 |

8:2-5 |

2:9-15 |

2:17 |

|

Advanced |

|

2:17-3:1 |

|

|

6:6 |

3:2 |

|

Advanced |

|

|

|

|

7:27 |

3:5 |

|

Advanced |

|

|

|

|

|

4:2 |

|

Advanced |

|

|

|

|

|

6:12 |

|

Advanced |

|

|

|

|

|

10:22-23 |

|

Advanced |

|

|

|

|

|

10:38-39 |

|

Developed |

1:3-12 |

4:14-5:10 |

8:6-13 |

9:1-10 |

9:11-10:22 |

11:1-12:2 |

|

Developed |

|

6:19-8:6 |

|

|

|

|

|

Reinforced |

3:6 |

9:11-12 |

9:15-18 |

9:19-24 |

10:29 |

13:7 |

|

Reinforced |

4:14 |

9:24-25 |

10:15-18 |

|

13:11-13 |

|

|

Reinforced |

5:5-10 |

10:11-14 |

10:29 |

|

|

|

|

Reinforced |

6:6 |

10:21-22 |

13:20 |

|

|

|

|

Reinforced |

7:3 |

13:20 |

|

|

|

|

|

Reinforced |

7:28 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reinforced |

10:29 |

|

|

|

|

|

The author’s technique in his use of these six supporting themes follows a basic pattern. There are usually four distinct stages to each supporting theme: introduction, advancement, development, and reinforcement (three themes, those of Sonship, New Covenant and Tabernacle, skip the advancement stage). The first thematic stage, introduction, briefly introduces a theme, providing a teaser or hint of the topic to come, after which the theme is usually temporarily abandoned in favor of engaging some stage of the subsequent theme.

The second thematic stage, advancement, begins when the theme in question is again picked up, perhaps slightly advanced and fleshed out, but then, once again, full development is deferred and the theme is exchanged in favor of yet another. Eventually, within this series of introducing, hinting, advancing and intermingling, the author brings each theme to its third stage, that of development. In this thematic stage, the author finally gets to his point, presenting the crux of his topical argument. Once fully developed in the third stage, each theme reaches the fourth stage, that of reinforcement. This is where each theme receives a series of brief echoes, or reprises, throughout the remainder of the piece.

The genius of Hebrews is that the author weaves these themes together, intermingling the stages of introductions, advancements, developments, and reinforcements, as he simultaneously treats varying stages of each theme. An additional layer is added whenever the main “Supremacy” theme also resonates, which is often.

A final tier is added by the five warning passages strategically strewn throughout the book. As in a Wagnerian opera (or, alternatively, a Star Wars movie), these warning passages are leitmotifs, expressly designed to punctuate the theological music. They sound a dark, ominous motif that calls us back to the author’s symphonic themes, lest our attention has wandered.

The inherent complexity of this process may be visualized by imagining yourself as singing all three round parts of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” while standing upside down on your head, accompanying yourself by blowing a kazoo through your nose and keeping rhythm by clanging together the cymbals affixed to your knees.

In the following section, utilizing the provided charts, let us now embark on a brief guided journey through the glorious thematic structure of this tour de force.

Throughout the text of Hebrews, the main theme and the six supporting themes are symphonically interwoven with profound dexterity. This symphonic metaphor is especially applicable in the author’s opening words. No common, simple epistolary greeting will suffice to introduce this author’s grand theme. With the startling intensity of the opening measures of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, he skillfully grabs hold of his reader’s attention in the first three breathtaking verses by announcing the definitive supremacy of Jesus. This majestic main theme will underscore the remainder of the piece.

Such is the author’s artistic mastery within the first chapter that in conjunction with the main theme, he is simultaneously introducing his first two supporting themes, that of the Sonship of Jesus and the New High Priesthood (see Table 4). As the main Supremacy theme continues, the briefly introduced New High Priesthood theme is dropped, and the Sonship theme, skipping over the advancement stage, flows directly into the third stage, that of development.

Just as chapter two commences, we are briefly introduced to the initial dark, ominous tones of the warning passages. They pass quickly away, yielding to other themes. Within chapters two and three we find the Sonship of Jesus theme in the reinforcement stage, the New High Priesthood theme in the advancement stage, as well as the introduction of two new themes, that of the New Sacrifice and Faith. Faith enters the second stage, that of advancement. The main Supremacy theme continues from chapter two through the center of chapter three, at which point it rests and the dark, ominous notes of warning sound again, continuing through chapter four.

Chapters four through six again find the Sonship of Jesus theme in the reinforcement stage, both the New Sacrifice and Faith Themes in the advancement stage, and the New High Priesthood Theme in a “double” development stage. So important is this particular supporting theme that it alone warrants two separate stages of development (4:14-5:10; 6:19-8:6). Although briefly pausing in chapter five, the dark warning motif dominates this section.

Chapter seven introduces a new supporting theme, the New Covenant. The Sonship theme is in the reinforcement stage. The New Sacrifice theme is in the advancement stage. The New High Priesthood theme continues in its second development stage. The author again picks up the main Supremacy theme throughout the chapter. The Faith theme rests through chapter seven.

Chapter eight introduces the final supporting theme, that of the Tabernacle. In the development stage is the New Covenant theme, as is the New High Priesthood theme. The main Supremacy theme plays throughout chapter eight, and the Sonship, New Sacrifice and Faith themes rest.

In chapters nine and ten, with no new themes to introduce, the author interweaves all six supporting themes along with the main Supremacy theme. In the advancement stage is the Faith theme. Skipping over the advancement stage and proceeding directly into the development stage are both the Tabernacle and New Sacrifice themes. In the reinforcement stage are the Sonship, New High Priesthood, and New Covenant themes. The main Supremacy theme sounds its final note midway through chapter ten, overtaken by the dark, ominous warning motif.

Analyzing the graphical chart, it is easy to see that the past four chapters, seven through ten, provide the heart of the author’s masterpiece. Every major and minor theme, along with the warning motif, is heard at some point in this section, often simultaneously. To some readers this might seem a cacophony while to others, it represents a theological smorgasbord. This central section is the eye of the storm, where the author fully develops four of his six supporting themes like stair steps, one advancing upon another, all the while sounding the main theme of the Messiah’s Supremacy. The author has demonstrated his proficiency in building every theme to an appropriate climactic crescendo in the very heart of the book. The author’s first century rhetorical style demands that for maximum effectiveness, he build not to a “big finale,” the rousing conclusion, but rather to place the stirring climax, the very heart of his argument, within the physical center of the book.

The author startles us with chapters eleven and twelve, arresting our attention. After four complex chapters of theme swirling upon theme, layer upon layer, he silences all but one theme, that of Faith, which finally enters the development stage, the last theme to do so. The simple, focused hush of that chapter’s contents provides a much-needed opportunity to catch our breath. A final section of warning motif punctuates the last section of chapter twelve.

In the final chapter, the author concludes his piece by gently restoring only four supporting themes, all now in the reinforcement stage: New High Priesthood, New Covenant, New Sacrifice, and Faith. Thus concluded, the masterpiece is then (hopefully) met by the metaphorical thunderous applause of its readers hastening to apply its message to their lives.

Table 4. Graphical Representation of Hebrews’ Integrated Thematic Development